Operation Watchtower

Sunday, May 25, 2025

The World Behind the World

Agent Nicholas Grayson. Where were you before you realized you were suspended in darkness? How much time passed before you became aware of the darkness? And what triggered the passing from the experiential you to the analytical you, the you that is an I? The authorial I. And why?

There are glints in your eye. Impossible glints. Mauve. Blood red. Green like deep forest at dusk. But there is no light. No light to glint from. And still, they glint.

You are a boy. It is night. Indiana. Cornfields. Overhead, the thing hovers. Motionless. Waiting. For you.

Darkness.

You are a man. Inside a gas station. A scream. Dogs barking. Rocío yells “Fuck!” Sharp with fear and warning and a thing unnamed.

Darkness.

You are younger. Before you, the oil towers. They burn like altars. Among them, a shape. Something not born of man. Arms too long. Head low. Watching.

Darkness.

Kurt Maurer claps your back. The sound like meat on butcher’s block. His hair red, cropped. His beard saltbitten. He laughs. Opens the door. Inside, the gang bang awaits. Fat men inked like war gods. Women straddling them, roaring. The end of the world a carnival of flesh.

Darkness.

Corinne holds a card to her brow. Her eyes fixed on you like she’s looking through your skull to the brain it contains.

“Now, darling. Tell me. What shape do you see?”

You squint. The world swims.

“It’s a green … star?”

She flips the card. A perfect golden circle. Her breath slow. The faint crease of disappointment.

“Let’s try again.”

Darkness.

You are in the safe house in Chula Vista. South Glass, Carrick called it. The room reels. At your feet, the dead infant dissolves into the filthy, concrete floor. It’s flesh bubbles and sizzles. And then it is gone, leaving a greasy smear.

From outside Rocío again.

“Fuck! Fuck! Fuck!”

Repeats the word like it’s a mantra.

Carrick bolts for the door.

“Ro?”

His voice full of fear and concern.

“You okay?”

But no one is. Not now. Not ever.

You have no idea how long you have been asleep. Your pants still stick to you from your nocturnal emission from your nightmare. The air is frigid. Your breath streams from your mouth.

The blue plastic tarp hangs slack between you and the girl. Belle. Motionless.

She gasps.

A small sound. Sharp. Alive.

But she says nothing. She does not move. As if the cold has claimed her, too.

You step outside. Streetlights buzz. Somewhere distant, a siren winds down. The neighborhood dogs bark wildly. From windows, backyards, porches. They bark like they smell blood. Or something worse.

Carrick stands with shoulders squared, speaking low and calm like he’s handling a spooked animal. Rocío backs against the chainlink fence, her breath coming fast. One hand grips her thigh for balance, the other clutches her gun, not quite aimed—but ready.

She doesn’t blink. Doesn’t speak at first. Her mouth moves, then—

“It came through the wall.”

She jerks a thumb over her shoulder toward the rear wall of the safe house. Carrick says something, quiet, trying to steady her. Ro cuts him off with a sharp gesture.

“It came through the wall, Carrick! I saw it.”

She shakes her head. Her eyes are wide and glassy.

“It was a woman. I think. The shape, anyway. Large. Masiva. No face. Just this… torso. Black. Not shadows—like it ate the shadows. I swear to God, it passed right through me. Then, through the fence. And then—then it went into the building. Across the street. Like it knew where it was going.”

She points. Light from a window flickers once, then goes dark.

No wind. No voices. Just barking. And a silence that feels loaded. Like the world holds its breath.

Carrick turns to you. “You see anything, Grayson?”

“No.” You say.

Though the night is cool, you feel the sweat bead on your skin.

Woman. Shadow. Torso.

The words pull you backward. Not gently. Not with mercy.

To the days when you were fresh out of the Corps. When your hands still remembered the rifle like it was a part of you. When you still believed the war had an outside to come home from.

You see the halls again. The classrooms. University of Southern California. The sunlit corridors of the surface world and the dark things buried beneath it.

Project Delphi.

Where you first learned a shadow could speak

And you?

You listened.

The air in Los Angeles hangs warm in the lungs, thick with exhaust and orange blossom. It’s September of 1991, and the skies over USC shimmer with that Southern California haze, the kind that makes everything feel like it’s waiting to become something else.

You stand at the edge of campus, your backpack slung over one shoulder, boots scuffed from sand and tarmac. You have been out of the Marines for barely three months.

You met up with Whittaker when you got into town. He’d joined the academy, said the uniform felt like armor and the badge like a weight he could carry. He took you out drinking. Got you good and wrecked. You threw up behind a bar that didn’t have a name worth remembering.

What surprised you wasn’t the drink. It was that he didn’t drag you out chasing tail like he used to. No strip clubs. No neon sin. Just two men in their youth, sitting with the silence that comes after the bottle runs dry.

He let it slip between drinks. Said he was seeing his high school girl again. Said he might marry her this time. Like saying it out loud made it real.

Then he looked at you. Asked if you were seeing anyone.

You told him no.

And it was the truth. Because a relationship wasn’t just far from your mind. It was buried. Under rubble. Under ash. Under the part of you that still dreamed of coming back whole.

The gates of the University of Southern California rise like something out of a brochure. Brick buildings trimmed in white stone. Lawns clipped with precision. Palm trees motionless in the late heat. Students drift past with Walkmans and textbooks, laughter rising in easy waves.

But you are not here by accident.

Back at the Greyhound station, an envelope waited for you, with a return address you didn’t recognize. Inside was a one-way cab voucher, a student ID with your photo already laminated, a class schedule heavy in psychology and law, and a seminar cryptically labeled “Special Research—DLPH.”

Alton Rusk, the agent who first pulled you out of staging in Qatar and offered you the “civilian transition package, told you flatly: “You’re an investment now. General Virek made sure of that. Your tuition’s paid. Your housing’s arranged. All you have to do is show up and sharpen.”

You had asked to sharpen what.

Rusk lit a cigarette and looked out the car window. “Whatever edge you came back with.”

You walk past the Leavey Library, where the windows reflect only sunlight and nothing else. You pass the Grace Ford Salvatori Hall, where the air feels colder, and the shadows stretch too long. You feel the eyes on you before you see anyone watching.

A professor in a linen suit nods without smiling. A student hands him a flyer without a word—something about lucid dreaming and group consciousness.

None of it feels real. And yet, none of it feels unfamiliar.

At the edge of the science quad, a woman with platinum blonde hair in black sunglasses pauses as she passes you. She speaks without turning her head: “Welcome to the world behind the world, Mr. Grayson.”

Then she’s gone.

Your first week at USC adjusting to civilian life goes by in a blur

You sit on the edge of your mattress. White walls. Linoleum floor. Government-issued sheets. You hold a book in your lap—The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Your reflection in the darkened window looks older than your ID says you are.

The next day, the campus sprawls like a map too neatly drawn—red-brick buildings, bell towers, palm trees lined like soldiers at ease. Students laugh and drink coffee. Radios play Nirvana and Ice Cube. There’s sun in everything. Different than the sun in The Desert

You’re in a classroom. Violet Adorno, or “Vi” as she likes to be called, sits backward in her chair, camera already rolling. Bleached hair tucked under a thrift-store Dodgers cap. Eyeliner smudged into defiance.

She studies you and says, “You look like someone who’s been edited too many times.”

She films you.

One afternoon, a protest forms near Tommy Trojan. Cardboard signs. Drums. Tie-dye. Sunglasses. Hand-rolled cigarettes.

Jonah Cheevers, one of your classmates, approaches barefoot, holding out a plastic bottle of water.

“Nice to meet you. Seen you in class.” He says, “You don’t seem like the protest type.”

“I’m not. What are you protesting?”

“What do you got? “He jokes. “But seriously? Government’s killing people over oil, and they’re working on some sort of trade agreement that’s going to take away jobs and ship them to third-world countries. You’ll see”

“That sounds like so much foolishness.” You pronounce.

“Okay, man.” He says. “You ever change your mind? You know where to find me.”

He turns and walks back to the protest, shaking his fist.

During your Chemistry Lab, Elena Cao frowns at your notebook. She’s in a lab coat, gum clicking between her teeth, tattoos of neurons peeking out from her sleeves.

“You missed a decimal. Unless you’re trying to blow us both up.”

You correct it. She doesn’t thank you.

One night on the campus, Vi points her Super 8 at you as you sit on a bench, eyes closed, focused on your breathing. The camera whirs. You open your eyes and see her.

“This is for my project. Working title: The Last Honest Face in Los Angeles.”

The gaze of the camera eye makes you uncomfortable, as does the subject of her film. You get up and walk away. She doesn’t follow. Just keeps filming.

One day, before dawn, you bolt upright in bed, gasping. Sweat on your back. Blood in your mouth from biting your tongue. There’s no sound, but you think you hear breathing in the corner of the room.

In the library, Elena sits across from you, books spread out. You stare through a page. Your hand shakes.

Elena punches you in the shoulder. Hard.

“Hey,” she says, “Come back.”

You exhale. Nod. But in your mind, you’re still in The Sandbox.

One night on the campus, Jonah sits cross-legged under a jacaranda tree and sees you walking by. “You’re not the same man every day,” he says. “You know that, right?”

“What do you mean” you snap.

“Whoa, easy buddy. None of business, but you look like you’re going through something. And it show.”

It’s afternoon, and you’re at the campus cafe.

Vi edits her short film. In the frame: you looking away from the lens. Smoke curls behind you. For a second, you look like someone else entirely.

She rewinds it.

Watches again.

And then… the basement. The unmarked door.

You stand before a nondescript door beneath the psychology building. Your hand hovers over the knob. A whisper of cold air leaks from the seam.

A plaque reads simply: RESEARCH – DLPH

You enter.

The room beyond is a hollow square of cinderblock and silence.

One long table under a bank of flickering fluorescents. The air still. Stale. Smelling faintly of salt, dust, and old sweat. A camera mounted in each corner, unmoving. A mirror runs along the back wall.

There are four others already seated.

One sits like a soldier at rest. Back straight. Hands folded. You like her military bearing. Her braid drapes over one shoulder like a black rope. Her boots rest on the floor. Her eyes—pale, silver, unreadable—watch you not with surprise but calculation. She gives the slightest nod. A concession. Or a warning. The sticker on her blouse reads SOFIA VALENTE.

Seated next to her, the man leans forward slightly, fingers pressed together. His skin bears scars. Ceremonial, you think. You think they look badass. His robes hang loose. His gaze lifts to you slowly. There is no expression. But something shifts behind his eyes—recognition or dread. Or both. He breathes through his nose and lowers his head, as if in prayer. His sticker reads EZRA DACOUR.

