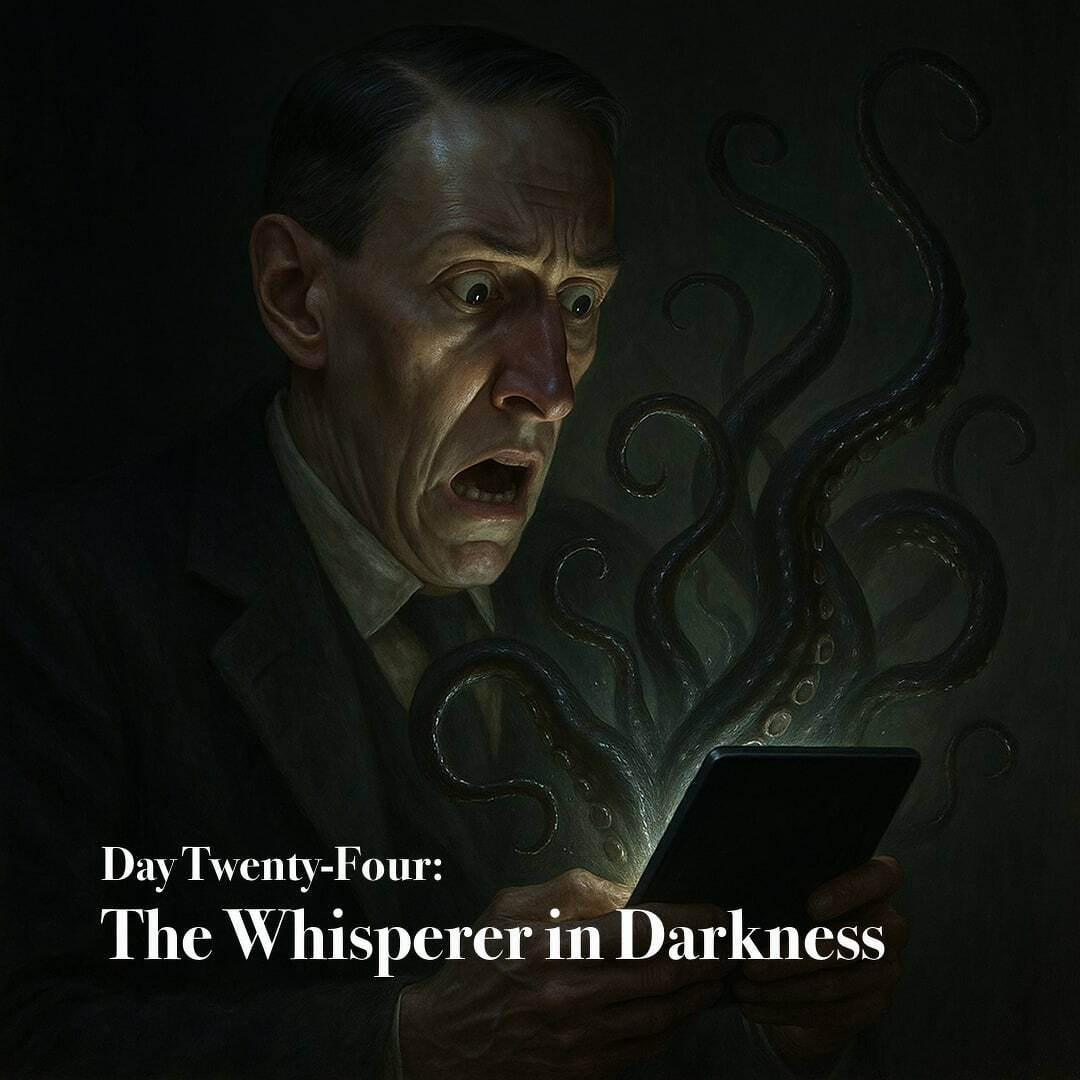

The Whisperer in Darkness

I had just concluded my reading of H. P. Lovecraft’s The Whisperer in Darkness before venturing into the nocturnal chill to attend a screening of Guillermo del Toro’s Frankenstein at the local arthouse theater. Del Toro’s creations never fail to lure me, for in his visions I sense a kinship with the same cosmic dread that haunted the Providence dreamer. Yet I cannot help but yearn for the day when he at last summons his long-desired adaptation of At the Mountains of Madness, that ultimate revelation of mankind’s insignificance beneath the polar wastes. Until that accursed miracle arrives, Hellboy must suffice, with its abominable Cthulhu-like hounds born of unearthly seas and the spectral conjuring of Rasputin amid the Himalayan frost.

