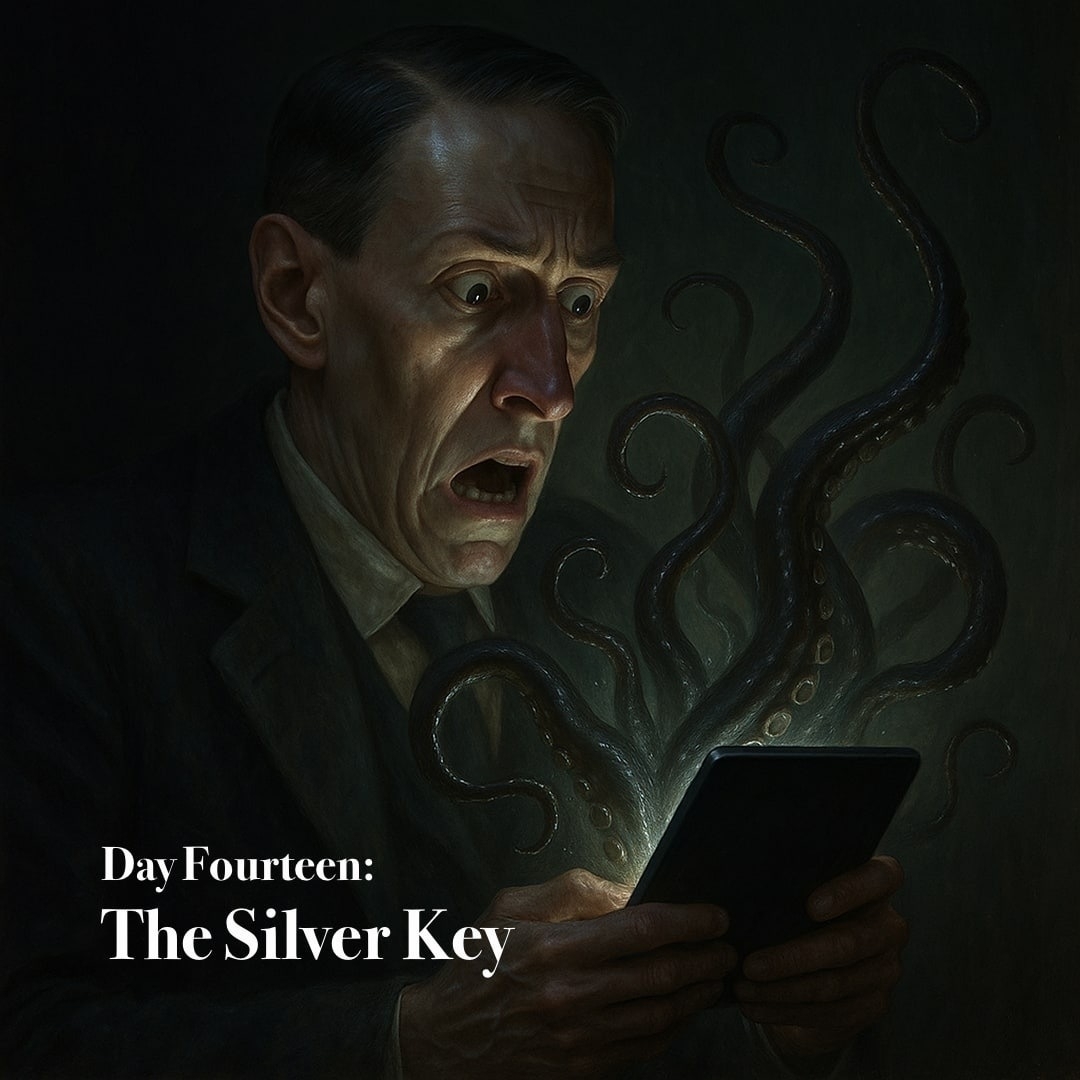

The Silver Key

As you might well surmise, the quiet custom of reading one tale each October day from the accursed pen of Howard Phillips Lovecraft provides a curious occasion for reflection upon my long and changing acquaintance with his work. When first I was introduced to his singular literature, I had not yet reached my eighteenth year, and now I find myself well into the somber corridors of middle age. Time has altered not only my countenance but also the quality of my admiration, so that what once thrilled me now leaves me pensive, and what once seemed lesser has grown in secret power.

In revisiting the tales of the recluse of Providence, I have come to favor his stories of the supernatural above those of his vast and dreadful cosmos. The subtle horrors, rooted in the mortal and the spectral, touch my spirit more deeply than those that whisper from beyond the stars. I take especial delight in again meeting the shades of tales I have long cherished, such as “In the Vault” and “Pickman’s Model”., which remain as potent and as grave as when I first encountered them. None have diminished in my esteem, and others, such as “The Silver Key”, now reveal depths I once overlooked.

In the impatience of youth, I would hurry through “The Silver Key”, eager to reach what I believed were the greater marvels of Lovecraft’s mythic imaginings. Yet now, with the weariness and reflection that come to men of my years, I find myself drawn to its quiet melancholy and to its dreamer, Randolph Carter. He too lamented the passing of mystery from the world, and I, like him, perceive that we dwell in an age stripped of its wonder. The iron spirit of pragmatism has banished enchantment from our waking lives, leaving us poorer, though we are too proud to confess it.

Not always do I feel this melancholy, yet there are moments when I look upon the world and sense that it has grown barren of the unseen. In such hours, I cannot help but wish that I, too, possessed Carter’s key, that fragile token which opens the hidden door between dream and remembrance, and leads once more to the lost kingdoms of the soul.

At the age of thirty, Randolph Carter beheld with despair that he had lost the key to that mystic portal which opens upon the gate of dreams. No longer could he summon the ineffable splendors of enchanted cities and unearthly beings, for the grey weight of waking science and the barren creed of the commonplace had dulled his once-radiant vision. In vain he sought meaning among the schools of philosophy, but their sterile systems brought him naught save emptiness, until at last he fled into solitude.

Then, in the dim recesses of sleep, his long-dead grandsire whispered of a hidden relic—an ancient silver key wrought with cryptic arabesques—resting in the attic’s dust. Carter seized it and returned to the cavern of his boyhood, where, upon uttering the syllables of his blood, he slipped from mortal time and was reborn as a child of ten. Strange it was that kinfolk recalled how, from that tender age, he spoke with uncanny foresight of futures yet unshaped.

The chronicle closes with a haunting promise: that Carter now reigns in a dream-city beyond mortal sight, sovereign of realms where the silver key unlocks the ultimate mysteries of the cosmos.

Thus “The Silver Key” joins his other chronicles: “The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath,” “The Statement of Randolph Carter,” “The Unnamable,” and at last “Through the Gates of the Silver Key.” Its tale of spiritual groping recalls J.K. Huysmans’ À rebours. Scorned by Weird Tales in 1927, then grudgingly printed a year hence, it was greeted by readers with “violent distaste,” though its eldritch music endures for those attuned to the hidden harmonies of dream.