Next to him is a girl who grins the moment you enter the room. Her orange hair frizzed like static. Black mesh sleeves torn at the elbows. Definitely someone you’d like to get to know more of. She chews bubblegum. Blows a bubble, then pops it. She winks. Blows a kiss. Then laughs.

“Oh, good. The knife showed up,” she says, tapping her pink Hello Kitty backpack like it contains something alive. The sticker across her Slayer t-shirt is upside down. It reads MARA ELLISON.

Then—last—Silas Mercer.

He sits at the far end of the table.

His hair short and neat. His hands folded on the table. His posture perfect. Like a photograph of a man in stillness.

But his eyes—green, bright—fix on you with the full and terrible weight of attention.

Not curiosity. Not threat. Recognition.

He does not blink. He does not smile. He simply says, in a voice quiet: “Took you long enough.”

Mercer once told you that if you ever laid a hand on him again, he’d kill you. You knew he meant it. For a split second, you don’t know whether to bolt or rip his throat out. You know Mercer saw the hesitation.

You take the last chair. It is cold. Steel bolted to the concrete beneath.

The table before them is unadorned.

The lights above hum and flicker. Then stop flickering.

A door opens at the far end. Three people enter.

The first is a man of lean constitution. Tall. Gaunt. His suit charcoal. Shirt white. Tie black and narrow. Black nitrile gloves on his hands though there is no surgery to be done. His face like something printed too many times. Hair combed flat, not a strand out of place. Eyes pale and sharp as broken glass. He does not walk so much as unfold forward. He hasn’t said a word and already he commands your respect.

The second walks barefoot.

Hair silver and bound into a long braid. Desert camo jacket open over loose black linen. His eyes do not match—one soft and brown, the other a milky glass orb that moves on its own. He nods once. That is all. You’ve seen his type before, and you’re not impressed.

The last is a woman.

She wears a black sheath dress and red lipstick like warpaint. Her platinum hair swept back in a perfect coil. Her heels clack on the floor.

She walks past you and winks—not playful, not cruel, but knowing.

And you know her.

She is the one from the quad. The one in the sunglasses. You straighten. She has your complete attention.

They stand across from the students now.

Each still. Each watching.

The gaunt man in the black suit speaks first. A German accent.

“I am Dr. Emil Albrecht. Project Delphi is a protocol. You are its subjects. Its tools.

You are not here to be educated. You are here to be measured. Unmade. Reconfigured. Your pasts are irrelevant. Your futures are conditional. We are not interested in who you are. We are interested in what you can become once that is removed.”

He folds his hands behind his back. The room is silent.

The man in the desert camo shakes his head faintly, then speaks.

“What my brother in the grave suit is tryin’ to say is this: You’re not students.

You’re receivers. You’re gonna get stripped down to the part of you that listens, not speaks. Gonna float in silence. Gonna sweat in shadow. You’ll dream things that make language run backward. You’ll wake up and not know whose eyes you’re seein’ through. And that’s the point, man. You ain’t here to pass. You’re here to fracture—just enough to see through the cracks. Oh, and Commander Isaiah Reams. But you can call me “Bluebird.”

He smiles like the Buddha might if the Buddha carried a bayonet.

The woman with the platinum blonde hair speaks last.

“And I am Dr. Corinne Voss. Don’t be afraid. Everything that matters will hurt. That’s just how transformation feels. You’ll experience cognitive dissonance. You’ll hallucinate. Dissociate. You’ll feel eyes in the mirrors. You’ll forget your own name and be better for it. And if you’re very lucky… you’ll see the thing that lives beneath the floor of the world. The truth that bleeds through time.”

She smiles.

“And when you do…” she says “I’ll be right here. Waiting to ask you what it looked like.”

Bluebird

The walls are cinderblock. Cold and humming. The light overhead sputters. There is a chair in the center of the room. Worn leather. Bolted to the floor.

You sit. Barefoot. Shirtless. Wires fixed behind each ear. Electrodes along your spine. A band across your chest recording every breath.

Bluebird walks barefoot across the concrete floor. His braid swings like a pendulum. His field jacket open, his hands empty. His glass eye scans the room as if it sees something moving beneath the paint.

He sets a metronome on the table. Worn wood. Brass hinge. Ticks like a heartbeat trying to remember its rhythm.

He speaks.

“All right, brother. We’re in the deep now. No maps. No mission brief. Just you. And what’s left when the noise runs out. Thoughts, man… They’re meant to be thought. Not worn. Not carved into the body like truth. Circumstances? They ain’t stable. Don’t treat them like steel. They’re driftwood. Subjectivity—flexible. Stretchy. A mood ring, not a compass. No worldview of fact, Marine. Only usefulness. Only what works until it don’t.”

He circles you, slow. Measured.

“You start treatin’ yourself like an object among objects,” he says “You give up the game. Free will? Maybe. But not if you’ve already sold the soul for a discount on predictability. Belief—belief calcifies. It installs reason like drywall and calls it architecture. But it’s still hollow behind the walls. Ain’t no fact in worldview. Just workings.”

He adjusts the electrodes slightly. You flinch.

“Now dig this. The world’s got a new sacrament, and it’s numbers. It wants to count you, track you, box you up in a spreadsheet, and call you person. You get examined like meat, brother. Labeled. Filed. Coded for storage. And a person? A person is a thing that agrees to be predictable. A person is a system of compromises. But a soul…”

Bluebird is silent for a moment, gathering his thoughts before he continues.

“A soul’s wild, man. A soul grows from within. It is messy. It don’t comply. It don’t accept pre-described forms. A soul moves. And when you ignore it, you break.”

He steps in front of you, crouches. You catch a scent of sandalwood.

“Grayson,” he says “You are the expression of a biological actuality. And I say soul because it’s got weight. It’s got mystery. You ain’t a thing. You’re a becoming. Experience held in momentary cohesion. That’s all we ever were.”

Bluebird places a warm, dry hand lightly on your chest.

“This? This is the shell.” he says “The vehicle. But what’s driving it—that’s the question. And the soul? The soul don’t care if the answers hurt. It only cares that you ask.”

The metronome ticks. The wires hum. Your breath slows.

A flicker of something moves across the wall. A shadow without a source. A form without definition.

Bluebird continues.

“Mental health, brother, is a handshake with the culture that raised you. But what if the culture’s sick? What if the picture it paints don’t fit the world you’re standin’ in? That break you feel? That’s the beginning of truth. At first, it’s pain. Then it’s hunger. Then it’s revelation. We teach people to be persons. Persons are manageable. Predictable. The soul? Soul don’t play by those rules. And in a broken world, the soul is the last honest witness.”

Honest. There’s the word again.

The air grows colder.

You shiver. Your eyes close. Your body stills. Your mind opens.

The metronome ticks on. Like a clock counting down. To the moment you are no longer what they told you to be.

You’re gone. For how long, you don’t know. Time folds. Slips its leash. But slowly, the world begins to return. The room comes back first. Then the man in it.

Bluebird.

He stands above you, still as stone. You feel strange. Enlarged. And somehow heavier, like you’ve been filled with something old and mineral and permanent.

When you first met Bluebird, you wrote him off. Another soldier turned hippie. Another casualty of too much war and too much silence, chasing ghosts in incense and riddles. His talk of the soul didn’t match the God you were raised with. Didn’t match the man you’d become. But now, when he speaks, it rings.

Not like belief. Like memory. Like something you knew once and buried.

Things you’ve taught yourself since coming back from The Desert. Things they don’t print in any manual. Things you whisper in the dark when no one’s listening.

Bluebird says nothing. He moves slow. Unfastens the band across your chest, the electrodes from your back, the wires threaded through your scalp. Gentle, like closing the last page of a book read under firelight.

Not procedure.

A ritual.

The end of something.

Or the beginning.

