Operation Watchtower | Chapter Two: Tough Talk

Wexcess

Bryce Wexley. You drag the back of your hand across your mouth, the bile sour on your tongue, and through the fog of sweat and heat and shame you see him—Wong. Framed in the glass door of his diner. His eyes dart up from you to the television behind him where the towers burn. Then back to you.

Wong comes upon you slow and sure, like a man approaching something wounded. His face, it creases not in pity but in the quiet knowledge of pain. He holds out his hand. “Let’s get you inside.”

You raise your eyes and for one moment, his head is engulfed in a dandelion of golden radiance. A crown of fire, wild and tender. You blink. It is gone.

He guides you to a table. “I get you something to eat. Something to settle your stomach.”

You hear your name like it’s been dragged out of a well. Takes a second to realize it’s coming from the TV. You look up, and there you are. Sitting next to Phil Doherty on Tough Talk. That grin of his plastered on like always. Only this isn’t a rerun. It’s live. Now.

And the man sitting beside him—it’s you. But it isn’t.

The man on screen sat straight-backed and sure. He was what you strive to be. What the press hinted you might become. You watch him, that other you, and you feel like you are peeling away. Like he’s shedding you, leaving the husk behind.

Your first thought is that the man on the screen is not a man at all. That he’s a skinwalker, a lizard wrapped in meat, some reptile thing done up in your own hide like a suit bought cheap and ill-fitting. It’s wearing you. Wearing your smile, your gestures, the way you hold your hands just so, like they taught you in the greenrooms.

But it doesn’t make sense. If the skin’s enough, why would they need yours? And yet you watch and you feel it all the same—the shame, deep and black. Your hair stuck flat to your skull with sweat and bile, your clothes a patchwork of filth, your feet raw. And there he is, sharp as a blade, suit pressed, hair combed, the world leaning toward him like flowers to the sun.

Your voice rises from your throat like something choking. “That isn’t me! They replaced me!”

A patron two stools down lifts a finger slow to their lips, eyes sharp over it. “Shhh!”

“Good morning, folks.” Says the television host, “I’m Phil Doherty, and this is Tough Talk. Now listen, I wish we were kicking things off with something a little lighter today, maybe even a little fun. We’ve got Senator Bryce Wexley here with us—yes, that Wexley. His family’s been called the Kennedys of the West Coast. A real political dynasty. And Senator, we appreciate you being here.”

“Thanks, Phil.” The other Bryce says, “It’s a pleasure to be here, as always. And I’ve got to say, nice suit.”

Phil laughs, then turns to look directly into the camera.

“But let’s be honest—we’ve got more pressing business this morning. America is under attack. So we’re going to put your reality show segment, Wexcess, on hold and focus where we need to: the safety of our nation and the facts as we know them. This is no time for fluff.”

Behind the host and the man wearing your face the screens play clips from Wexcess. They’ve stacked the deck for spectacle. The old producers knew their craft. Knew how to gild the rot.

There you are, barreling down some desert highway in that gaudy Humvee like a king of nothing, the sun burnished on chrome and steel. Cut to you again, poolside, flanked by supermodels whose names you never learned, their laughter canned and hollow.

The reel rolls on. Red carpet, flashbulbs, the dumb applause of a thousand strangers. You grinning like a man with no past. No blood on his hands.

Then your boy, Graham. His face lit and sharp. Telling the camera during a talking head segment how you “suck,” and there’s you right after, telling the world Graham’s “very, very sorry for what he said.”

All of it stitched together like some gospel for fools. You watch and you know it’s a lie. But you can’t look away.

Doherty turns to the camera. “Stay with us. Tough Talk returns after these messages.”

And then a commercial plays, some inane morality play of capitalism. A family at breakfast, their smiles carved and hollow, praising a thing they did not make and do not need.

Wong comes back bearing the plain grace of hot food. A chipped plate. Scrambled eggs. Toast browned and crisp at the edge. Steam rising from the coffee. He sets it down.

“You want jelly?”

He doesn’t wait for an answer. Just smiles that quiet smile of his and lays a packet by your plate. Then he turns and goes.

He doesn’t know you from Adam. doesn’t know the office you hold or the fortune you command. To him you’re just another vagabond off the street.

And still he brought you breakfast. He treats you with dignity and kindness.

You tear the packet open with trembling fingers, the foil splitting like skin, and squeeze the jelly straight to your tongue. It coats your throat sweet and cheap and chemical. You drag the eggs into your mouth like a man starved, which you are, and the toast follows in great wet mouthfuls. The food hits you like morphine. Your hands shake. Your heart beats fast and light.

