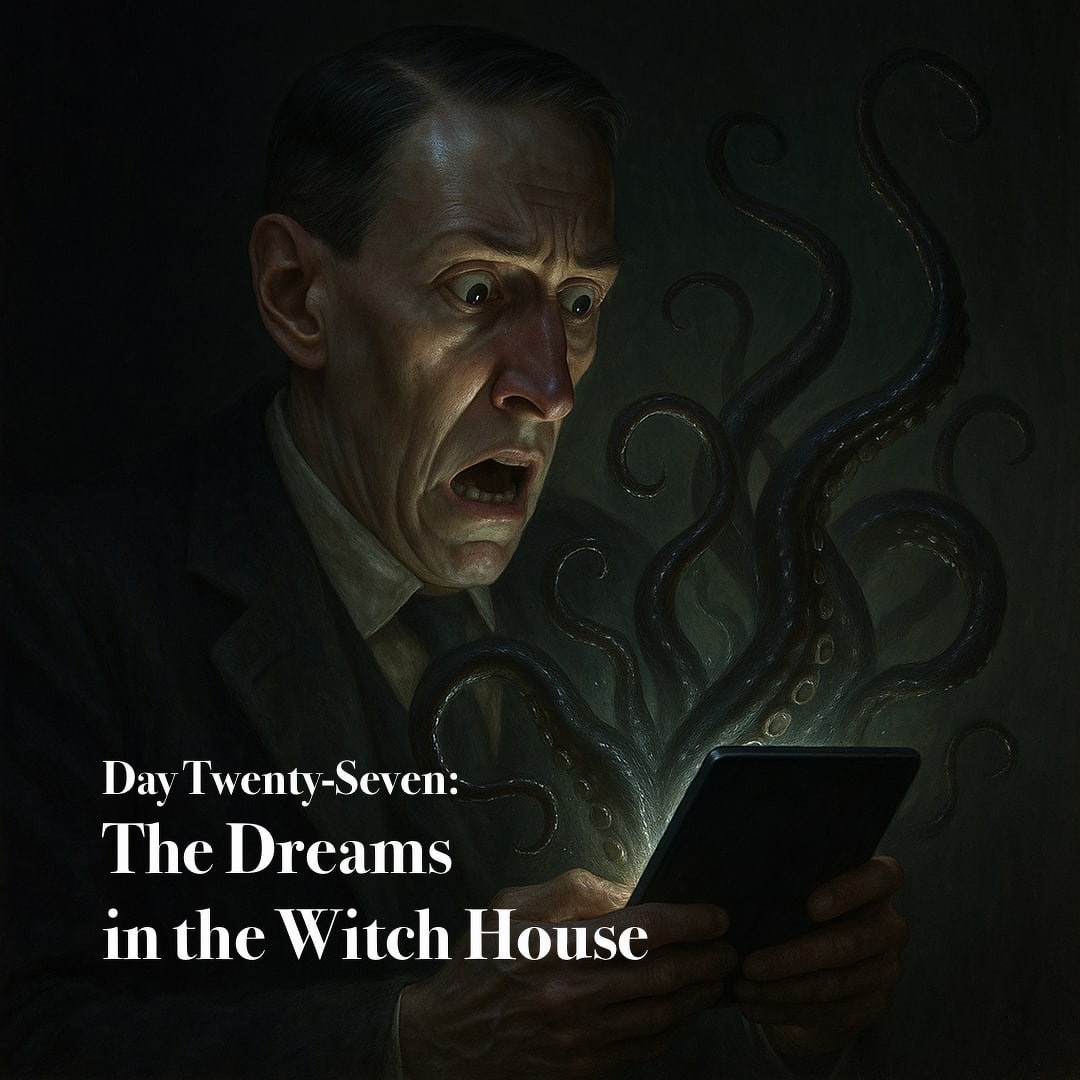

The Dreams in the Witch House

I must confess, when I rekindled my October ritual of reading one tale each eve from the dread canon of H. P. Lovecraft, I did not foresee how the practice might at times curdle into an uncanny toil. Yet duty, once pledged to the eldritch, must be upheld. And so we descend once more into the abyssal lattice of nightmare and geometry, today’s accursed chronicle, “The Dreams in the Witch House”.

“The Dreams in the Witch House”

Walter Gilman, a student of forbidden mathematics and eldritch folklore at that ill-starred institution, Miskatonic University, took lodging in a crooked attic chamber of Arkham’s infamous Witch House, once the lair of Keziah Mason, who had fled mortal justice in the Salem days through secrets no human mind should grasp. The room itself seemed subtly wrong, its angles violating Euclid, hinting at gulfs of space unseen by earthly eyes.

In his fevered nights, Gilman beheld vistas of alien immensities where geometry dissolved into madness, and he walked beside Keziah and her abhorrent familiar, the loathsome Brown Jenkin. Drawn into rites of blasphemy, he bent his trembling will to the commands of Keziah, Jenkin, and the crawling chaos Nyarlathotep, signing the dread Book of Azathoth and aiding in a nameless sacrifice. Blood and revelation commingled, and Gilman’s end came beneath the gnawing fangs of his inhuman tormentor.

When at last the Witch House fell, its shattered beams yielded relics of horror:grim tomes, infant bones, and the long-hidden skeletons of witch and familiar, sealed testimony to terrors beyond all sane conjecture.

In the dim twilight of his creative years, Lovecraft’s “The Dreams in the Witch House” emerged—a tale fraught with strange geometries and spectral dread, only to meet the chill disdain of mortal critics. August Derleth, discerning in its tortured angles some promise of commerce, yet named it a “poor story,” a pronouncement that struck the author’s spirit with mortal gravity. In despair, Lovecraft confessed that his “fictional days are probably over,” and withdrew the work into the abyss of neglect. Yet Derleth, impelled by unseen designs, dispatched it to Weird Tales, where it was accepted by those who traffic in the eldritch and the macabre. When a request came to breathe it into the vulgar airwaves of radio, Lovecraft recoiled, declaring that such “weirdness” would become a lifeless pantomime: “flat, hackneyed, atmosphereless.”

Later generations, as if cursed to echo Derleth’s verdict, called it “a minor effort,” “a magnificent failure,” and “one of his poorest later works.” They spoke of plots without compass, of visions unbound by logic, of imagery more vivid than the reason that should have tethered it. Yet in the turning of cosmic cycles, new voices arose to sanctify the tale. Kenneth Hite beheld within it the purest strain of Lovecraftian cosmicism, the dreadful music of From Beyond made manifest. And Michel Houellebecq, in dark reverence, placed it among the “definitive circle”—those dread scriptures which form the pulsing heart of the Mythos, wherein humanity glimpses, for an instant, the cold geometry of eternity.