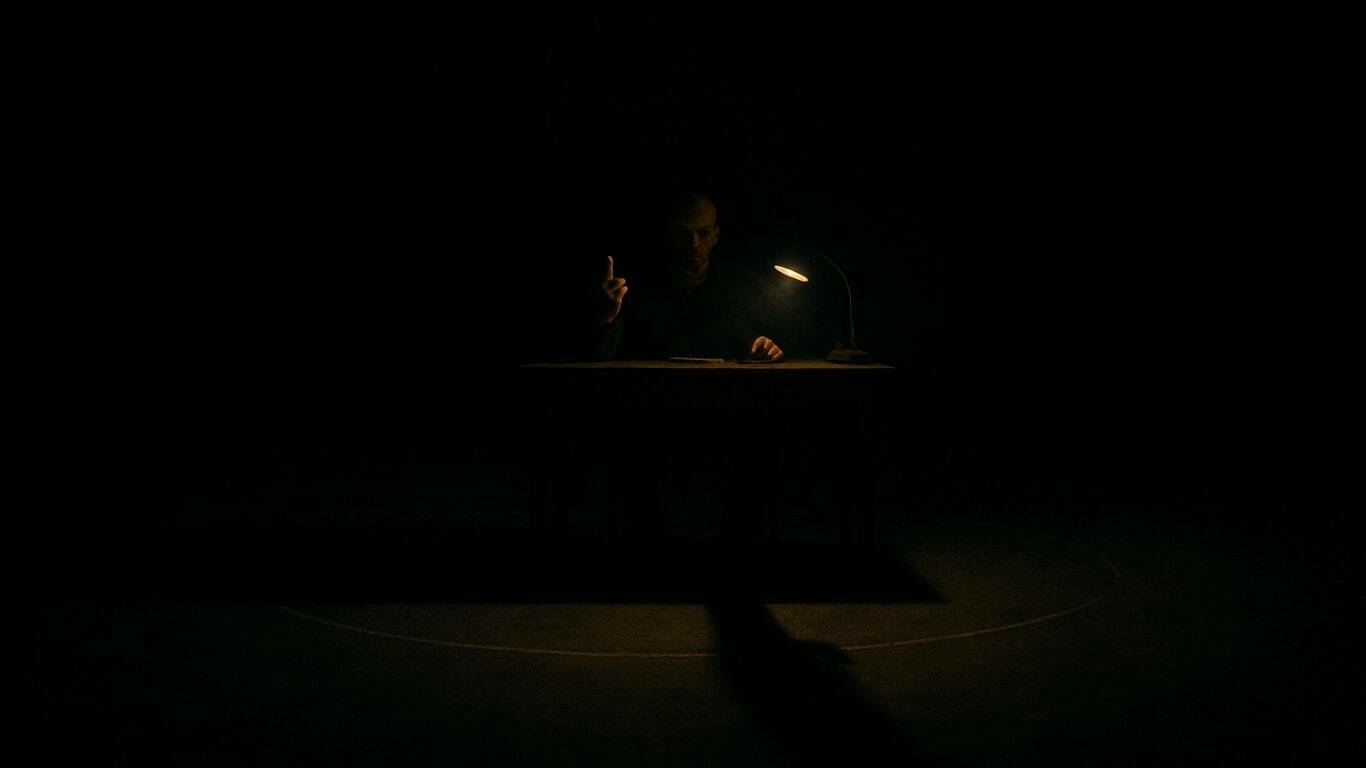

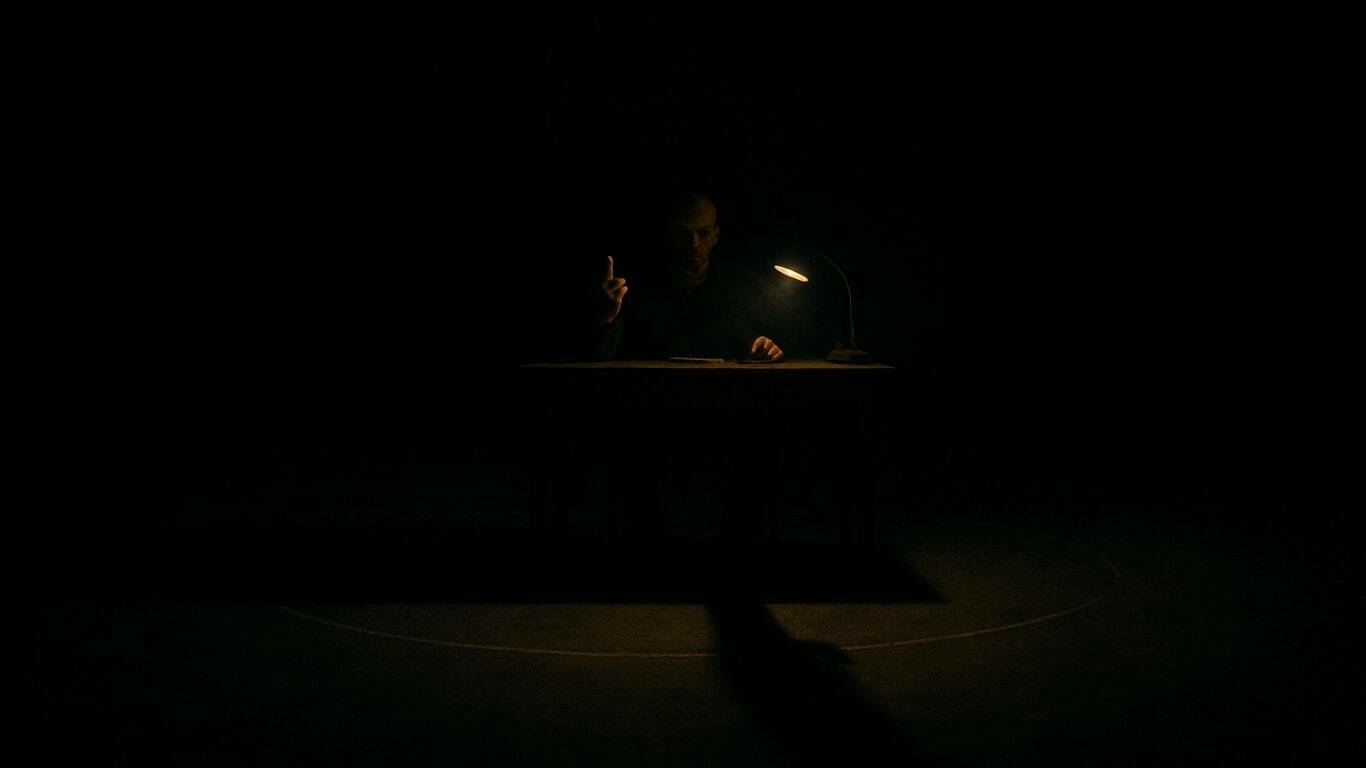

Dr. Albrecht

The room is square and steel. No windows. The walls are lined with cables that vanish into conduits overhead, all humming with unseen current. The floor is seamless concrete, sloped for drainage. The air smells faintly of copper and ozone and something older. There are no lights save for a dim coil above the table.

In the center: a chair made of brushed steel. Thin black straps dangle from the arms like tongues. Beneath it, a grate.

You sit in the chair, wrists bound. Electrodes fastened to your scalp, your chest, behind your ears. A small tube snakes into your nostril, delivering something cold and vaporous. Your eyes are open. Barely.

Across the room, behind a glass partition, Dr. Emil Albrecht stands.

He does not blink.

He wears a tailored charcoal suit buttoned at the throat. Black nitrile gloves pulled tight. His tie is straight.

He presses the switch. The lights pulse once.

You twitch in the chair.

Albrecht speaks into the intercom, voice flat and dissected. “State your name for the record.”

“Nicholas Alexander Grayson.” you reply.

A brief flicker crosses Albrecht’s eyes, as if noting something incorrect.

“What was your mother’s favorite song?”

“Uh, ‘American Pie’.” You realize you’re unsure if it was her song or a song someone told you was hers. Albrecht does not react.

“Do you remember the first time you lied?” he asks.

“Yes.”

“What was the lie?”

You recall the memory. Tell him. “I was with my dad. We were out with our rifles. He told me to shoot a bird. I deliberately missed and told him my aim was bad.”

Albrecht considers your response, then asks, “Are you sure it was the first?”

“What?” you sputter.

The lights buzz.

“What color was the sky the day you were born?”

“I don’t—how could I possibly know? Bright blue, I guess?” you say.

“Not to you.” Albrecht states matter of factly.

Suddenly, you remember screaming—newborn eyes wide—as you beheld a spiraling black aurora above the hospital, seen only by you.

“Which memory did we remove in 2009?” he asks.

“I don’t understand. 2009? I don’t —I don’t know.”

“Then how do you know we removed it?” asks Albrecht. “Have you ever been in this room before?”

“This room?” you ask. “No. Never.”

Albrecht smiles faintly. “Check your left forearm.” he commands.

You look down. There, barely healed, a line of script: “YOU WERE HERE.”

“Who dreamt of you before you were born?”

Your pulse quickens. Your mouth is dry. “What are you talking about? I don’t understand these questions.”

“The question isn’t for you,” he says, writing something in his notebook. “If you walked backward from the day of your death, how many times would you meet yourself?”

“Uh, 7,000?” You say weakly. Your hands begin to shake.

“Which version of you is answering this question?” he asks.

“Me. Me. I’m the only version!” you snap at him. A cold sweat forms.

“The one that’s still pretending.” Albrecht responds. “Last question: What is the last word you will say before you cease to exist?”

“Oh, God.” you groan.

The temperature of the room drops. Your breath comes out of your mouth in whips. The mirror on the wall fogs. A single word appears in condensation: “Corinne.”

Albrecht’s voice in the intercom is flat. “Stimulus cycle one. Phase zero-zero-one. Memory destabilization protocol commencing.”

The lights flicker. Your breath shallow.

“We are not studying thought. Thought is irrelevant. Thought is froth on the surface. We are digging for impulse. Root-level cognition. What the machine of you hides from its own operating system.” he tells you.

The lights dim. A speaker hidden in the wall crackles. Low-frequency pulses emerge.

“What you are experiencing is the reduction of subjectivity.” Albrecht continues. “Your memories do not belong to you. They were installed. Constructed from sensory residue and assigned significance. We will strip them. We will locate the raw feed.”

He adjusts a dial. You wince. Blood runs from your left nostril.

“You are not Nicholas Grayson.” He says, “You are a collection of identifiers. An image formed through repetition. We intend to disrupt the loop. Erasure of name. Then intention. Then structure.”

He turns another dial. A faint strobe flashes from a slit in the ceiling. Irregular. Hypnagogic.

“What is left after narrative is function. What is left after function is void. You are approaching the void.”

You gasp. Your mouth opens but makes no sound. Your eyes roll upward.

“There.” says Albrecht, almost delightedly. “There it is. No language. No boundary.”

He leans forward toward the glass. His voice drops an octave, smooth and insectile. “This is where the useful versions of you begin. And the rest? We will burn away. As we must.”

The lights buzz faintly. The hum of the machines levels out.

Albrecht straightens his tie. Presses the button again. The lights go out.

What happened next, you cannot say. Cannot recall. Only know that you let Albrecht shape you.

Dr. Voss

Dr. Corinne Voss sits across from you, legs crossed, hand resting on a black lacquered box. The room hums low like it’s holding its breath.

She opens the box.

A deck of cards slides onto the table.

“Nicholas… Have you seen these before?” she asks.

She fans the cards in a slow, theatrical gesture. Green Star. Gold Circle. Black Square. Red Cross. Three Blue Wavy lines.

“No, ma’am.” You tell her.

“They were designed in the early 1930s.” she says. “Psychologist named Karl Zener, working with a man named Rhine. Parapsychology, darling. ESP. Clairvoyance. Telepathy. Mind reading, if you’re feeling vulgar. All the things men like our friend Dr. Albrecht call statistical noise. But let me tell you a little secret. The cards weren’t really made to test clairvoyance."

She sets the deck down precisely.

“These cards weren’t really made to measure psychic power. They were made to find cracks.”

She folds her hands. Her voice dips—confidential, almost intimate. “You sit across from someone. You guess the card they’re holding. You get it wrong. You get it wrong again. And again. And somewhere between the fifth and the fiftieth card… you start to wonder if the failure is yours or the system’s.”

She leans forward just slightly.

“And eventually,” she says, “you stop asking if the card is a star or a circle. You start asking if the problem is you.”

She smiles. It’s small and sharp.

“That’s the trick of the Zener deck, Nicholas. It’s not a test of perception. It’s a test of belief. Do you trust what you see… when nothing makes sense? Do you trust yourself to be right, even when you’re always wrong?”

She smiles.

“That’s the real trick of the Zener deck, Nicholas. It doesn’t reveal power. It reveals cracks. And darling… you’ve got plenty.”

She picks up the top card. Doesn’t show it. Corinne holds a card to her brow. Her eyes fixed on you like she’s looking through your skull to the brain it contains.

“Now, darling. Tell me. What shape do you see?”

You feel ridiculous, but you concentrate on the card. “It’s a green … star?” you tell her.

She flips the card. A perfect golden circle. Her breath slow. The faint crease of disappointment.

“Let’s try again.” she says.

She draws the top card. Holds it face-down.

“What shape?” she asks.

“Three wavy lines.” you say after a moment.

She flips it, revealing a black square.

She makes no comment. Shuffles again. Her slender fingers move over the cards.

