The Shadow Over Innsmouth

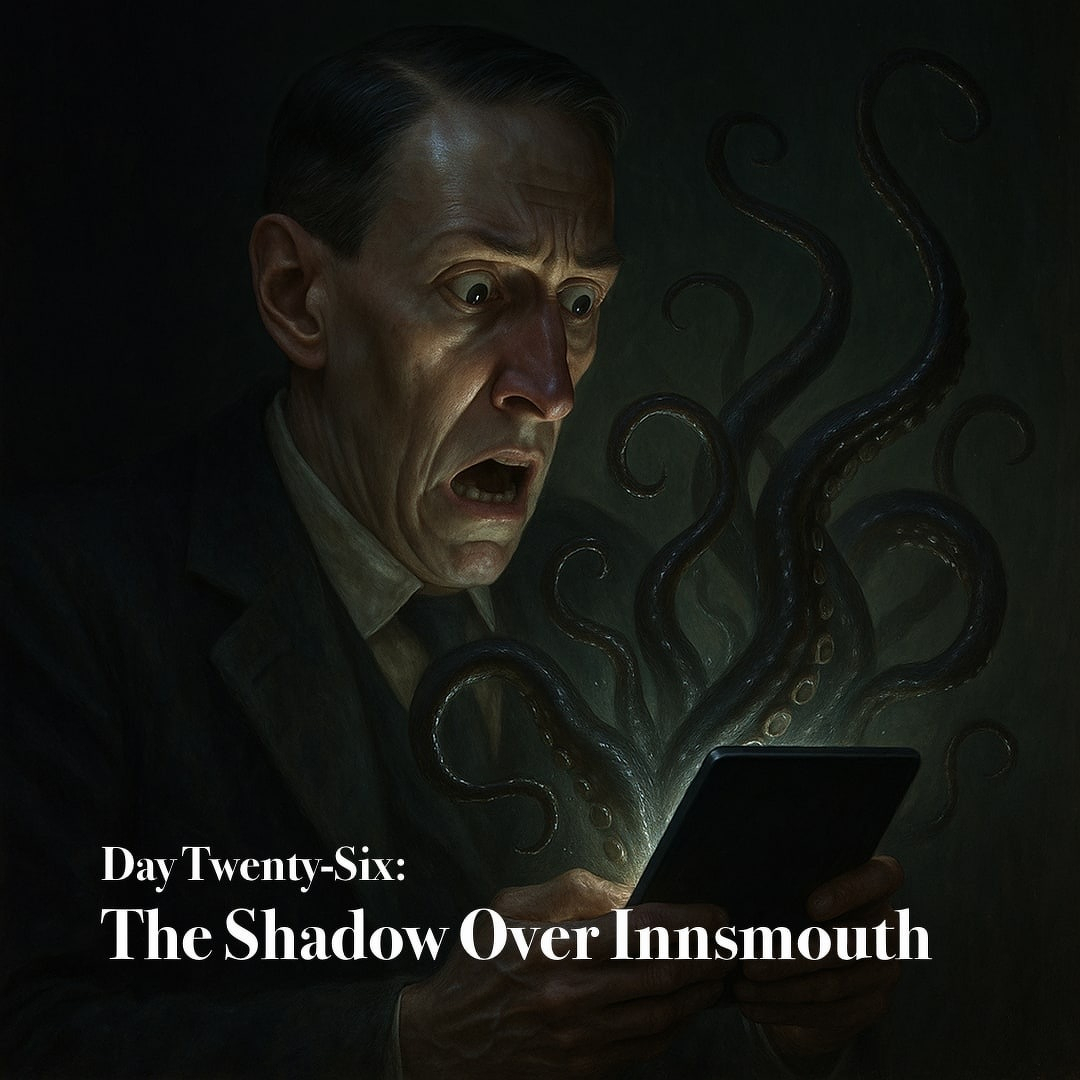

While perusing once more that accursed narrative, The Shadow Over Innsmouth, I found myself seized by a queer and troubling illumination. Though I have wandered its blighted pages oft before, this time the tale unfolded as though through a glass of alien tint. As I traced the narrator’s doomed passage toward that forsaken port, my mind’s eye conjured not the words alone but the dreadful imaginings born of later interpreters. Alan Moore in his grand and blasphemous Providence, and Charles Stross in the eldritch labyrinth of his Laundry Files.

