Pickman’s Model

I have ever cherished H. P. Lovecraft’s sinister chronicle “Pickman’s Model”, not solely for the grim savor of its narrative, but because it entwined itself with a pastime of mine in years long past. In a session of The Call of Cthulhu, that dark game of dread imagination, I assumed the guise of Robert Pickman, brother to the accursed artist Richard. My Robert was a man of wealth and standing, who spoke but sparingly of his birth. He met his end beneath the knives of cultists, a glorious death steeped in the ichor of forbidden rites. Only later did I learn that our Keeper of Arcane Lore, lord of the tale and master of the dice, had never perused “Pickman’s Model,” nor many of the other eldritch writings of Lovecraft himself. The revelation astonished me, yet the game was no less delightful, even if my homage to that dire tale was lost in the shadows.

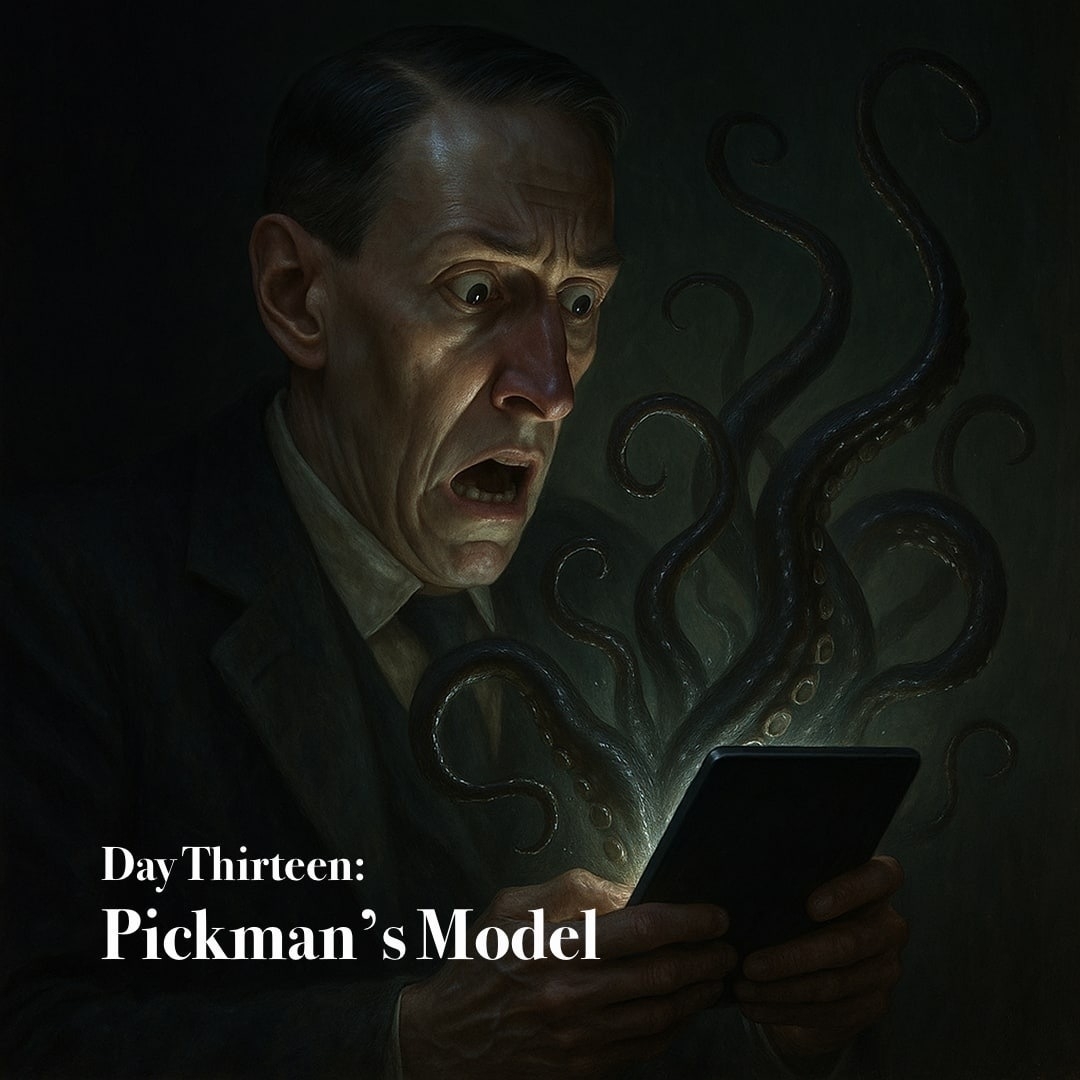

Richard Upton Pickman, the Boston painter, wrought canvases so grotesque in their verisimilitude that the art-world cast him out as a leper. A confidant tells of visiting his hidden gallery in a noisome slum, where images grew more foul and unearthly until the final vast canvas revealed a red-eyed, canine horror rending human flesh. Shots rang out, and Pickman returned with a tale of rats dispatched, yet in his companion’s pocket lay a photograph, grim evidence that Pickman’s monstrosities were no dreams, but dreadful realities.

And yet Lovecraft did not leave him thus. In “The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath,” Pickman returns, now a ghoul, guiding Randolph Carter through nightmare realms. Scholar Robert M. Price observes that this ghoul-Pickman bears scant resemblance to the mortal artist, likening him instead to Tars Tarkas of Edgar Rice Burroughs’s A Princess of Mars. In technique, too, the tale is peculiar, for Lovecraft employed layered monologues and a colloquial tone seldom found in his work, a departure from the customary chill of cosmic indifference.