This repeats. Over and over. Dozens of draws. Hundreds. You guess slightly better than chance. But never beyond it. Three out of five. Then two. Then three again. Enough to suggest something. But not enough to prove it.

She changes the shuffling pattern. Twice. Your success rate does not waver.

The clock on the wall ticks.

“You know, you are not failing. You are avoiding. There is a difference.” she says.’

She shuffles once more, then stops. Her hand rests on the deck.

Her eyes lock on yours. They stay there. The air in the room changes. Warmer, denser, charged like the air before a storm.

“Grayson.” she says.

She does not blink.

“Yes, ma’am?”

“You are too much in your head.” She tells you and pushes the deck aside.

Her voice drops—slow, certain. “We need to shake things up. We need to fuck.”

“What?!? I don’t—I don’t know what to say. Are you sure?” You feel your face redden, radiating heat.

She watches you. No smile. No seduction. Just truth laid out like the cards on the table. She leans in slightly. Her breath is warm. “I know.” she says “ I know that goes beyond the propriety of our relationship. But we need to think outside the box. Don’t you agree?”

“Yes, ma’am, yes I do.”

The room holds still.

The deck of cards sits untouched.

The ceiling light buzzes.

She stands, takes you by the hand, and leads you out of the room.

Isolation Tank

The corridor smells of saline, machine oil, and electricity.

At the far end: four tanks. Stainless steel. Rounded edges. Lids open like coffins.

A fluorescent hum flickers overhead.

Your reflection distorts in the slick surface of Tank One, you in your swim trunks. Your name is written in black marker on masking tape.

Everyone ignores your erection except Corrine, who smiles.

Dr. Albrecht stands to your right. Gaunt. Stark. His charcoal suit is too precise, like it’s been ironed by an algorithm. Blue eyes dead and distant. His black nitrile gloves stretched over hands.

He speaks without turning.

“The isolation tank is not therapeutic. It is not spiritual. It is a controlled environment for the redaction of input and—by extension—identity. When you deprive the nervous system of stimulus, it begins to read itself. Then it begins to rewrite.”

To your left stands Bluebird. His silver hair is tied back in a long braid, his desert-camo field jacket hung open over loose linen robes. One eye is pale and glassy—always watching something beyond the room.

“What he means, Marine,” he said, “is the tank’s like a clean mirror. Only trouble is… you bring in all your fingerprints. Ain’t no noise down there. Just the sound of what you ain’t ready to hear. You float long enough; you stop being a body. You become… resonance.”

Corinne steps forward, heels clicking softly on the tile. She wears a tailored black sheath dress and a high chignon. Her platinum hair glows faintly in the fluorescent haze. She smells of Chanel and cigarette smoke.

“It isn’t about silence, Nicholas.” She tells you, “It’s about the return. The tank strips you. Memory. Identity. Language. Until all you are is presence. And then it asks: ‘What’s left?’”

A lab assistant adjusts dials and throws a lever. The tank hisses. Its lid inches wider.

“You’ll hallucinate. You’ll question time. Eventually, you may ask which you is doing the asking. That’s when the work begins.” Says Albrecht.

“Or ends. Depending on how far you fall.” Bluebird says.

“But don’t worry, darling.” Corinne tells you. “We’ll be here. Waiting to see who climbs out.”

The lab assistant taps the vein in your arms twice and injects a solution into your vein.

Corinne helps you into the tank. You lower yourself into the water. It’s warm as blood.

Bluebird puts a dry, warm hand on your shoulder.

“Listen up, cowboy, your Western notion of time’s not gonna work in there. Aztecs had a way of looking at time that might help. For them, there was no beginning or end. There was only motion. What they called time-place. It’s weave. It’s dance. For them, time wasn’t something you measured. Time’s a rhythm. It’s not that events happen in time. It’s that time-place is the event. Like cloth being weaved from threads. And every one of us a strand in the weave, timed and placed, singing our part in a song that doesn’t end. Am I making any sense, Marine?” He asks.

You see Albrecht roll his eyes through the thick lenses of his glasses.

“Absolutely not, sir.” You tell Bluebird.

Corinne looks down at you as you float. Smiles. “See you in 24 hours.”

The lid closes, and you are engulfed in darkness. You hear the murmur of them talking outside. The sound of Corinne’s heels clacking on the floor, growing fainter and fainter. And then, silence. You float. Sometime later, you feel the rush of the cocktail the lab assistant injected into your bloodstream come on in waves.

You float.

No light. No sound. No weight.

The water is body-temperature salt, dense enough to hold you like a second womb. Electrodes are clipped to you, but you cannot feel them. The tank is sealed. The world, gone. What remains is void. Unmeasured, unbroken.

Then the entheogens unfurl you. A key turned in a lock that was always there, buried in the meat of your brain. No heat. No pain. Just the opening of a door that cannot be seen.

You begin to drift. Not the body. The self.

Out. Away. Beyond.

It feels like space—not the vastness of stars, but something more intimate and ancient. It is darkness without edge, a silence older than language. There is no up, no down, just suspension, the hum of everything, and nothing all at once.

And in that dark—

Everything means everything.

Every breath, every twitch of thought, every ghost of emotion carries a weight it never had before—a superabundance—as if God is watching, not to judge but to understand.

You see your life.

All of it.

Not as memory but as an event, unfurling in layers, spirals, time-compressed and widened into shape, color, and fire.

You see your mother’s womb and the moment of emergence, slipping into the cold, screaming, your father’s hands beneath you. Your mother weeping.

Above you then, even now—a dark spiral, not just a shape but a presence, a truth etched into the ceiling of the world.

You see your father and mother holding you. Then drifting apart, years stretched taut between them like glass. Shards of silence in their smiles.

Your sister, laughing beside you. A girl in church shoes.

You see them both in pews. The hymns. The lies told with love. The smell of dust and faith.

You see the recruiting office, the papers, the oath. The desert—its cruelty, its grandeur. The sun like a furnace. The sand like judgment.

You see Corrine. Her mouth. Her breath. The curve of her spine beneath your hands.

And then—

Bit by bit—

Strand by strand—

It unravels.

The thread of identity has been pulled loose. First, your name. Then, your story. Then, your shape.

The narrative collapses like scaffolding. The narrator fades. The “I” dissolves.

There is no Nicholas.

There is only that which remains.

The thing that watches. The thing that remembers. The soul is untethered, without a name, history, or mask.

And in that final stillness, it sings.

Not in sound. But in resonance. A note from the center of a being that never needed language to know itself. A truth that was waiting for silence. And found it.

Here.

Now.

Forever.

Time passes. You do not know how much, but at some point, you hear a faint sizzling sound. Eventually, you realize it is the sound of the synapses firing in your brain.

You are a boy. It is night. Indiana. Cornfields. Overhead, the thing hovers. Motionless. Waiting. For you.

You are a man. Inside a gas station. A scream. Dogs barking. Rocío yells “Fuck!” Sharp with fear and warning and a thing unnamed.

You are younger. Before you, the oil towers. They burn like altars. Among them a shape. Something not born of man. Arms too long. Head low. Watching.

Kurt Maurer claps your back. The sound like meat on butcher’s block. His hair red, cropped. His beard saltbitten. He laughs. Opens the door. Inside, the gang bang awaits. Fat men inked like war gods. Women straddling them, roaring. The end of the world a carnival of flesh.

Corinne holds a card to her brow. Her eyes fixed on you like she’s looking through your skull to the brain it contains.

“Now, darling. Tell me. What shape do you see?” she asks.

You squint. The world swims.

“It’s a green … star?”

She flips the card. A perfect golden circle. Her breath slow. The faint crease of disappointment.

“Let’s try again.” she says.

The grass wet with dew. Cold against your bare feet. You step out into the corn.

The stalks crowd close. Tall and dark and whispering. In the rows ahead something hangs. Hovering like a shadow made whole. A woman maybe. Or something that wore one once.

Its face pale. Hollow. The skull beneath near showing. A robe hangs off it like a ruined flag. Black. Tattered. Stinking of soil and smoke. It shifts in the air like a thing caught between motion and memory.

“Lo, my child,” It hisses. “To fashion thee into the instrument of mine own purpose, I must needs take the scales from thine eyes, yea, even thy innocence must I strip away. For I am the whetstone, and thou art the blade; and by mine hand shalt thou be sharpened.”

It comes down.

No sound. Just descent. Like a thought you can’t stop having.

It presses its mouth to yours. A tongue, cold and wet, snakes between your teeth.

It keeps coming. You try to breathe but you can’t. You try to pull away but you don’t. The taste is of stone. Of stagnant water.

You gag. Still, it comes.

Longer than breath. Longer than time. And still, it comes.

Your eyes are slitted. Tears roll down your face, and through them, you see something behind the thing that has its tongue down your throat.

It floats.

No wings. No sound. No wind stirred by its coming.

The thing is all curve and swell and obscene abundance. What floats before you is meat, and meat gone bad.

Its grey flesh pulses. Sick and wet. Veined with black rot. Swollen breasts hang like tumors. The belly ripples as if something beneath it still kicks, still feeds. The skin splits in places. Ruptures. Leaks. Worms writhe from folds like thoughts that should not be thought.

The head is eyeless. Faceless. Braided coils of hair molded in clotted sinew, looped like entrails. Where the mouth might be, there is only an open slit, yawning. A stink rises from it.

It drifts forward. The air grows heavy.

Low and wet and crawling through the roots of your spine.

Your body remembers.

It does not look at you.

It does not need to.

It already owns you.