You look up, eyes flicking sharp like a hunted thing. What’s his angle, this Wong? Man feeds strays, but why? You’ve seen enough to know nothing comes without a hook. You saw his head glow. Maybe he’s one of them. One of the good ones, maybe. The kind who wears a man’s shape to pass in the daylight.

You think about that radio show, late nights in the dark, Art Bell talking about The Greys, the Reptilians, the ones who made the deals. Maybe the things you saw in Alpine—maybe they were real. And maybe Wong’s not like them. Maybe he’s something else.

You glance sideways. Real careful. Check your hands. Your mouth. You listening to yourself now, the words running under your breath without your leave. You wonder if anyone’s watching.

And the worst thing is you know they are.

After the meal Wong comes and takes your plate without a word and wipes the table clean with a rag drawn from the pocket of his apron. He looks at you once.

“Come with me.”

You follow him cautious as a coyote, ready to bolt should the air shift wrong. Your eyes fix on the back of his skull, the smooth dome of it shining faint under the fluorescent light, and you watch for some tell, some hidden seam in the meat of him where the zipper might run, where the mask might peel away and show the thing beneath.

At the front door a mop waits, its head limp and soaked in gray suds. Beside it a bucket, the water inside warm and soapy.

“You clean up,” he says.

You kneel at the bucket like a penitent and dip your hands into the murk, the water warm and citrusy with soap. You bring it to your face and scrub, the suds running down your neck, the sting of it in your eyes, the scent sharp in your nose. You wash as if you might scour something from yourself that the years have left behind. Something that clings. Something that will not come clean.

“No, no.” he says, “You clean up.” He points to your puddle of vomit. The scent of it rises and stings your eyes.

You let out a long breath. You roll your shoulders like a man shouldering a yoke and set to the work. The mop clumsy in your hands, foreign. You drag it across the floor in fits and starts. You move without rhythm, without grace. You reckon you’ve never done a day’s mopping in your life. But you do it anyway. Because there’s nothing else to be done.

And then you see him.

Not straight on. Just a flicker in the corner of your eye. He leans against a wall leading to an alleyway, smoking a cigarette. Watching. He draws on the cigarette slow and easy and flicks it into the street. Its cherry arcs through the air like a meteor before it hits the Earth, and the man turns and walks away.

Down the alley.

You follow his path with your eyes. You see where he goes. You know this street. You know every corner of it. You’ve walked it a hundred times and never once has there been an alley there. Not till now.

The mouth of the alley darkens behind the man’s retreat, swallowing light like a thing alive. Not shadow but absence. A void. As if God himself had turned his gaze from that place and would not look again. You come to the threshold where morning ends. The edge of light. You lift your foot. The air beyond is cold. Frigid.

You place your foot within.

And you know. In your bones. In the red meat of you. One more step, and there is no turning back.

You are not a fool. You turn from the alley and make your way back to the diner, to your mop. You mutter low beneath your breath of dissection tables and cold steel and how wise a man is who knows when to run.

Slyly, you look back at the alley through the tangle of your hair. The alley gone now like it never was. Like the world itself rolled over and smoothed the crease. But there on the pavement, you see it. The cigarette butt still smoldering. Smoke curling thin into the morning air.

Heat

Belle Flower. You’ve been standing in front of the Mira Mesa Public Library so long the shape of you is near worn into the concrete. The sun climbs higher. The shade crawls back. You keep expecting the man in the grey suit to round the corner, to step out from behind the world like he was always part of it. Instead you see the old ones walking. Old Chinese couples bent like river reeds, moving slow through the morning. Filipina mothers pushing strollers heavy with sleeping children. Indian women in their saris speaking low and fast, talking about the towers. The fire. The day the sky came down.

