The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath

Yesterday, as I perused “The Strange High House in the Mist” from that blasphemously vast tome, The Complete Works of H. P. Lovecraft, I pondered with dread how I might reach its end ere the waning of the month. By my reckoning, the final tale would fall upon the eve of All Hallows, yet the accursed volume mocked me, revealing but a third of its depths explored.

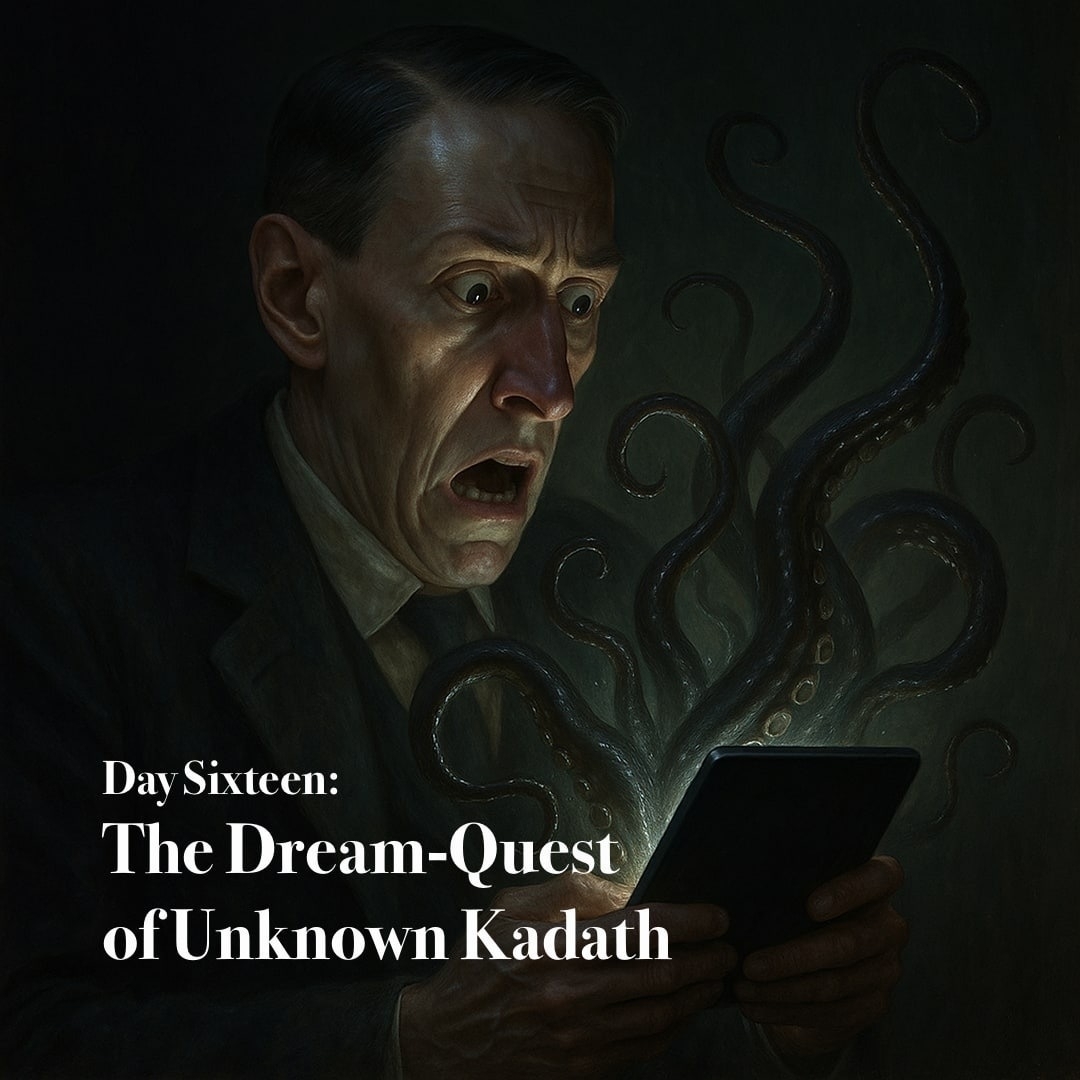

Today, in venturing through H. P. Lovecraft’s “The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath”, the riddle found its answer. For that tale is no mere story but a delirious odyssey, a fevered scripture of dream and revelation. Four mortal hours slipped by like whispers from the abyss, and when at last I closed the book, I was unsure whether I had read it, or dreamt it. The memories that lingered were but phantasmal fragments: shimmering towers, impossible skies, and gods that moved like shadows beyond the waking mind, as if illustrated by the likes of Winsor McCay and P. Craig Russel. It seemed as though the tale had read me, drawing my soul across the veiled gulf between sleep and madness.

In the half-lit gulfs where sleep and waking intermingle, Randolph Carter beheld oft a city of opalescent glory—its towers radiant, its streets suffused with the beauty of forgotten suns. Yet when that dream-vision fled from his nightly wanderings, Carter, undaunted, swore to ascend unto dread Kadath, where the gods of dream brood in their cold and perilous silence. Priests in border temples muttered of doom, whispering that the gods themselves had veiled the city from his sight. Still Carter pressed on, threading the perilous lore of Zoogs, heeding the counsel of Atal in fur-haunted Ulthar, and seeking the visage of gods carved colossal on mountain slopes.

His wanderings grew dire. Seized by turbaned slavers, he was borne to the moon and thrust before the obscene moon-beasts, servants of Nyarlathotep. Yet the cats of Ulthar, his steadfast allies, swept down in yowling hosts to bear him free. Nightgaunts, faceless and winged, dragged him into the abyssal underworld, but ghouls led by his comrade Richard Pickman, now forever changed, guided him through the loathsome city of the Gugs. Thence he strode to Celephaïs, where King Kuranes, who had forsaken life for dream, sought vainly to dissuade him. Onward he pressed to Inganok, to Leng, and to the accursed monastery whose priest none dare name, where Carter glimpsed a truth that froze his soul.

From moon-beast citadels to nightgaunt wings, he battled, bargained, and climbed until at last he stood in Kadath itself. Yet the halls were empty, abandoned by the gods who had fled to dwell in Carter’s own lost childhood Boston. There, in regal mockery, Nyarlathotep revealed the truth and sent Carter spiraling not to his sunset city but unto the blind idiot Azathoth at chaos’ center. Only the sudden remembrance of dream’s dominion wrenched him awake, sparing his soul. Nyarlathotep, balked, seethed amidst Kadath’s black spires, while the mild gods crept back to their stolen city.

“The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath,” wrought of strange borrowings, from William Thomas Beckford’s Vathek, from Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Barsoom, from L. Frank Baum’s Oz, and from Lord Dunsany’s jeweled phantasies, stands both reviled and revered. Some find it unreadable, others hail it as akin to Lewis Carroll or George MacDonald. Lovecraft himself dismissed it as “poor practice,” yet even Dunsany, shown its pages, confessed with ironic grace: “I see Lovecraft borrowed my style.”