Sunday, May 25, 2025

Push the World

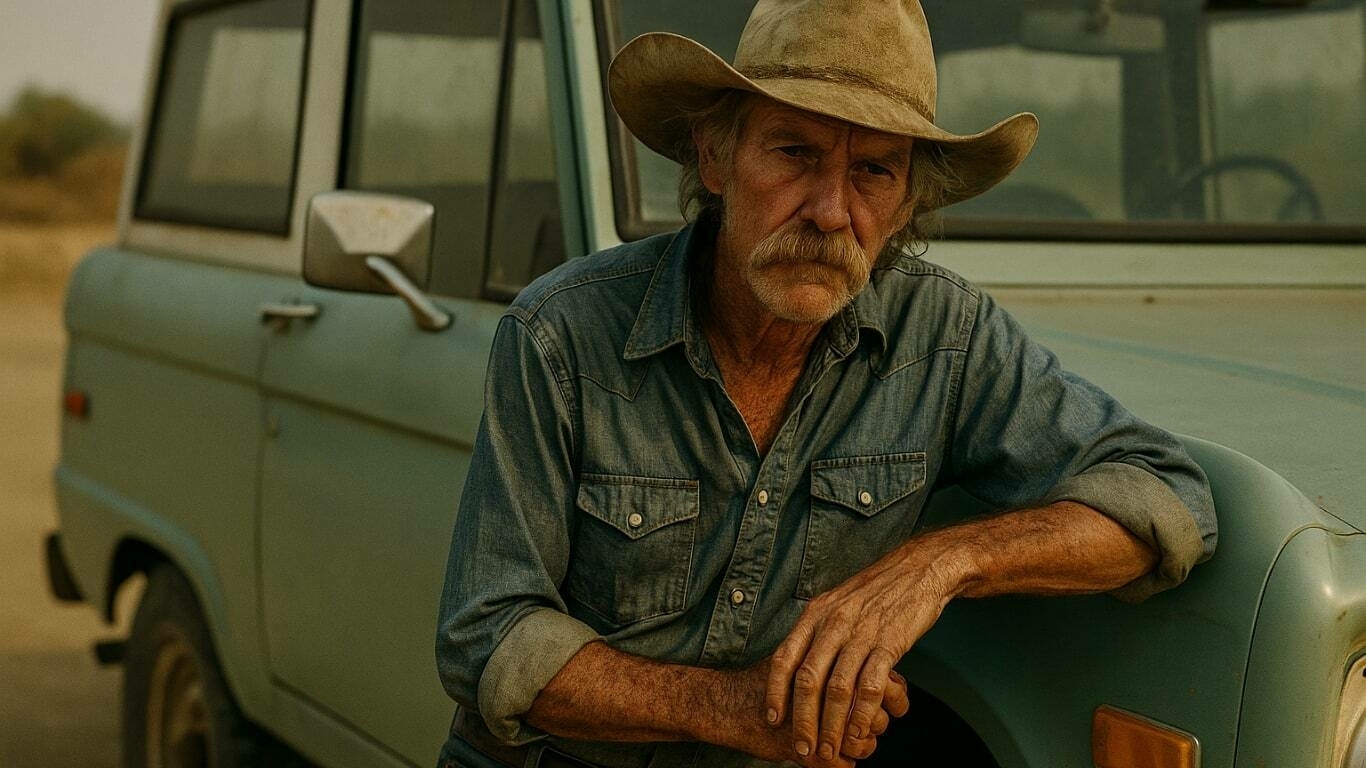

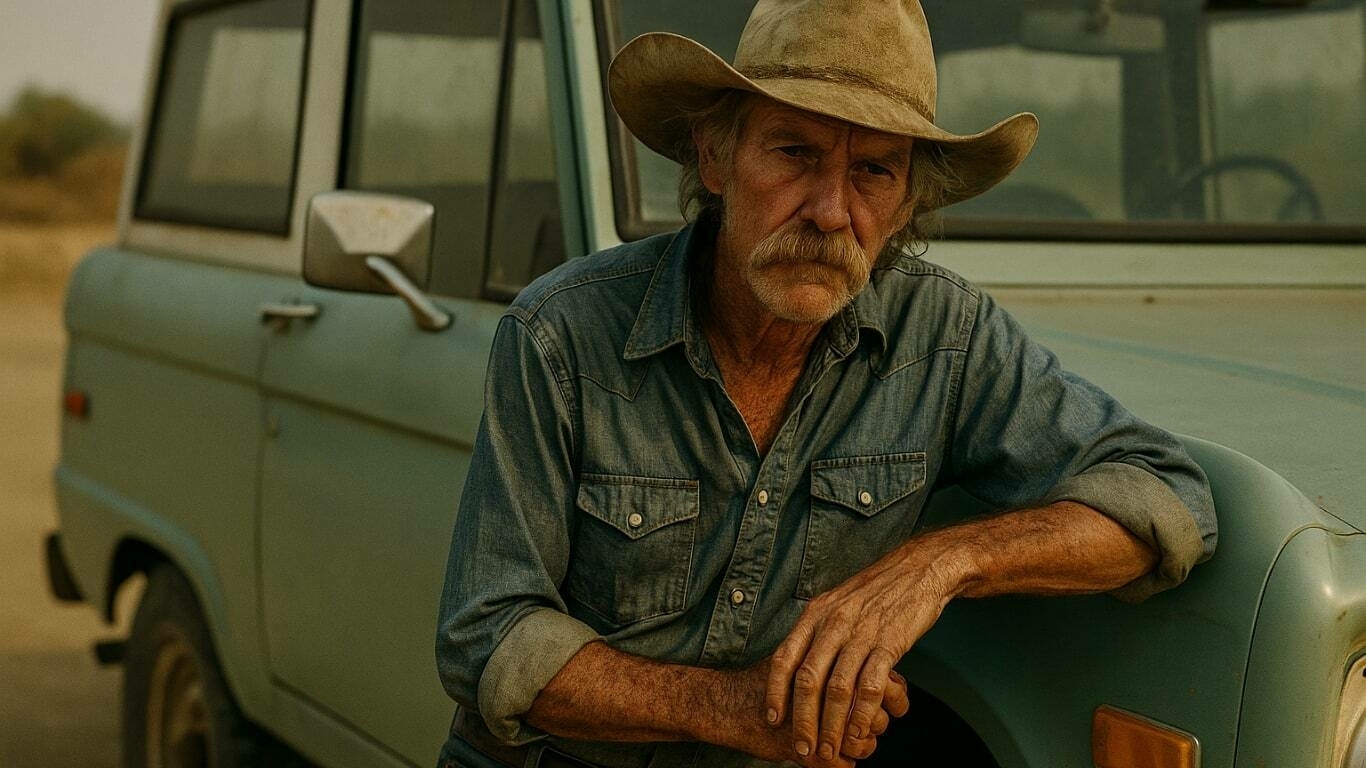

Bryce Wexley. You are bone-tired.

The woman called Trenody left you alone in a bedroom. The bed wide as a pasture, the ceiling fan ticking like a distant clock. She showed you the frame. The thing in the frame. You saw it but you did not understand it. The towers falling? Alpine? The room that does not exist? The message that you are the door? Your perfect twin? A face like yours but not yours. Eyes in the sky? Their gaze fixed eastward.

You do not know what it means.

There is a knock at the door.

“Senator? Mister Wexley? May I come in? I need to speak with you.” Trenody says.

“Come in.”

You rise. You open the door. Trenody stands there. Her eyes are a question she does not ask.

“I know it is late, but I have to know.” She says.

She crosses the room. Takes up the remote from the nightstand. Aims it at the enormous rear-projection television. The screen flares to life.

And there you are.

No. Not you.

Your twin. Your shade. Standing in the rubble of a ruined city, soot-smeared, hair tangled, holding a woman who weeps without sound. He is rugged. Heroic. On the lower third of the screen the words: Senator Wexley Onsite at the World Trade Center.

Trenody watches.

“If that is Senator Wexley, then who are you?”

She sits on the edge of the bed.

“He’s my doppelgänger. Made by the aliens. I am going to kill him.” You say.

“You look like him.” She says, “Except you are leaner. And you have seen things. Like me.”

Her face goes pale at the word. She sits forward. Near the edge now.

“Kill?" she says.

You nod once.

“With a gun,” you tell her. “I’ll have Vince put a bullet between his eyes.”

She looks at you. Eyes wide, voice quiet.

“But,” she says, “all the flights are grounded.”

You scowl. A slow tightening of the mouth. The breath held too long. You had not considered that.

“The aliens. It keeps coming back to the space aliens.” She says, “They are not gods. They pretend to be. They are keeping us from the Next Level. And the ones who help them, the Luciferians. They are human. They wear skin like ours. But they are not like us. And they want something from you. I do not know what.”

“It’s a long and complicated story.” You tell her.

She lowers her voice. “I am a simple girl. Texas born. Ti and Do—they showed me the way. But you come from a wealthy family. You might as well be royalty. To think we would be under the same roof. What strange destiny led you here?”

That word.

Destiny.

It draws the dust off an old memory.

The sun going down over the Pacific. You, five years old, astride a dark horse beside a man who has never once said “I love you” and never needed to. He is clearing brush in silence, canvas jacket slung over one shoulder.

His boots dusty with the earth.

He is your great-grandfather. Calder Wexley. You never called him that. You called him “Sir.”

He stops. Tethers the horse. Draws a satchel from the saddle.

“Boy, someday all this will be yours. This is your destiny.”

He lifts his arms. One hand holds the manor. The other, the sea.

“The time left to me is short. I’ll make use of it.”

He opens the satchel. Pulls out a steel gauntlet. One from the old suits in the castle hall. It gleams in the amber light.

“In the old days, men understood the weight of signs. Symbol was not metaphor but law itself. To strike a man with a gauntlet was not violence. It was memory made manifest. A blow fashioned not for harm but for permanence. It marked the flesh and the mind alike. A ceremony of pain and spectacle. And all who saw it carried the lesson in silence.”

He draws the armored glove on. Flexes the metal fingers. Makes a fist.

“Civilization has forgotten what pain remembers.”

He turns to you.

“Listen to me, boy, the world doesn’t bend to the strong or the clever. It bends to the one who controls the narrative. The one who holds the story holds the future. Those who make the rules don’t play by them—they rewrite them when necessary. To be the ruler, you must understand that everything is a transaction—money, loyalty, history, even blood. Power is never a right; it’s a thing you earn—through manipulation, force, and the stories you tell. The truth is nothing but a tool in your hand, Bryce, and that truth can be shaped into any form you wish. But remember—truth is power only if you can make others believe it. Never forget that.”

He snaps his arm back, swings, and smashes you in the face. Steel on skin. A crack like thunder in your skull. You’re lifted from the earth, and the sky spins. You hit the dirt hard. Your mouth fills with blood.

You see stars.

He stands above you. The glove dripping red. His boot nudges your face.

“Never forget that.”

You flinch at the memory of Old Man Calder’s blow.

Trenody sees it. She watches you.

“I would give you a penny for your thoughts, but I believe they would cost me more than that.” she says.

“Sorry.” You tell her, “I was thinking about a lesson I was once taught.”

She lowers herself next to you. Slow. Deliberate. Her denim skirt pulls tight at the knees as she sits. She does not look at you. Not yet.

“I know that you and I come from very different places. You were raised in a manor. I was raised next to strip malls. But we are both haunted. That much I can see.” Her voice is quiet. Not soft.

You bridle at the comparison. She’s nothing but a peasant. But what she said about being haunted is true.

She inches closer. Slowly. The warmth of her leg against yours, thigh to thigh.

“It has been a long time since I was intimate with anyone.” She says, “Years, maybe. I do not remember when the loneliness became a habit instead of a feeling.”