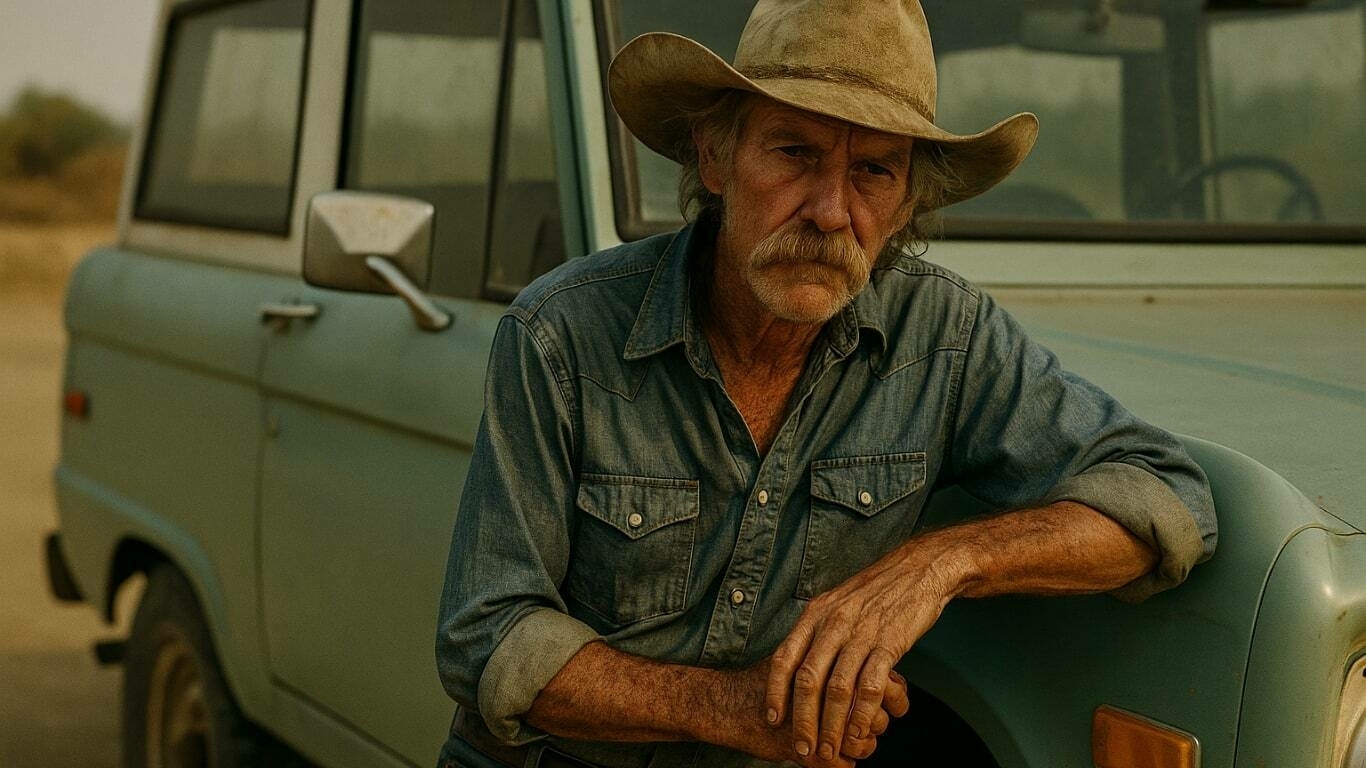

Red pulls up in his Ford Bronco, paint the color of faded jade, light catching on the metal like water in a dry place. It looked new. Lovingly restored. But the man behind the wheel was not new. Not untouched.

Red had lines now, deep and mean. His eyes sunk further in, not cruel, but tired. You remember them clear—sharp once, reckless. A man with miles ahead. Now he wears them all on his face. The years rode him hard. Drove deep. Didn’t let up.

Back then, he was all grin and boot leather. Hair long, engine louder than his conscience. He’d smoked through half a pack before you cleared county lines. Said little. Drove fast. Didn’t ask questions. The kind of kindness you don’t know you need until long after it’s gone.

He leans there against the Bronco, one arm slung careless over the doorframe. He pulls off his aviators slow and squints at you, his eyes pale and run through with age. He takes in the mess of you—hair wild, shirt twisted, sweatpants stained through, bare feet cut and streaked with road-grime and blood.

“Aw, hell. Get in.”

You tell Red about the man in the grey suit. How he killed your doorman and broke into your apartment like he owned the place, and how you escaped, dove through the window, and landed on the hedge like an animal in flight. You tell him you need to go back. Circle the block a few times, make sure the wolf is gone. Maybe get your hands on what’s left—your gear, your papers, a change of clothes. Whatever scraps of your life he didn’t take.

He lights a cigarette, draws on it. Smoke curls from his mouth, drifts past the scar in his lip. He doesn’t look at you, not at first. Just stares out over the parking lot.

“Buck did say you’re in some kind of trouble. Trouble seems to find you, don’t it?”

“I guess so,” you say.

He taps ash to the pavement. Takes another drag, and then you drive away.

