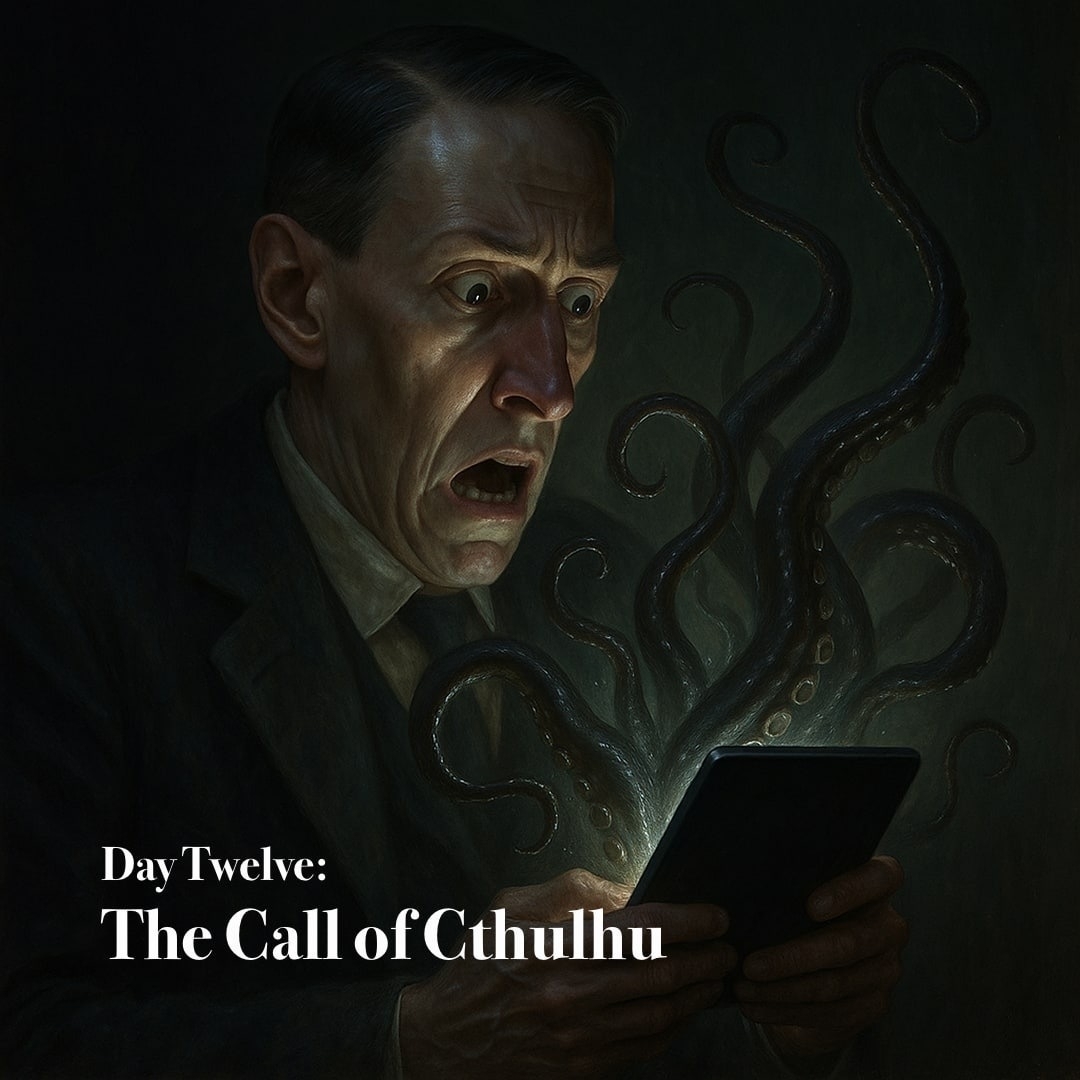

The Call of Cthulhu

When at length I resumed my custom of reading one tale each October day from the dread canon of H. P. Lovecraft, I found myself possessed by a curious and most unsettling revelation. Those works of vast and monstrous scope, for which he is chiefly remembered among the disciples of horror, stirred within me little of the awe they once did. Instead, I discovered a growing fondness for his tales of a more traditional and spectral nature, those haunted by the chill breath of the supernatural rather than the vast indifference of the cosmos.