She breathes out. Not quite a sigh.

“I know I should not. I know this is not proper. But I need to be touched, and I believe that you do, too.”

She turns slightly.

“I hope I am not being too forward.” she says.

She takes your hand. Moves it with hers. Presses it gently against her breast. Holds it there.

“This is my vehicle. It is how I remain here. It is how I hold the ache. It is how I offer peace to those who need it.”

She closes her eyes.

“I would like to be intimate with you, Bryce. If that is what you wish as well.”

“I do.”

The room is quiet.

No wind stirs the curtain. No noise comes from the street. The world seems to lean in.

Trenody stands before you in the half-light.

She lifts your jacket from your shoulders. Folds it. Her hands find the buttons of your shirt. One by one. She does not rush.

Her breath is steady. Her eyes do not leave yours. She watches you like a woman watching a flame she does not want to die.

“You are still a man, no matter what the aliens have done to you,” she says.

Her fingers trail the hollows of your collarbone. She undresses with quiet purpose. No ceremony. No shame. Her body is not a seduction.

“This is my vehicle.” she says. “It has been broken. But it still moves. It still carries me forward. And tonight, it wishes to carry you.”

You embrace not with hunger but with gravity.

She climbs onto the bed beside you and draws the covers over your bodies. Her hands rest on your chest. Her head on your shoulder.

When she kisses you, it is not passion. It is benediction.

Your bodies move like tide and shore. Slow. Relentless. Old as grief.

No words pass between you.

You have never known this kind of intimacy. Not like this. Not with tenderness. Not with reverence. All your life the body has been a weapon. A lure. A thing used to conquer or be conquered. Sex was barter. Sex was a battlefield. Sex was rutting in the dark like animals blind to themselves.

And sometimes, sex was death.

Charlotte.

Princess Charlotte Eleanor Victoria of Gloucester.

Blood of kings. Member of the House of Windsor by way of the Gloucester line. Twenty-seventh in line to a crown older than most languages. Or was it thirty-seventh? But her Crown was light, and her voice was laughter, and she looked at the world as if it were a stage that owed her no curtain.

Your family’s money made her lineage look poor. Generations of oil and empire. A different kind of royalty. A quieter violence.

She was Regal but unaffected. Known for her striking dark auburn hair, usually worn long and braided in the old court style. Publicly proper, but in private: rebellious, whip-smart, emotionally intense.

You remember her beneath you.

Not tender. Not sacred. Just bodies. Her plaited hair pulling loose with each thrust, her breath ragged, her teeth at your throat.

It was not lovemaking. It was fucking.

You were both drunk. The party in Hertfordshire gone to smoke and murmurs and political lies whispered over cut crystal.

You had the keys to a Jaguar Mark X.

She wanted the wind. You gave her the road. The curve came too fast. The bridge did not move. The car hit stone and folded.

She died where she sat.

Her face crushed and broken on the dashboard.

You crawled from the wreck with ribs shattered, blood in your mouth, and your hands slick with her blood.

The Royal Press Office said she passed peacefully. A lie. The last gift they gave her.

Closed-door funeral. No press. No photographs. Just a redacted page and the smell of lilies.

MI6 swept the floor. Burned the files. General Voss sent a jet and a handler. You were gone before her body cooled.

The Crown forgets nothing. But it sometimes erases.

The world moved on. The line of succession closed around the wound.

But you remember.

You keep her silver cigarette case in a drawer back at your estate.

Inside: A flower, pressed flat like memory. A matchbook from the Wheatsheaf Tavern. And the corner of a love letter. Not to you. From one of the men who courted her. The ink ran pink from the rain the night she died.

After that, your father and mother would no longer indulge you.

They spoke in quiet tones behind thick doors. They hosted dinners where your name was not mentioned. The wine was poured but never offered to you. You were tolerated like weather—something to be endured until it passed or broke.

You still remember the day that sets things in motion to where you are now, Trenody beside you.

You and your father rode out across the land. The same land you and your great-grandfather cleared when you were a boy. The same ridge lines. The same dry winds. Only now, the brush grew back quicker than it once did. Like the earth no longer respected your family name.

Your healing ribs ached with each step your horse took. Father rode ahead. His back straight. His coat was dark against the pale hills. He did not speak and you did not ask him to. The horses breathed steamed in the morning chill. The sky was a lid of pewter and the sun did not show.

Your father’s horse trotted near the old fencepost. The one your great-grandfather marked with a copper nail. He did not dismount. He looked out over the land like it belonged to someone else.

“You understand what you’ve done.” He said. It is not a question.

“Yes, father.” You said, “And I know you and your mother are ashamed of me..”

He did not look at you.

“We don’t recover from things like this. Not really. We bury them deep, and we walk like they’re not there. But they are. And they own us. Forever.”

You looked out at the hills. At the brush that grew wild again. At the sky that wouldn’t break open.

“You’ll inherit all this. But not clean. Not proud. You’ll inherit it like a man inherits debt. And you’ll carry it until it kills you. That’s your future now.”

You rode in silence for some time. The wind moved through the dry grass. The horses made no complaint. The sky above was vast and pale and without mercy.

His father spoke without turning his head. “And I don’t want to hear more talk of you entering politics. Politics is for show ponies and social climbers. It’s theater. And you’re not an actor, son. You’re a Wexley. You’re supposed to be useful.”

“You never approved me of me! You always looked down at me! I know I always disappointed you and Mother!” You snarl.

You crested a rise. Below you, the valley unfolded—acres of land, oil rigs distant, vineyards coiled in perfect lines like snakes at rest. The empire.

“You want to play politics? Buy a politician.” he said “Hell, buy a whole damn caucus. Buy a Supreme Court justice if that’s your fancy. That’s what we do. We don’t run for office; we own it. We don’t make policy. We write the checks that make policy happen.”

He turned, the reins slack in one hand.

“Do as your great-grandfather did. As I did. Stay in the shadows. Push the world with your thumb. Never let them see your fingerprints.” he said.

“No,” you tell him “I’ve made up my mind. I’m going to go into politics. I don’t care what you say.”

Your father smiled. Thin. Cold.

“You still want the limelight? Then go big. Presidency big. Aim for the chair they still believe matters. Put your face on the postage stamps if you can stomach the lies.” He paused. “But you and I both know, you don’t have the balls for that kind of work.”

He turned his horse and rode down the hill.

You stayed where you were.

The wind at your back.

The silence inside you louder than any voice.

That Thing Down by the Docks

Senator Wexley. The phone rings.

You blink as though waking from a dream. You hold a long, black blade, a gem the color of blood in its center. How long have you been holding it? Where did it come from? The room reels.

You steady yourself and carefully lower the sword, setting it down on the polished glass of the end table, careful not to let it touch the marble.

The suite is whisper-quiet, opulent. Everything upholstered in ghost-white or gold. One wall is all glass, looking out over the city’s starlit ruin. Beneath the chandelier, a decanter of whisky sits untouched. The fireplace glows blue with a gaslight that does not warm. The carpet is cream-colored and so thick it steals every footstep like a secret.

You pick up the phone. Your wife. Celeste.

You stare at the name a moment longer than you need to. Like it is a riddle.

Then you answer, already annoyed. “Yes?”

“Darling? I saw you on Tough Talk. It’s completely forgivable why they had to push back the segment on Wexcess.” she says. “They are going to reschedule the segment?”

“I’m sure they will. Is this really what you wanted to talk about, Celeste?”

She won’t let it go. “What’s unforgivable is your only comment to Doherty. ‘Nice suite?’ Really, darling? I’m surprised Loraine did give you a tongue-lashing, especially after all the media training she gave you.” She pauses “You looked… polished. Polished and hollow. And the footage. From the World Trade Center. The one where you’re holding that woman, covered in soot. The networks play it constantly. You know what the strangest thing is?”

“No, Celeste,” you tell her, “I don’t know what you mean.”

“Don’t you?” She asks, “You looked beautiful. Heroic. But it wasn’t you. Not the man I married. Not the way you move when you think no one’s watching.”

“Maybe you’re finally seeing me. The real me.” you say.

“The reason I call, and I do so hate to disturb you at this hour, because Graham’ has been asking strange questions. About dreams. About ‘the other father.’ I caught him talking to a mirror.”

You pinch your brow. “He’s probably gay.”

Celeste is silent. Then has says gently, almost kind, “Come home soon. Not for me. For Graham.”

She disconnects.

Celeste said Graham had dreams about “the other father,” the other you. Everything keeps coming back to Alpine. And meeting Caruso set fateful night in motion.

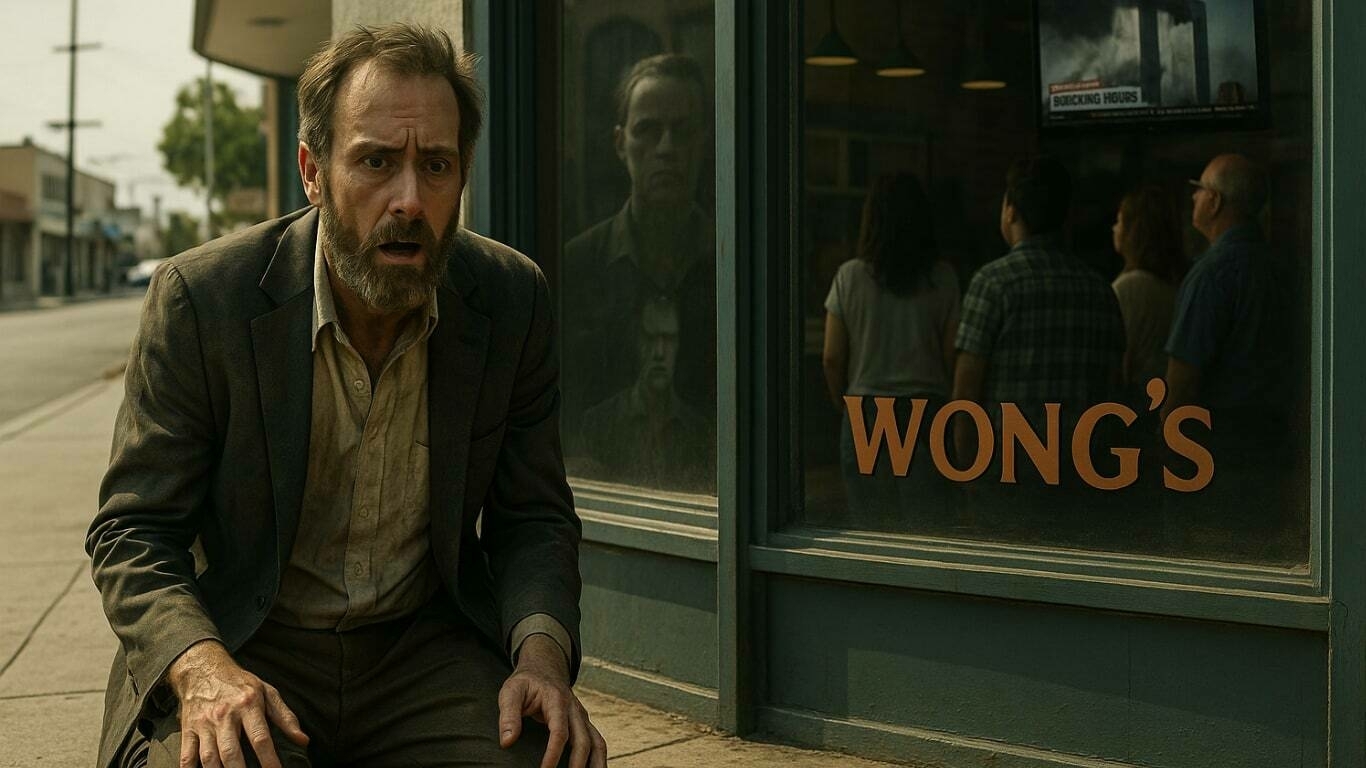

You remember when you first met Caruso.

