I woke up from a dream with the “Hokey Pokey” rattling in my head. Huh.

Finally, finally, FINALLY watched The Wicker Man. Utterly delightful. I didn’t expect it to be a horror movie and a musical!

I’ve only had my Kobo Clara Colour for a day, but I like it. It’s smaller than my Kindle Paperwhite, but that’s good. It’s easier to put in my back pocket or sling bag. On the downside, I’m unable to export my highlights. I’m hoping to find a solution that doesn’t involve using Readwise.

I’ve never seen a decent adaptation of H.P. Lovecraft’s stories, but this one is pretty good. And with Nicholas Cage, no less. Guys in the middle of his horror renaissance.

I would sure appreciate it of someone would help me pin a post to the top of one of my Micro.Blogs.

I am this close 🤌 to purchasing a Kobo Clara. Anything I should know or thoughts on the Clara Colour before I tap the purchase button? Thanks!

10 minutes in to Random Number Generator Horror Podcast‘s review of this flick I hit pause and had to watch this movie.

Finished reading: Jung’s Seminar on Nietzsche’s Zarathustra by James L. Jarrett 📚

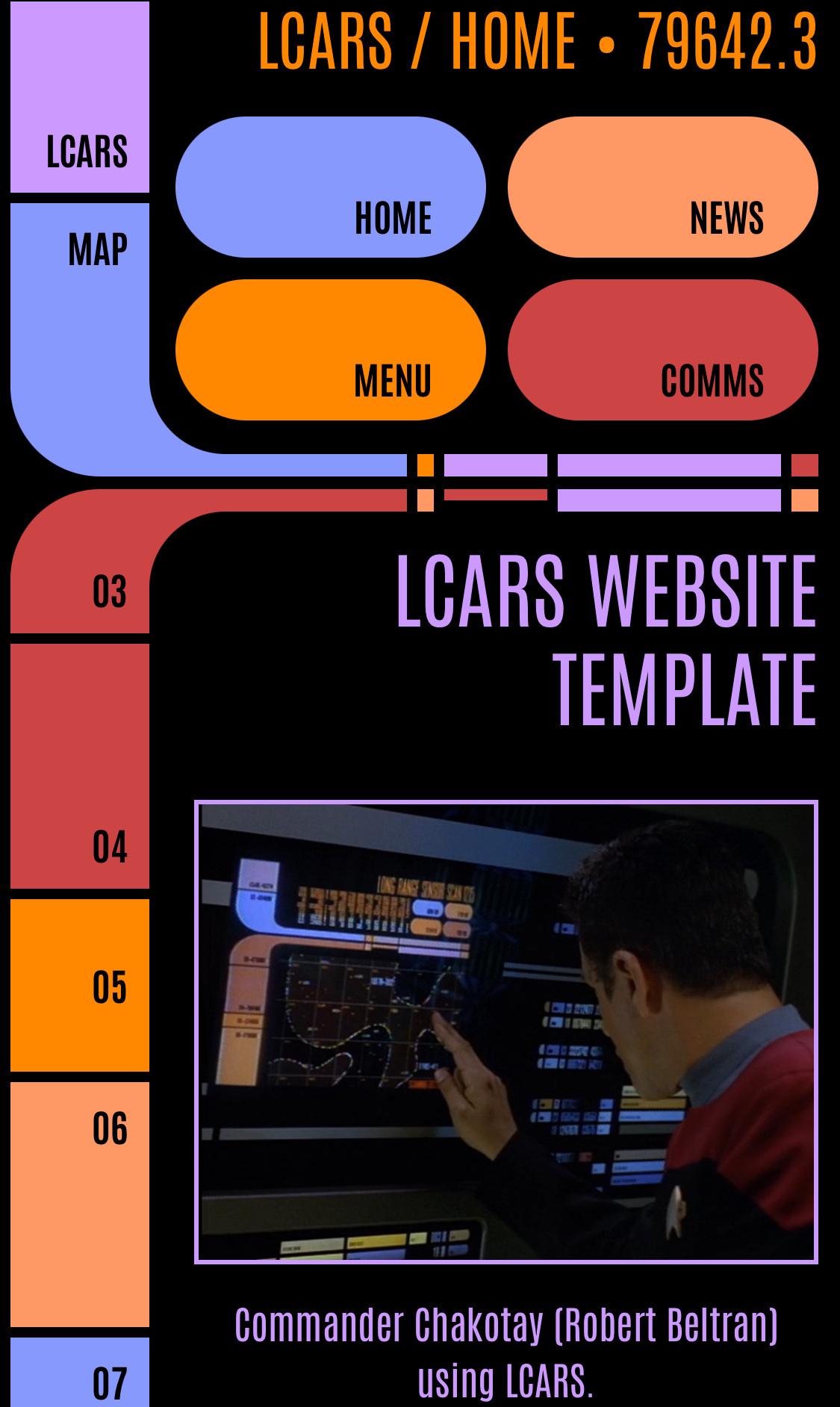

Someone (not me) needs to adapt this ST:NG LECARS layout for Micro.Blog

Palms and steel.

Vertical City, Falling Sky

Angles.

I began reading Alan Moore’s Jerusalem this time last year. The book clocks in at a hefty 1,266 pages, and while it’s never been a slog, it has been a slow-going read until I found myself in the current chapter, which is all in Finnegan’s Wake Joyce-speak. My reading has dropped to a crawl, and the experience alternates between confounding and delightful, sometimes both simultaneously. Consequently, I’m having trouble following the chapter’s plot because my brain is working overtime to parse what I’m reading. And as an unanticipated side effect, my brain is still in Joyce mode when I read standard prose, making reading all the more magical.

📺 Millennium, S 2 E 03 “Sense and Antisense” (1997)

This episode was steeped in conspiracy theories and seemed more like something out of The X-Files. It was clear by the third of the way through that this episode wouldn’t have a conclusion; instead, it was more about advancing the season’s story arc, making it an unsatisfying watch. On the other hand, it featured Clarence Williams III of The Mod Squad fame, which was pretty cool.

📺 Harsh Realm, S 01, E 02 Leviathan (1999)

The late 90s were when television programming fully adopted serial storytelling. Well, that’s not entirely true. Soap operas had been on air for the last few decades, but this was the first time it was applied to genre fiction on prime time, and I was ready for it. That said, this episode was a clunker, and I don’t think I would continue watching the series. On the plus side, Mark Rolston makes an appearance as a scumbag merc who is hard of hearing, which was a nice twist.

🍿 Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992)

Last night I watch Bram Stoker’s Dracula on the big screen, sharp as a coffin nail. Hadn’t seen it like that since ’92, back in Boston, when I hit the theater with the crew from Slaughter Shack. The frontman was tangled up with Sadie Frost—engaged, dating, whatever. I’ve seen the damn thing a half dozen times since, maybe more. Crowd was younger than I figured—bright-eyed, full of blood, and barely old enough to know what they were watching. A few phones flickered like rats in the walls, but they stayed quiet. Smart. Dracula don’t like distractions. And neither do I.

Slopping through the slough of a chapter now, ink-thick and babble-tongued in Alan Moore’s mad Jerusalem, I am. yes, dragfoot and fogbrained, sentence winding round itself like a drunken priest’s sermon, and poor old Jimmy J. himself, God rest his lexical gymnastics, would tilt his noble head and mutter what in the bally blue blazes is this babelish blather, aye, scratching at scalp in baffled awe.

The Vox Macabre podcast talked about this flick and it’s been on my radar ever since. Good to see Matthew Fox still in the game.