When Moore’s protagonist boards the bus bound for Innsmouth’s rotting wharves, I beheld, in my inward sight, Jacen Burrows’ stark delineations: the weary passengers rendered with the precise horror of Moore’s scholarship, each face betraying the secret ancestry of the sea. Moore, delving deep into the lore and time of H. P. Lovecraft himself, had painted a vision both authentic and damned; thus his Robert Black, riding amidst those ill-omened travelers, has become for me the very image of that doomed town’s breed.

Yet it was Stross who deepened my unease. For I could not read of the Deep Ones’ dominion without pondering, with cold wonder, the consequences of a shared world—ours and theirs—teeming with secret treaties and abysmal politics. What judgments must these primeval beings pass upon our kind, who foul their ancestral waters with the detritus of our brief dominion? And, more dreadful still, how might they answer when the seas they claim as sacred begin to die beneath the weight of human corruption?

Thus, what began as a familiar reading became a revelation, as though some ancient gate within Lovecraft’s prose had creaked open anew, whispering that the boundary between fiction and forbidden truth is thinner than we dare admit.

Our narrator who would one day bring the doom of Innsmouth first came upon that blighted town by mere chance, in the summer of 1927, while wandering the age-worn highways of New England. At that time, he was a student of tender years, a seeker after the quaint and the curious, knowing nothing of the malignant antiquity that slept behind the mists and salt marshes of Massachusetts’ northern coast. Yet some dread instinct, or perhaps the unseen hand of fate, guided him thither to gaze upon horrors that no mortal mind might safely apprehend.

It was long afterward, when the nightmares would no longer loose their grip, that he confessed his role in provoking the secret federal investigation—the raids and torpedo blasts upon Devil Reef that newspapers falsely attributed to Prohibition zeal. Few who read those pallid accounts guessed the true nature of the blasphemies uprooted there, or of the malformed beings carried away in chains to nameless camps.

Our narrator had first heard of Innsmouth in the neighboring town of Newburyport, whose sober citizens whispered of its decay and abominations with furtive glances. Once, they said, it had been a thriving port until the War of 1812 and a mysterious contagion reduced it to ruin. And always there was the name of Obed Marsh—merchant, sea-captain, and founder of a strange religion known as the Esoteric Order of Dagon. The tales told of riots, of vanished townsfolk, and of a pestilence that had spared only those loyal to Marsh’s creed.

With youthful boldness, he boarded the rickety bus that wound through the salt flats toward that forbidden place. What he found defied all natural order. The streets lay hushed and broken, the houses bowed as if sinking into the ooze, and the people—ah, the people!—walked with a hideous gait, their faces bloated, their eyes lidless and unclean, their very skin exuding the odor of the sea. Among them he felt a crawling revulsion, a sense of having trespassed upon some race not wholly of man. Only a pale grocery clerk from Arkham, newly stationed there, retained the aspect of humanity and directed him to seek the drunkard Zadok Allen, last of the old-time townsfolk.

In a back alley by the river, amid crumbling wharves, the old man spoke when the bottle had run low. Our narrator’s tale was a thing of terror and cosmic blasphemy. In the far reaches of the Pacific, Captain Marsh had encountered a degenerate island tribe who consorted with beings of the abyss, immortal Deep Ones who gave bountiful fish and golden relics in exchange for human blood. Marsh had brought their worship to Innsmouth, and when pious men sought to end it, the sea itself rose to avenge its chosen. Thereafter, the survivors interbred with those batrachian demigods, begetting hybrids who, when age came upon them, sloughed their human guise and sank forever into the city of Y’ha-nthlei beneath Devil Reef. The cult, now led by Marsh’s monstrous progeny, sought dominion of the earth through protoplasmic servitors called shoggoths.

As Zadok raved, the listener felt the gaze of unseen watchers and fled his company. The old man was never seen again. That night, when mechanical failure stranded him, he was forced to seek lodging in a pestilent inn whose warped timbers groaned beneath unseen weight. At midnight came a stealthy fumbling at his door and the wet susurrus of inhuman voices. Escaping by window, he crept through alleys where the moonlight revealed scales and gills glistening on figures that searched the streets. Beyond the town’s edge he witnessed a procession of the Deep Ones themselves—frog-headed, grey-green, and malignantly sentient—and swooned at the sight.