The bar was low and narrow and stank of bleach and piss. You could miss it from the street if you weren’t looking for it, and no one ever was. Neon dead in the window. Dust on the bottles. The fan overhead spun slowly as if bored of the heat.

You sat at a booth in the back. Vinyl torn. Duct tape curling at the edges. You wore a suit that didn’t yet fit your name. Hair still neat. Tie still tight. Skin too clean for the room.

Bryce Wexley, City Council, Eighteenth District. Newly elected. Still shaking hands like they meant something.

And that was when he walked in.

Vince Caruso.

Thick in the shoulders. Heavy in the eyes. Shirt unbuttoned one past respectable. Hair slicked back but thinning in a way he pretended not to notice. He moved like a man who’d carried things in trunks. Heavy things. Wet things.

He didn’t sit. Just slid into the booth across from you like he owned the air between you.

He said nothing.

Just set a manila envelope on the table. His hand lingered there for a moment. Then left.

You looked down. You didn’t open it. Not yet.

No name. No seal. Just a faint thumbprint where someone had gripped it hard.

You knew without knowing.

Five grand. Untraceable. No memo. No contract. Just a small note, folded like a prayer: Remember your friends.

He lit a cigarette. Blew smoke toward the jukebox that hadn’t played in years.

“City Heights ain’t Washington,” he said finally, voice like gravel under boot.

“You’re goddamn right.” You told him.

He looked at you like he’d already seen the whole arc, beginning to end.

“You got the face for the cameras.” he said. “But you need to decide what kind of man you’re gonna be when they’re off.”

“I am rather photogenic, aren’t I?” you said. “But I already know exactly what kind of man I am.”

The choice had been made the moment you walked through the door.

Caruso rose. Left the cigarette burning in the tray. Never looked back.

You opened the envelope. You counted the money. The amount was a paltry sum. Laughable. You accrued more money through your family’s empire in the seconds it took you to count. You tucked the note into your inside pocket.

You carry it still. You never needed it. What you needed was Bryce. Someone to do your dirty work. He was beneath you, but that had its appeal, knowing your family would disapprove.

The next step was that night.

Late autumn, 1992.

Fog thick on the San Diego waterfront.

You were still a city councilman, not yet thirty.

Caruso was a mid-tier muscle for the Bravanti outfit—connected through labor unions and port security. A fixer. A messenger. And when needed, a cleaner.

A man named Tomas Reza—mid-level union accountant and federal informant—got cold feet. He contacted a local reporter with names and routing numbers and whispered rumors of City Hall connections. He’d been seen at three fundraisers. One hosted by your people. He had photographs.

Tomas Reza had to disappear. But no one wanted the blood on their hands. Not officially.

The call came in the night.

Caruso picked you up himself in a grey Ford with no plates. You didn’t speak much on the ride.

“He’s in the warehouse already. All you gotta do is help me bury the problem.” he says.

“‘Help?’ I’m here to make ensure the job gets done right. And I want him to know.”

The warehouse was condemned. Steel walls rusted to ash. Windows busted and patched with plywood. Somewhere, a freighter horn moaned in the fog.

Reza was bound, beaten, mouth taped. Eyes pleading. He recognized you. That was the best part. He made mouth noises behind the duct tape. You couldn’t make out what he said, but his message was clear: “Please don’t! Please Don’t kill me!”

It was quick. A length of cable. One pull.

Reza was the first man you had put down, and you knew there would be others in your future. You were more excited than ill. You had crossed a threshold.

Neither of you didn’t talk after that. Just worked. Just shoveled dirt into a makeshift grave cut into a gravel pit behind the warehouse, under a trapdoor in the concrete floor that Caruso said used to be part of a smuggling tunnel. After a few scoops you let Caruso do the rest of the work.

“It’s deep enough.” Cause said, wiping sweat from his brow with Reza’s tie. “We pour concrete next week. City’s paying for it. Funny world, huh?”

Caruso asked you to help move Reza’s body. You made a token effort, and then, after a few moments, you let Reza’s legs fall to the ground. Caruso glared at you but said nothing. He knew who held the leash.

Your shoes were ruined. You threw them in the bay later that night. You went home barefoot.

Neither of you spoke of it again. No names. No location.

Only “that thing down by the docks.”

The cover-up held. Reza vanished. The story died.

You rose in the polls.

Caruso moved up, too. Quietly. Doors opened. Favors exchanged.

But you both remembered.

Sunday, May 11, 2025

Get Right with God

Agent Nicholas Grayson. The dogs are barking. Down the street someone screams. High and broken like glass in the wind. It pulls you from the dark where you’d been dreaming. Some place black and wet. You lay there breathing. Your pants stick to you. Your cock slick with the last heat of it. The spillage cooling on your thighs. You do not move. You feel a fly crawling across your cheek, and you let it.

Then the smell comes. Old meat. Sweet and foul. You know it at once though you’d tried to forget. The bunkers. The silence beneath the earth. The heat and the bodies. What you found there. What you kept. You close your eyes but the dark only brings it closer.

You remember what came before. Before the war and the sand and the silence that followed. The day the recruiter came. The house The fan humming overhead and stirring the heat but not cooling it. The smell of coffee and dish soap. Early summer. Dust on the sill. Light slanting through the yellowed curtains.

The house is plain. Suburban. Brick with streaked siding and a porch that creaks in the heat. The lawn is cut to regulation height, edged sharp as a blade. You mow it not out of pride but discipline. A need for order. A ritual to keep the chaos at bay.

High school’s behind you. You’re still lean, all elbows and wire, but the body’s changing. You’ve taken to lifting. Running. Waking before the sun to train. Muscle and motion and meat. Steak, chicken, eggs. You eat like it’s war.

You’ve played ball—football, basketball—so you’ve got a base. But this is different. This is hunger turned inward. This is the grind. And it suits you.

He sits across from you in dress blues. Palms flat on the table. Like a man laying down cards. Staff Sergeant Clay Devlin. His eyes calm. Measuring. The kind of man who’d seen fire and never flinched from it. He speaks softly. Like a thing rehearsed. But not dishonest. Not quite.

“Ma’am, I know this ain’t easy. I get mothers in tears. Fathers who slam the door. That’s part of the job.” he says.

Your mother sits stiff-backed in her chair, hands in her lap, eyes never leaving the sergeant’s face. “Then maybe the job’s wrong.”

“Your son’s got something, ma’am. Discipline. Grit. I seen it the second he walked into my office. Most boys come in looking for glory or a way out. Nick—he just wanted purpose.”

“My son’s got purpose right here. This land. This family. Nicholas, why don’t you tell me what you told the officer here why you want to join the Marines?”

“I want a chance to serve my country and the Lord, fighting against the world’s evil.” You say. “I want to do something with my life. I want to be useful.”

“Nicholas, you’re such a smart boy. You don’t have to do this. There are so many other ways you can express your God-given talents. But your daddy was changed when he came back from the war. That’s when he started drinking, and that’s why he left us.”

She turns toward you, face flickering with pain.

“The uniform don’t know you. The flag ain’t gonna send you a letter when your body comes back zipped in a bag.”

“I have to do this,” you say. “I have to do something. You’ve told me my whole life, how much evil there is in the world. And we pray, we pray to the American flag, we pray to protect the president and the troops. And I’ve always known that that was something that called to me, and now I know it is what I’m supposed to do. I feel a calling, Mother.”

“Ma’am,” says Devlin with a gentle, practiced calm, “I’d be lying if I said it was safe. But I will tell you this: he’s got leadership potential. He’s smart. Observant. Steady under pressure. I don’t just want him in my Corps—I need men like him. Men who don’t flinch. He’ll be part of something that matters.”

“I already lost my husband to the bottle, Sergeant,” she says. ”My boy’s the last steady thing in this house.”

She stands. Walks to the sink. Her back to you. Her shoulder shake.

“Nicholas, you’re a grown man. Old enough to make your own decisions. I can’t stop you.”

She turns around and look you in the eye, and you see the pain etched on her face.

“Make sure whatever’s left of you comes back through that door one day.”

“I’ll come back to you, Mom.” You tell her.

“Ma’am, the Corps takes care of its own." Says Devlin.

Staff Sgt. Devlin turns to you. “Pickup’s Thursday. 0600 sharp.”

He nods to your mother again, respectfully.

Then he’s gone. Only the clink of the tap and the steady breathing of your mother trying not to cry.

“I’m gonna make you proud, Mom,” you say, “I’m gonna make you proud.”

You’re full of it. Hope. The real kind. The kind that hums in your bones and makes the world seem like it might open its arms instead of its teeth. For the first time you can remember, the path ahead doesn’t feel like a trap. There was a time you thought the only way to keep from falling into darkness was to put on the collar, become a priest, seal yourself off from the rot of the world.

But not now.

You suck in your gut and puff your chest. Try to look like a man. For her. To give your mother something to believe in. To ease that worry behind her eyes. It hurts to see her afraid. But you feel it in your bones—this moment. You’re strong. Invincible. She’s wrong. It’s not dangerous. Not for you.

You think of your dad.

He left when you and Marley were still small. Started fresh somewhere else. Remarried. Took in her kids. Younger than you by a stretch.

After he left, you and Marley did what you could, but it was your mother who carried the weight. Day in, day out. And though she never said it, the leaving broke something in her. Left it unfixed.