Red turns on the radio, twists the dial and the voice comes raw through the static. Another plane has gone down. United Airlines. Flight 93. Crashed 80 miles southeast of Pittsburgh.

He listens a moment. Just a moment. Then he kills the radio with a flick of his fingers and silence folds in.

“Christ. Can you believe this shit? Whole goddamn world’s goin’ to hell. I swear, every time you think we’ve seen the worst of it, somethin’ new comes crawlin’ outta the pit.”

You let the breath leave you slow like something wounded. Say nothing. Your eyes fix on the window and the world beyond it, the sun climbing indifferent over rooftops and powerlines. You will not meet Red’s gaze. You try not to think about the news burning through the radio. There’s too much stirring in you. Too much weight. Like you been sleepwalking and the dream’s caught up to you. And worse than the dream is the knowing you helped bring it to life.

He glances at you and whatever he saw on your face made the words die in his mouth. Like a man realizing too late he’s been talking to a corpse.

“Thunderation, ain’t my place to talk about the end of the world when you look like you’ve been livin’ in it.”

He drums his fingers once on the steering wheel, then scratches at the back of his neck.

“Truth is, I shoulda kept closer, Belle. I shoulda checked in. Stayed on top of you, made sure you weren’t driftin’ too far out. But I didn’t. Life’s got a way of slippin’ past when you ain’t lookin’. Next thing you know, it’s been years.

“So tell me, kiddo. What’s it been like? What you been up to, besides runnin’ from shadows?”

“I’ve just been making it work.” You tell him. “I haven’t had a proper job. I haven’t been able to land any. Things outside of the circus. I mean, I’m not trained to do any of the stuff that normal people do, so I done what I could. It’s not very easy, but I do what I can. Nothing worth telling. Just enough to make it work.”

“You know, you ain’t grown an inch since I last laid eyes on you. But hell, I can see plain as day you’ve grown in ways that matter. You ain’t that scared little doe I hauled across state lines in the dead of night. Back then you looked like a thing that’d bolt if I so much as breathed too loud. Like the world itself was hunting you."

He flicks his cigarette out the window, watches the spark vanish behind him.

“I never asked what you were runnin’ from. Didn’t need to. I saw enough in your eyes to know it was bad. Knew it had your folks’ stink all over it. But you’re different now. There’s steel in you. Might not see it when you look in the mirror, but I see it clear as day. You been carryin’ yourself like someone who’s seen what’s on the other side of fear and decided she wasn’t gonna bow to it.”

He clears his throat, thumb tapping the wheel.

“And look, I ain’t your preacher and I sure as hell ain’t your daddy. But on a day like this—might be worth pickin’ up the phone. Callin’ your mom and dad. Even if it’s just to say you’re still breathin’. World’s comin’ apart at the seams, Belle. Ain’t no shame in lettin’ people know you’re still standin’ in it.”

He grabs his flip phone from the pocket of the shirt and tosses it on your lap.

“Your call. Ha, see what I did there?”

“Yeah,” you say, absolutely not. I have no plans to talk to them. I definitely don’t need them knowing where I am right now, so I hear what you’re saying, but it’s not something I’m comfortable with doing now.”

He sighs. “It’s a free country.”

As the Bronco rounds the corner you see police cruisers stacked four deep, strobes painting the stucco in blood and bruise. Radios crackle. Men in uniforms bustle about.

Red slows the truck. The engine idles rough beneath his calloused hand.

“That’s a lot of heat,” he says.

He turns to you then, eyes narrowed.

“Anything you need to tell me, kiddo?”

“I didn’t do anything wrong! I gotta go inside. And if the police are here, that means that most likely no one else is gonna try to hurt me. So maybe this is a good thing?”

You set your hand on the latch and you pause. Old lessons stitched into your bones like scars. Don’t talk to the law. Don’t let them know your name. You glance down at yourself—barefoot, bleeding, sweatpants fouled. You can’t be seen like this. Not here. Not now. Not with a man dead on the pavement. You let the door click shut and sit there in the heat. Waiting. Watching.

“Park down the block. I need to think this through.”

Red eases the Bronco down to a crawl and without a word he reaches across and shoves you low, one hard hand on the crown of your head, pressing you beneath the dash like he’s hiding contraband. His eyes never leave the road. His mouth set in a line you’ve seen before, a man weighing the cost of something already spent.

“Stay down!” he hisses

“What do you see?”

“Black sedan. I don’t know if they’re cops or not, but they’re definitely law. Guy in the passenger seat looks smart. I think he’s lookin’ for someone. Maybe you, Belle.”