Our narrator awoke in Arkham, miraculously unscathed, and soon after brought his account to the authorities. The raids followed; Y’ha-nthlei was bombarded, and Innsmouth’s spawn were dragged screaming from their lairs. Yet triumph was hollow, for in the months that followed he uncovered a truth more dreadful than any he had exposed. His grandmother had been of Obed Marsh’s line, and her mother, a name never recorded, was the sea-demon Pth’thya-l’yi herself. His uncle, discovering this same lineage, had escaped the curse only by self-destruction.

By 1930, subtle changes had begun to manifest. His speech faltered into alien idioms, his eyes grew wider, his flesh took on that clammy sheen he once abhorred. Dreams of the deep assailed him nightly, of luminous temples and ancestral voices calling from the abyss. In time he knew the transformation was irrevocable.

Thus, on a night heavy with salt wind, he resolved upon his final act, not of resistance, but of surrender. Our narrator would free his cousin Lawrence, already far gone in the metamorphosis, from his sanitarium cell. Together they would descend to the sea, where their immortal kin waited in the black splendor of Y’ha-nthlei. There, in the endless twilight of the deep, they would take their rightful place among the children of Dagon and Mother Hydra, to chant forever the hymns that mortals were never meant to hear.

In The Shadow over Innsmouth, that most accursed of his sea-born imaginings, Howard Phillips Lovecraft distilled the hidden dreads that had haunted his lineage and his soul, the ancient fear of decay within the blood and the inevitable corrosion of the mind. Both his parents had perished in the sterile despair of asylums, and from that hereditary shadow he drew the black ichor of his art. As in the earlier chronicle of “Facts Concerning the Late Arthur Jermyn and His Family,” he wove a tale of degeneracy and doomed inheritance, yet upon a far vaster and more blasphemous stage, where the mind recoils before the unveiled immensities of the cosmos. For in this story lies the essence of his philosophy: the revelation that knowledge itself is perilous, that to perceive the true order of the universe is to invite the dissolution of reason.

The town of Innsmouth—its mists, its reeking wharves, its furtive-eyed inhabitants—was born of his wanderings through Newburyport, Massachusetts, that quaint seaport whose ancient roofs lean toward the Atlantic’s gray horizon. Yet beneath that inspiration coiled another influence more malign: Lovecraft’s own revulsion toward miscegenation, a terror of mingled blood that found monstrous expression in the coupling of man and abyssal spawn. His biographers, most notably L. Sprague de Camp, discerned in this a dark allegory of racial defilement; others, such as Robert M. Price, traced the story’s literary ancestry to Robert W. Chambers’ “The Harbor-Master,” Irvin S. Cobb’s “Fishhead,” and H.G. Wells’ “In the Abyss”—each whispering of amphibious abominations that mock the boundaries of mankind. And from Lord Dunsany’s tranquil dream-deity Yoharneth-Lahai, Lovecraft drew a blasphemous inversion: Y’ha-nthlei, the jeweled city beneath the waves, where Cthulhu’s spawn chant hymns of madness in the deep.

Lovecraft himself regarded the tale with bitter distaste, lamenting its “hackneyed rhythm” and coarse style, calling it “one of the lousiest jobs I’ve ever seen.” Weird Tales spurned it, deeming it too long, until in the twilight of 1936 it crept into print through the obscure Visionary Publishing Company, his only bound volume in life, a thing of errata and disfigurement redeemed only by the shadowed artistry of Frank Utpatel.

After his death, when the seas had long reclaimed the year of his birth, Weird Tales would publish an abridged ghost of the work. Critics such as August Derleth and de Camp later hailed it as one of his finest invocations of dread, its oppressive atmosphere broken by the rare vigor of the Innsmouth chase—a sequence wherein his prose, normally still as ancient tombs, burst briefly into violent life.

Now, in the modern age, The Shadow over Innsmouth endures as one of Lovecraft’s most fateful utterances, a scripture of cosmic horror, sung in the voice of madness. Yet beneath its grandeur, the discerning ear may still detect the trembling of its author’s own racial fears and hereditary torments, the echoes of an inheritance he could neither escape nor wholly deny.