And now, as the final echoes of the film dissolve into the night, I return to the tale that began this descent into wonder and horror: The Whisperer in Darkness, whose whisper still threads the wind beyond the stars.

Albert N. Wilmarth, instructor of literature at the ancient and brooding Miskatonic University, found himself drawn into a web of unholy revelations when word spread of uncanny shapes glimpsed amid the swollen rivers of Vermont. At first he mocked such rustic legends, attributing them to the fancies of backwoods minds. Yet the arrival of letters from one Henry Wentworth Akeley, a hermit dwelling in the shadowed hills near Townshend, began to erode his reasoned disbelief. Akeley wrote of voices in the night, of monstrous presences that crept from the forest, and of rituals whispered in the names of Cthulhu and the crawling Nyarlathotep.

Each message grew more dreadful than the last. Akeley spoke of the slaughter of his hounds, of nocturnal gunfire, and of grotesque forms that bled a sickly green fluid unfit for any earthly vein. Then, without warning, the tone altered. The terror gave way to awe. Akeley declared that the beings were not hostile but divine, their knowledge a gateway to the boundless gulfs of infinity. He begged Wilmarth to come at once, promising revelation beyond mortal ken.

When Wilmarth arrived, he found Akeley wasted and still, seated in shadow, his voice a strange, droning murmur that set the nerves on edge. The frail host spoke of cosmic voyages, of minds released from flesh and sealed within metal cylinders to traverse the black gulfs between worlds, bound for Yuggoth, the outer sphere men call Pluto. One of these imprisoned minds spoke to Wilmarth, extolling the glory of such a fate.

That night, haunted by whispers that no human throat could form, Wilmarth crept forth and made a discovery too hideous for sanity. The thing in the chair was gone, leaving only the robe and within it those ghastly remnants that mocked the shape of man. Fleeing in madness, he left the accursed place behind. When daylight came, the farmhouse was found desolate, the traces of battle erased. Only Wilmarth knew the unspeakable truth: that what had worn Akeley’s countenance was not a man at all, and that the true Akeley’s brain had already been borne away into the cold abyss.

In “The Whisperer in Darkness,” there stirs a shadowed homage to Arthur Machen’s The Novel of the Black Seal, for in its haunted pages Lovecraft walks once more the accursed hills where elder beings are said to brood beneath the soil of mankind’s ignorance. Scholar Robert M. Price has discerned in it not mere influence but transformation, a reawakening of Machen’s dreadful vision. As in that earlier chronicle, a seeker of forbidden lore ventures into the lonely uplands, drawn by relics of a prehuman race whose traces yet stain the stones of the Earth.

Lovecraft, ever the dissector of myth, divides Machen’s doomed Professor Gregg into two forms: Wilmarth, the hesitant chronicler of unspeakable truths, and Akeley, the scholar whose faith in reason dissolves before the inhuman reality that calls to him from the hills. Both tales murmur of grotesque shapes glimpsed beside the river’s flow, of those who vanish from the world to serve unseen masters.

Echoes of Robert W. Chambers and Ambrose Bierce drift through Lovecraft’s prose, their spectral dread woven into his tapestry of cosmic horror. Even the tale’s beginning, with its deluge upon the Vermont countryside, rises from earthly record, while the monstrous notion of brains encased in eternal machinery betrays a whisper from J. D. Bernal’s The World, the Flesh, and the Devil, a modern scripture of unholy possibility. Thus the story becomes a convergence of visions, a hymn to the old terrors reborn in the age of reason.