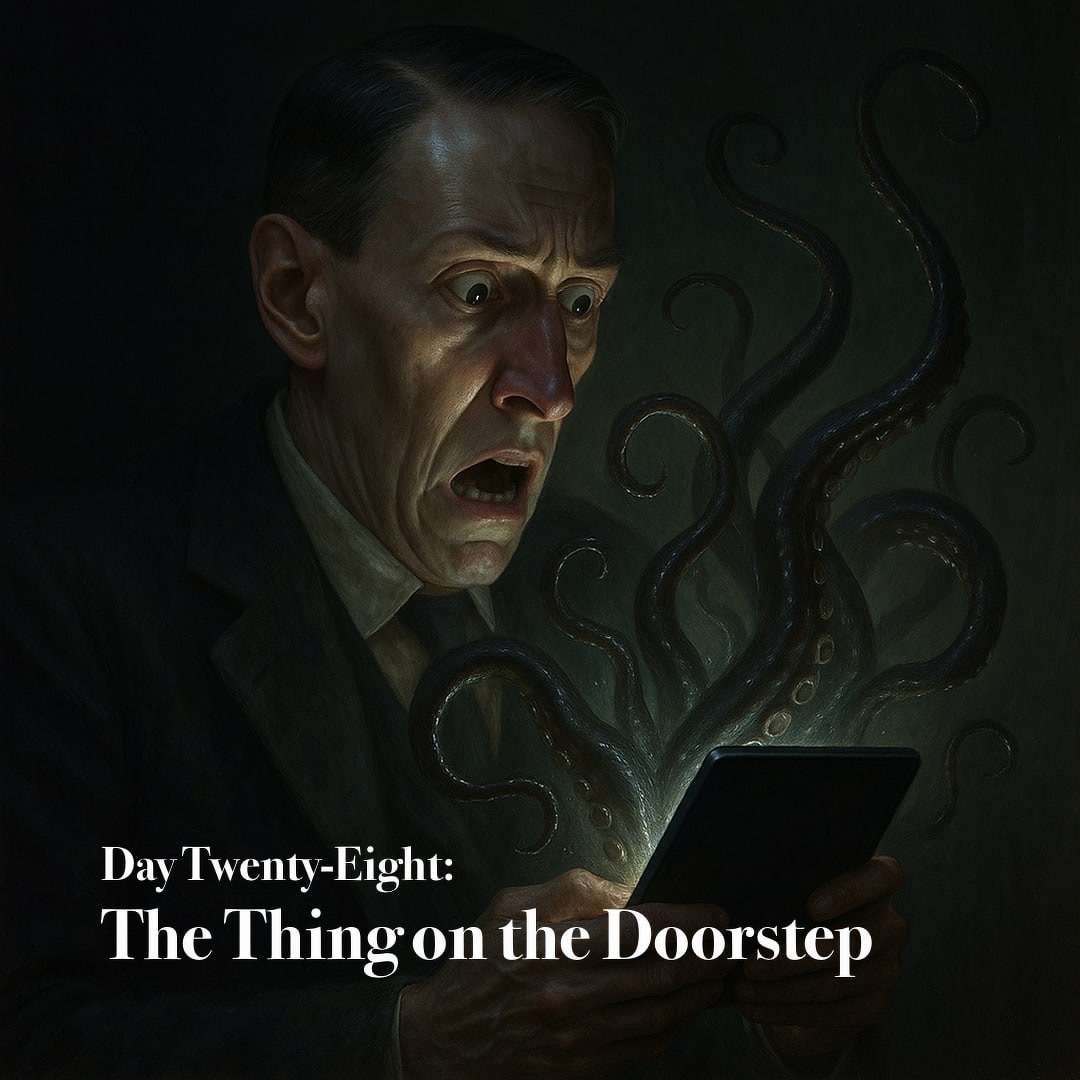

The Thing on the Doorstep

As the waning days of October cast their lengthening shadows across my weary mind, I must confess that my self-imposed ritual, the perusal of one tale each eve from the dread canon of H. P. Lovecraft, has begun to weigh upon my spirit. What once commenced as a reverent communion with the ineffable has grown into a grim observance, as though some unseen watcher demands my continued devotion beneath a pitiless moon. Though I have gleaned strange meditations upon the vast, indifferent gulfs that yawn beyond mortal comprehension, I shall not mourn the passing of this haunted month.