“Gosh, Red, I don’t know what these people want from me! We gotta get out of here then, because this is not good. We gotta go somewhere else.”

“I can take you to my trailer back in Convoy. I got some clean sweat pants and some flip-flops you can wear.”

“All right. Let’s just go to your trailer. Let me sit down. Let me think for a little bit, because this situation’s not safe!”

Bronco

Nicholas Grayson. The plane touches down heavy as a stone on the tarmac, tires screaming beneath the weight of steel. The sky above San Diego blue and unbothered, indifferent to the smoke twisting halfway across the country. You’d been aloft when the first tower fell. Somewhere over Arizona when the second burned.

By the time the word of the Pentagon hit the cabin, it was no longer accident, no longer madness or malfunction. It was war. And every passenger knew it.

The plane docks. There is the slow, somber shuffle of feet, as if you were all walking from one funeral to another.

The badge you carry got you off quicker than most.

The terminal was chaos made flesh. Faces upturned to televisions, mouths slack and eyes burning, herded like cattle by staff who knew nothing and could say even less. You could feel the static charge of grief and terror in the air, a nation realizing it was not untouchable, that something had reached across the oceans and slit its throat.

Then you see him. A man in a suit, holding a placard: GRAYSON in block letters. His shoulders are slumped, his face pale and pinched and hollow-eyed, like someone who’d rather be anywhere but here. A man wanting nothing more than to be home, wherever home was, with the people he loves.

You walk up. Show him your badge. Tell him your name.

He tucks the placard beneath his arm and offers his hand, the shake firm but not unkind.

“Guthrie. Andrew Guthrie. Wish we’d met on a better day. This way.”

He nods toward the parking structure, and you fall in step beside him, the tide of bodies pressing in close all around. People moving like cattle through a chute.

“Can I take your bag?”

“That’s okay. I’ll hold on to it. Thanks, though, Mr. Guthrie”

Something gnaws at you. You slow your pace, your eyes lifting toward the open sky. Empty. Silent. No engines droning in descent.

Guthrie follows your gaze and answers without being asked.

“U.S. airspace shut down soon as the second plane hit. Grounded everything.”

You reach his car. A government sedan, black and anonymous. You slide into the passenger seat.

Guthrie starts the engine, glancing at you sidelong.

“Most agents, they want a minute. Get their bearings. Maybe sleep off the flight. But I read your file. Hell, you’re that Agent Grayson, aren’t you? Reckon you’ll want to get to it. Where to?” Guthrie’s eyes are fixed forward, hands on the wheel at ten and two.

“Miramar. Magnolia Village. Apartment building. I need to have a chat with a Miss Belle Flower.”

You give Guthrie the address and watch him nod once, slow and sure. Then you fish the Blackberry from your pocket, the plastic slick beneath your thumb. You dial your sister’s number without thinking. She picks up on the first ring. You hear her television in the background. News about the World Trade Center. The Pentagon.

“Nick? Oh, thank God. I can’t believe what’s happening! They’re saying it’s terrorists! Do you know anything about it?”

“Not a thing. I just wanted to make sure everybody was okay. I needed to hear your voice. How’s Pete?”

You reckon her husband’s decent as men go though you’ve long thought him touched in the head. A fool maybe but not the kind that means harm. Just a man who don’t know near as much as he thinks he does.

“Oh, you know, Pete. His lawn care business is taking off, but he can’t get his head in the game today. He’s coming home, which is for the best”

“That’s good. Okay, I’ve got to go. Stay safe”

“All right. Well, thanks for calling. You take care of yourself. Love you.”

“Love you, too, Marley.”

Just as you hang up, your BlackBerry pulses and you thumb the screen, and it’s a message from Alicia Hightower, the shrink the bureau paid for. It reads “I’m here to talk if you need me.”

You text back, “Thanks.”

You’re about to slip the thing back in your pocket when it comes to life buzzing in your hand. You look and the number is one you know. Boyd Whitaker. Fellow jarhead. You pulled each other out of the sand more than once in the war. You owe him more than you ever said aloud.

“Boyd, how you doing?”

“Hey there, good buddy. Heard you got yourself transferred. New division, huh? Only good news I heard all damn day. Hell of a day for good news, though, ain’t it? Where you hanging your hat?”

“Well, actually, right now I’m down in San Diego. How’s the life up in Los Angeles?”

“Oh, you know, walking and talking. Working the beat. San Diego? Huh? That don’t beat all. Do you remember Silas?”