After much brooding upon this strange preference, I discerned a reason for it. By the time my own eyes first beheld Lovecraft’s prose, his influence had long since bled into the arteries of popular culture, permeating it like a contagion that none could name. The dread he had once called forth from the abyss had become the common inheritance of storytellers. His vision, perhaps, had been refined, its terrors rendered more immediate to the modern imagination. He may indeed have expressed, in his age, the truest form of comic horror, yet the figures that wander through his stories are, for the most part, pale and bloodless shadows, scholars and dreamers without the pulse of the living.

It was left to others, such as the comic book writer Len Wein and the director John Carpenter, to shape that same grotesque humor into something more personal, more visceral, and, in their way, more alive. In Swamp Thing and The Thing, one may sense the restless ghost of Lovecraft’s imagination, transfigured into forms that breathe and decay before our eyes.

Thus, I find myself drawn more to tales such as “Cool Air” and “The Rats in the Walls” than to “The Call of Cthulhu”, though the latter stands as the great monument of his name. Yet even within that most famous chronicle lies, in its opening lines, the purest expression of cosmic dread ever to pass through his pen:

The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents. We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far. The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the deadly light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.

There, within those sentences, lies the cold marrow of Lovecraft’s terror: that knowledge itself is the forbidden gate through which sanity perishes.

And now, having dwelt too long in the shadows of that terrible wisdom, I depart to witness a gentler spectacle. My grandson’s Little League team plays this afternoon, and they are said to be on a fine winning streak. Perhaps today they shall claim their sixth triumph beneath a sky that, mercifully, conceals whatever lurks beyond.

Now, let’s discuss today’s tale.

From beyond the shroud of mortality, Francis Wayland Thurston sets down his testament, a grim bequest of knowledge inherited from his late grand-uncle, Professor George Angell of Brown University. Among Angell’s papers lay strange and terrible proofs: a bas-relief wrought by the trembling hand of artist Henry Wilcox, whose fevered dreams were peopled with vast Cyclopean cities and sky-flung monoliths; reports of unholy rites and mass hysteria across the globe; and the testimony of Inspector Legrasse, who in 1907 shattered a swamp cult steeped in blood sacrifice. Their idol, fashioned of green-black stone, was the very twin of Wilcox’s accursed carving, and the cultists named it Cthulhu, one of the “Great Old Ones.” That Esquimaux tribes on the polar rim muttered the same blasphemies bespoke a worldwide, immemorial covenant.

Thurston’s inquiry led him to the journal of Gustaf Johansen, survivor of the derelict Alert. The sailor’s account revealed the unspeakable: the rising of nightmare R’lyeh from the abyss, its angles affronting human geometry, its vaults disgorging the thing whose name shudders through human legend. Johansen and his crew had loosed Cthulhu, who strode forth to claim them. In terror they fled; Johansen alone lived long enough to tell of ramming the monster with his vessel, a futile gesture that scattered but did not slay. Soon after, he perished under sinister circumstance, as if the cult’s reach spanned oceans.

Thus Thurston, piecing together dream, idol, journal, and death, discerned the dire truth: that Cthulhu, though chained in slumber, stirs restlessly in his drowned crypt, and that men, in their ignorance, stand ever upon the brink of his return.

“The Call of Cthulhu” itself was born of a dream Lovecraft suffered in 1919, later nourished by the deep roots of Poe, Maupassant, Machen, Dunsany, Merritt, and Wells. A tremor in Quebec in 1925 may have lent it its seismic note. Rejected at first by Weird Tales, it found print in 1928, and though Lovecraft judged it “middling,” others knew its magnitude. Robert E. Howard proclaimed it a masterpiece, Peter Cannon hailed its cosmic terror, and Houellebecq named it the first of Lovecraft’s “great texts.” Scholars in later ages discern even the echo of warped spacetime in Johansen’s visions. Today it endures as a black monument to the utter insignificance of man beneath the gaze of powers vast, alien, and eternal.