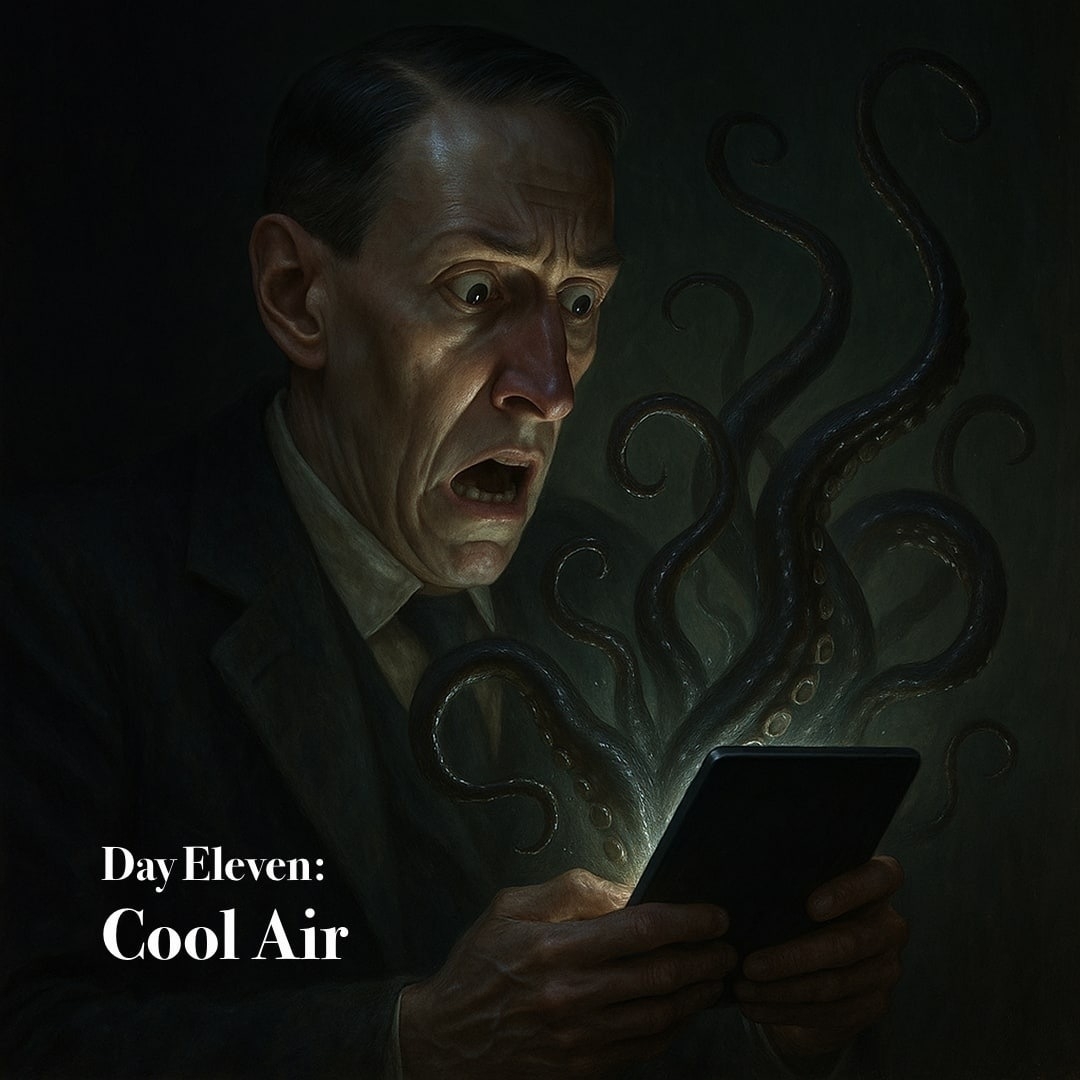

Cool Air

Though I hold in reverence the vast immensities of cosmic horror, it is not within that infinite void that my deepest affections for H. P. Lovecraft reside. Rather, two tales of more intimate dread, “The Rats in the Walls” and that frost-laden vision, “Cool Air,” I treasure above all, for they whisper not of gulfs between the stars, but of corruption festering close at hand, within the walls we build and the chambers we inhabit.

It was within the pages of Warren Publishing’s Eerie that I first encountered “Cool Air,” brought forth in ghastly splendor by the pen of Bernie Wrightson. The tale itself chills the marrow, yet Wrightson’s art breathed upon it a grotesque vitality, searing its images into my brain as though etched with acid. So potent was this encounter that I was lured, with the added enticement of Michael Whelan’s spectral cover, to purchase The Best of H. P. Lovecraft: Bloodcurdling Tales of Horror and the Macabre. Imagine, then, my despair upon discovering that “Cool Air” was absent from its pages. Yet by that moment, the abyss had already claimed me. The seed of Lovecraftian devotion had sprouted, and my love for his sombre genius had taken root, never to be torn away. Indeed, I have recounted this blood-stained chronicle to my grandson, though I was compelled to strip it of its darker enormities, softening its horrors until they might pass gently into the mind of one so young. Yet even in that gentler form, I fear some echo of its dread may have lingered, whispering faintly in the secret chambers of his dreams.

Our narrator recoils from the merest breath of chill, for in that faint draught lies the memory of horrors unspeakable. It was in the year 1923, when, in his search for lodging amidst the labyrinth of New York, he came upon a brownstone on West Fourteenth Street. There a leaking effluvium betrayed the presence of the tenant above me, Dr. Muñoz, a recluse of prodigious skill in medicine and stranger habits still. When death’s icy hand clutched at his heart, it was Dr. Muñoz who restored him, and thus began a companionship both fascinating and dread.

Yet with each passing month the truth of his obsession unveiled itself. Dr. Muñoz’s chambers, ever chilled by infernal engines and ammonia coils, lay at a constant 56 degrees, often sinking below the freezing point. He lived only in the embrace of cold, and the more his health waned, the more he labored to hold back decay with science that verged upon sorcery. When at last his pumps failed, he shrieked for ice, imploring our narrator to heap it round his body in tubs and crates. He scoured the streets for supply, but the effort was vain. When mechanics came to mend the machine, they found only corruption, for Muñoz’s body had burst into putrescence, and a smeared missive told the ghastly truth. He had been dead for eighteen years, sustained in mockery of nature by frost and drugs, a revenant of his own unholy craft. From that day forward, the faintest draft of cold air has borne for our narrator the stench of his doom.

This tale, “Cool Air”, Lovecraft wrought during his banishment in New York, when alien streets and oppressive crowds weighed upon his spirit. Critics discern in it his loathing of that city, a reflection of the jarring opposites between his cherished relics of New England and the clamorous multitudes of Red Hook. Its setting was drawn from a townhouse at 317 West Fourteenth Street; its maladies echoed the heart afflictions of Frank Belknap Long, and its chill mirrored Lovecraft’s own frailty. In its conception there stir the shades of Poe’s “The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar” and Machen’s “The Novel of the White Powder.” Though Weird Tales cast it aside, later voices proclaimed it among his most potent New York visions, an understated horror, subtle yet enduring, wrought in the cadence of frost and death.