“Silas?”

You close your eyes. Of course you remember. Silas Mercer. The man with the dead eyes. The one who liked the work too much. How he slipped through the cracks, past the shrinks and the tests and the red flags—that’s a question you stopped asking long ago.

“Always had a weird feeling about that guy, but then I also had the same feeling about Tim McVeigh. We all know what happened there. Seems like I should listen to those feelings.”

“Word around the campfire is, he’s been seen in San Diego. Few days back. Don’t know if that’s why you’re out there. God, I hope not. He’s a bad hombre, brother. Bad all the way down.”

“Yeah, he was a cold motherfucker.”

“Hey, something just hit my desk. I gotta run. Hang ten, brother. I’ll make my way down to San Diego. And if I can’t, come up to L.A., as long as you’re in town.”

“All right, buddy, good to hear your voice. Give a hug to the wife.”

He laughs. “Copy that.”

You arrive at Belle Flower’s apartment building. The flash of blue and red lights turning the stucco walls into a crime scene mural. Four squad cars. Officers milling at the entrance. One of them bent low beside a shape slumped against the pavement, a black tarp folded neat over what had once been a man. A forensic photographer crouched, camera raised.

You knew the shape of it. The stink of death in the air like something bitter under the tongue. You’d seen it before.

“Agent Guthrie, can you circle the block once? I want to get the lay of the land. Maybe see if Miss Flower is out and about. Keep your eyes open.”

You make your circuit slow and watchful, eyes scanning the crowd for a sign of Flower but she isn’t there. What you do see is a man behind the wheel of a light jade Bronco, the paint near luminous in the sun like something freshly minted. He’s got a cowboy hat stained from years of weather and sweat, aviators low on his nose, a cigarette burning down to the filter in his fingers. He looks like Sam Elliott if Sam Elliott had seen the bottom of a needle more times than a whiskey glass.

You pull into the driveway of Flower’s apartment building. And then you see it. Small and green and mean as sin. A fly crawling the length of the dashboard like it owns the world. Its legs tapping out some measure older than speech. It pauses a moment, its wings shivering in the stillness, and when you crack the door it slips past you into the wide and waiting air. Gone like it was never there at all.

You cross the lot and the officers watch you come like men waiting on bad news. One of them steps forward. Lean and hard-eyed. He looks you over, your suit, your shoes. The weight you carry.

“You murder police?”

“No, sir. Nicholas Grayson. I’m with the Bureau. FBI. Lookout division. I’m not here to cause a scene. Just trying to locate a particular individual listed at this address.” You lift the badge from your coat and hold it where the officer can see. It catches the light. “I’m looking for a young woman. Name’s Belle Flower. Early twenties. Possible connection to an ongoing investigation.”

He looks at you a long moment. Then he turns to the officer beside him, something passing between them that needed no words.

“All right, let me bring you up to speed. Victim’s Harold Nguyen, works the door here—lived on-site.”

He looks to the body shrouded in the black tarp at your feet.

“C.O.D.’s a single G.S.W. to the head, close range. Time of death logged at approximately 0602 hours. We’ve got that timestamp off a voicemail he left for one Belle Flower—tenant in Unit 2B. Nguyen was on the line with her when the shot went off. Suspect made forced entry into Flower’s unit shortly after. Timeline puts him inside within minutes. Flower either bailed out or was forced out of a second-story window."

The officer points to an open window, and then to smashed shrubbery below.

“Witness reports the perp circled back to the apartment after the fact, cleaned house. Took hardware—laptop, portable drives, could be intel, could be leverage. Description’s solid: Male, mid-30s, shaved head, facial hair—goatee. Dressed like a pro, grey business suit, well-built frame. Neighbor clocks him moving with purpose. No hesitation. Tires on Flower’s vehicle were punctured. Whoever this guy is, he came prepared. Knew the layout. Knew the timeline. Wasn’t here for the doorman. He was after Flower. Question is—why?”

The officer’s mouth is still moving when your eyes cut past him, drawn to the jade glint of the Bronco tearing off down the street like a beast loosed from its pen. You don’t hear the rest of what he says. You already know.

“All right,” you mutter, voice flat as the asphalt. “Thank you, officer.”

You slide a card from your coat, hand it to him without looking. “Keep me looped in. Any contact with the young woman, I want to know.”

Then you’re moving, the pavement underfoot, the blood in your ears. You throw yourself back into the sedan.

“Guthrie,” you bark, slamming the door. “we’ve got movement. Follow that Bronco!”