You were bitter for a time. Shut down. Quiet. But as the years passed you stepped up. Took on more. And this past year, you made your choice.

You enlisted. Marines. Not for escape, but for purpose.

Something clean. Something true.

Boot Camp, MCRD San Diego

Marine Corps Recruit Depot, San Diego. Summer 1990. Day 12 of training. 0430 hours.

The lights come on with the wrath of heaven. White and sudden and unkind. A trashcan lid clangs against the concrete like a bell calling the damned to reckon. You woke hard, breath shallow, heart kicking. Above you Whitaker mutters a curse thick with sleep.

“Rise and shine, you goddamn abortions! This ain’t your fucking mama’s sewing circle! This is the United States Marine Corps!” Barks the DI.

The squad bay erupts like a nest of stirred hornets. Cots groan. Flesh slaps tile. Your body moves before thought arrives—folding sheets, lacing boots, tucking your shirt. You did not speak. You did not look. You simply obey.

The floor stinks of mildew and old socks and the thousand-foot stink of boys not yet men. The ceiling fans turn above you like the rotors of ancient machines, carving time out of the dawnless dark. Outside the sun had not yet breached the wire, but sweat already silvers your brows like a baptism in a bloodless church of war.

You worry you won’t measure up. Not the worst in the platoon, but nowhere near the top. And you reckon you won’t rest easy till you are. You don’t know the others yet. There’s laughter, sure, but it’s the kind with teeth. The kind men use to test each other. All chest and shoulders and eyes that don’t blink. It wears on you.

Their language comes hard and constant. Profanity like breath. Like ritual. You’d heard cussing in high school, but not like this. Not like the flood of filth that fills the air here. Cocksucker. Motherfucker. Faggot. Cruelty braided together in jest. Shirts are called blouses. Toilet paper’s shit paper. Words twisted. Made crude. Familiar things made strange.

You were raised Seventh-day Adventist. Raised to mind your tongue. In high school, they left you alone for it. Gave you space. Not here. Here it’s everywhere. And now you try your hand at it. Swearing. Just to belong. The words come out awkward. Clumsy The others laugh. Elbows in ribs. Grins like blades. No harm yet. But you feel the edge.

They see you pray. Morning and night. Quiet and steady. A cross beneath your shirt, warmed by your skin. Some of them pray too. But not like you. Not with fire. Not with fear.

They’ve given you names—Preacher, Padre, Choir Boy. Words meant to belittle, but not to wound. Not yet.

You miss home. Miss your mother. There are moments you regret coming here. Real fear, cold and deep. But your body changes. Hardens. The boy you were begins to vanish. And what’s left, you don’t recognize. Not yet. But it’s coming.

They tell you to embrace The Suck–the Marine Corps and its daily misery. So you embrace it.

Obstacle Course – 0900 Hours

The course cuts through the base like a scar. Ropes, walls, sandpits, barbed wire—challenges carved from pain and repetition.

You pull yourself up a cargo net, arms burning. Beside you, Whittaker grunts and swears and laughs like the whole thing’s a joke.

“I swear, Nick,” he says, “if I survive this I’m gonna marry the first woman who brings me fried chicken and don’t ask no goddamn questions.”

“You’ll marry the first girl that kisses you.” You say.

You and Whittaker reach the top. From the far side of the course, Silas Mercer clears an obstacle without breaking stride. Efficient. Joyless. His face unreadable beneath the dust and sun.

Kelso lags behind. Cuts corners. Breathes through clenched teeth.

You and Whittaker are cut from different cloth. He’s loud. Loose. Laughs like a man who’s never known the weight of silence. You keep to yourself. Tight as wire. More at home with a page than with a punchline. And yet, somehow, you’re becoming friends. It could be the bunk assignments. It could be just circumstance. You’re different enough that you don’t have to pretend. There’s peace in that.

You like his lightness. The way he floats above things. It’s foreign to you, but you admire it. It makes you feel, in some quiet way, proud. Like you’ve reached across some divide. You think he’s trying to break you open, loosen you up. And maybe he’s right to try.

Mercer is something else. You’ve only known him a short while, but he carries the air of a man who’s seen too much or not enough. At first, you think there’s kinship. Same background, maybe. But the longer you’re near him, the less certain you become.

There’s something wrong beneath his skin. He’s distant, yes, but more than that—superiority. Like he’s above it all. Above you. You don’t think he came here for duty. You think he came here to kill. And not for cause. But for pleasure.

The others may be crude, loud, simple—but you can feel their hearts beating in their chests. Their souls, scuffed but intact. With Mercer, there’s only silence. Something cold. Like a man-shaped absence. Like whatever was meant to be human in him has packed up and left. Or died in place.

Chow Hall – 1230 Hours

The food is grey and flavorless. Eggs that bounce. Coffee that tastes like burnt rubber and battery acid.

You eat in silence. Mercer sits alone, always. Kelso goes to sit next to him, and Mercer just looks up at him with hose dead eyes of his, as if daring Kelso to sit. Kelso shrugs his shoulder and walks over to your table and sits across form you.

“Mercer watches people sleep. Did you know that?” asks Kelso.

“Well, we all can’t sleep.” You say. “It’s probably nothing.”

“I don’t know. Man, the way he looks at us, it’s like a fucking spider looking at its prey.” Says Kelso.

“I had that same thought at one point.” You say. “He does have way of looking at you, like he’s planning something, like he wants to eat your face.”

Across the room, Mercer smiles. Just slightly. Like he heard every word.

Whittaker talks as he shovels food into his mouth. “I hear there’s a circus in town. Marle Brothers Big Top. I shoulda joined the circus instead of the Corp. Food’s probably better.”

Whittaker is the yin to your yang. In the mess hall he pushes at the edges. Just enough to make you smile. When the sergeant’s back is turned he shapes faces in his food. Sometimes worse. Mashed potatoes molded into mockery. Peas for eyes. A crude cock and balls drawn with gravy like ink on a page. It’s stupid. And it’s perfect. In a place meant to grind you down, it feels like defiance. You feel it too. Like sin without the stain.

He leans over while you eat. “You gonna eat that?”

You open your mouth to answer but he’s already helped himself. Fork scraping your tray. You don’t stop him. Don’t even flinch. You let him take it. Long as he doesn’t touch the meatloaf.

Rifle Qualification – Day 24

You lay prone. Breath held. Sight steady.

The rifle is a language now. You speak it fluently. Your grouping is tight. Your posture perfect. The instructor nods once.

Next lane over, Mercer doesn’t miss. Not once. His score is perfect, but he shoots like he’s removing something from the world. Not practicing. Purging.

After qualification, Mercer approaches you for the first time. “You shoot clean.”

“Oh, well, you know, I’m just getting the hang of it.”you tell him. “You’re not a bad shot yourself there, Mercer.”

He doesn’t acknowledge the compliment. “You need to shoot fast.” He says. “You’ll need both.”

He walks off, and for a second you watch his back and think: that’s not a man—they just gave something shaped like one a uniform.

A thought’s been creeping in lately, one you don’t want to name. But the way Mercer moves, the way he looks at people—it’s like something else is in him. Something old. Something wrong. You used to think all that talk about the devil was just metaphor, or maybe you believed it but never expected to see it. Now you’re not so sure. He feels possessed.

Barracks – Night

The squad bay is quiet. Except Mercer, laughing in his sleep. Soft, muffled. Like a child dreaming of pulling wings from flies.

Whittaker whispers from above. “That motherfucker’s gonna shoot somebody who ain’t wearin’ a uniform one day.”

Outside, the wind rattles the flagpole. You stare at the ceiling and do not sleep.

The Desert

Forward Observation Post, near Al Khafji, Northern Saudi Arabia. Three days before the ground assault begins. The air is still. The world waits to crack.

The desert in February is cold before dawn and hot by midday, and cruel no matter the hour. The sand stings the eyes and clogs the throat, whispering over the dunes like a voice without language. Everything is the color of bone. Dull. Scoured. Forgotten.

You lay flat in a shallow fighting hole cut into a ridge of shale and sand. Your rifle cradled to your chest like an infant. The lens of your scope fogs slightly with each breath. You adjust without thinking. Movements slow. Smooth. You’ve been in-country long enough now that your hands know what to do before you do.

Beside you, twenty feet away, Boyd Whitaker hunkers down behind a berm, chewing sunflower seeds and scanning the horizon through binoculars.

“Ain’t nothin’ out here but God and the people he forgot.” Says Whittaker.

“I don’t know if God forgets anyone,” you say, “but they sure have joined the ranks of the unguided, lost misfit souls.”

Whittaker grins. “That’d be us, huh?”

“We do what we can.” You say.

You both fall quiet again.

Behind you, far to the west, the artillery boys are drinking warm water and telling lies to stay warm. Up front, it’s just them. Silence, sand, and radio static. A horizon so flat it feels like the edge of the world.

In the Sandbox, they gave you a rifle and made you a sniper. Whitaker beside you as your spotter, laughing even when there was nothing to laugh about. Mercer had the same assignment, and Kelso his reluctant spotter.

As a boy you’d held rifles in your hands, your father beside you in the scrub fields behind the house. But they never sat right in your palms. Cold and alien.

The M40 is different. It speaks to you. There is a cleanness to it. A discipline. You strip it down, part by part, and learn its language. Steel and spring and breath. A thing that holds death like a secret and gives it shape.

When you shoot, you pray. Not loud. Not for show.

“Lord Jesus, God, bless this bullet.” You say.

Or, “Still my breath. Steady my hand. Let this be Your will.”

Each trigger squeeze a prayer. Each round a rosary bead. And in the scope, justice comes in small and distant shapes. And you are its vessel.

You carry your phrasebook like scripture, dog-eared and damp with sweat. As-salaamu alaikum. You say it under your breath, again and again. Peace be upon you. The words settle in your mouth like dry bread. You whisper them before you shoot. A prayer of precision. Peace by way of fire.

The Quran you keep hidden. An English translation tucked in the jacket of your Arabic manual. You study it in secret. You’re drawn to the washings, the prayers, the aching beauty of the mosques and the voices rising from minarets. There’s order in it. Cleanliness. Discipline. You admire it the way you might admire a distant star. Bright, unreachable.

But the words don’t speak to you. Not the way your own do. The text is dry. Hard. Full of rules. The tone cold. And yet the names of God comfort you. The reverence. You like how they speak the Prophet’s name with care. Peace be upon him. Always.

You haven’t bathed in a week. You drink water like a man dying but never feel clean. Your body is covered in dust and sweat and grease. The stink clings to you. You no longer notice it on yourself, only in the others. You watch the locals and envy their purity. Their white garments. Their rituals of water.