And now, with trembling hand and quickened pulse, I turn the page to that abominable narrative known as “The Thing on the Doorstep”.

Daniel Upton, burdened by unspeakable guilt, sets down this account to prove that madness, not malice, guided his hand when he slew his dearest friend, Edward Derby. From boyhood, Derby had been drawn to the forbidden, his mind ever fixed upon the black vistas of the unseen cosmos. A child of indulgence and fragile constitution, he leaned upon his mother as upon a pillar of light; when death took her, the light guttered, and he wandered long in shadow.

At Miskatonic University his path crossed that of Asenath Waite, pale daughter of Innsmouth, whose gaze bore the cold weight of the abyss. Whispers told of her father, Ephraim Waite, whose sorceries had not died with his flesh. Derby, bewitched by her intellect and by darker charms, wedded her and took up residence in the mouldering Crowninshield House, attended by servants whose eyes held the sheen of the sea’s depths.

Soon, he perceived the slow corrosion of my friend’s soul. He would depart in the dead of night, though he had never learned to drive, and return huddled in his own car like a man escaped from hell. His speech wavered between terror and confession: Asenath, he claimed, could bend his will; could even take his body as her own. Once he whispered that her father yet lived within her. His eyes, in those moments, were no longer human things.

Later, found raving in the wilds of Maine, Derby spoke of an unholy exchange, his flesh no longer his, his mind a host to Ephraim’s immortal blasphemy. Thereafter, his reason crumbled. I placed him in the Arkham sanitarium, though what stared from his eyes was not Edward Derby.

Then came that dreadful knocking: three and two, his old familiar signal. He opened the door to behold a stunted, corpse-like messenger beneath Derby’s greatcoat, bearing a letter sealed with dread. In trembling script, Derby confessed to slaying Asenath, ignorant that her accursed soul lingered. She had claimed his body, leaving her rotting shell to shamble to my door. The thing on the doorstep was he, trapped, inverted, damned. His plea was clear: destroy the abomination in the asylum before it could find another vessel.

He obeyed. He fired the shot that stilled his form: but even now, in quiet hours, he feel the unseen eyes of Ephraim Waite upon me, and I dread the moment when he, too, shall hear that infernal knocking at my door.

Lovecraft conceived “The Thing on the Doorstep” from a 1928 dream he recorded: a man kills his wizard friend to save his soul, walls up the body, but the sorcerer’s spirit swaps bodies, leaving the man a conscious corpse. The tale weaves together Lovecraft’s wider mythos, invoking Arkham, Innsmouth, Miskatonic University, the Necronomicon, and entities like Azathoth and Shub-Niggurath. It revisits his recurring theme of mind-transference, later refined in The Shadow Out of Time.

Possible inspirations include Barry Pain’s An Exchange of Souls and H. B. Drake’s The Remedy, both exploring body-swapping and posthumous possession. The story inspired sequels by Peter Cannon (“The Revenge of Azathoth” and “The House of Azathoth”), and was referenced in Dark Adventure Radio Theatre and Alan Moore’s Providence.

Critical reception remains divided. Peter Cannon, S. T. Joshi, and Robert Weinberg call it among Lovecraft’s weakest works, faulting its melodramatic plot and lack of cosmic depth. Lin Carter dismissed it as a “sordid domestic tragedy” devoid of grandeur. L. Sprague de Camp, however, judged it “middle-rank Lovecraft”—stronger in character than most Weird Tales fiction. Despite mixed opinions, it endures in literary recognition as the sole Lovecraft story included in the Library of America’s 2009 American Fantastic Tales: Terror and the Uncanny from Poe to the Pulps.