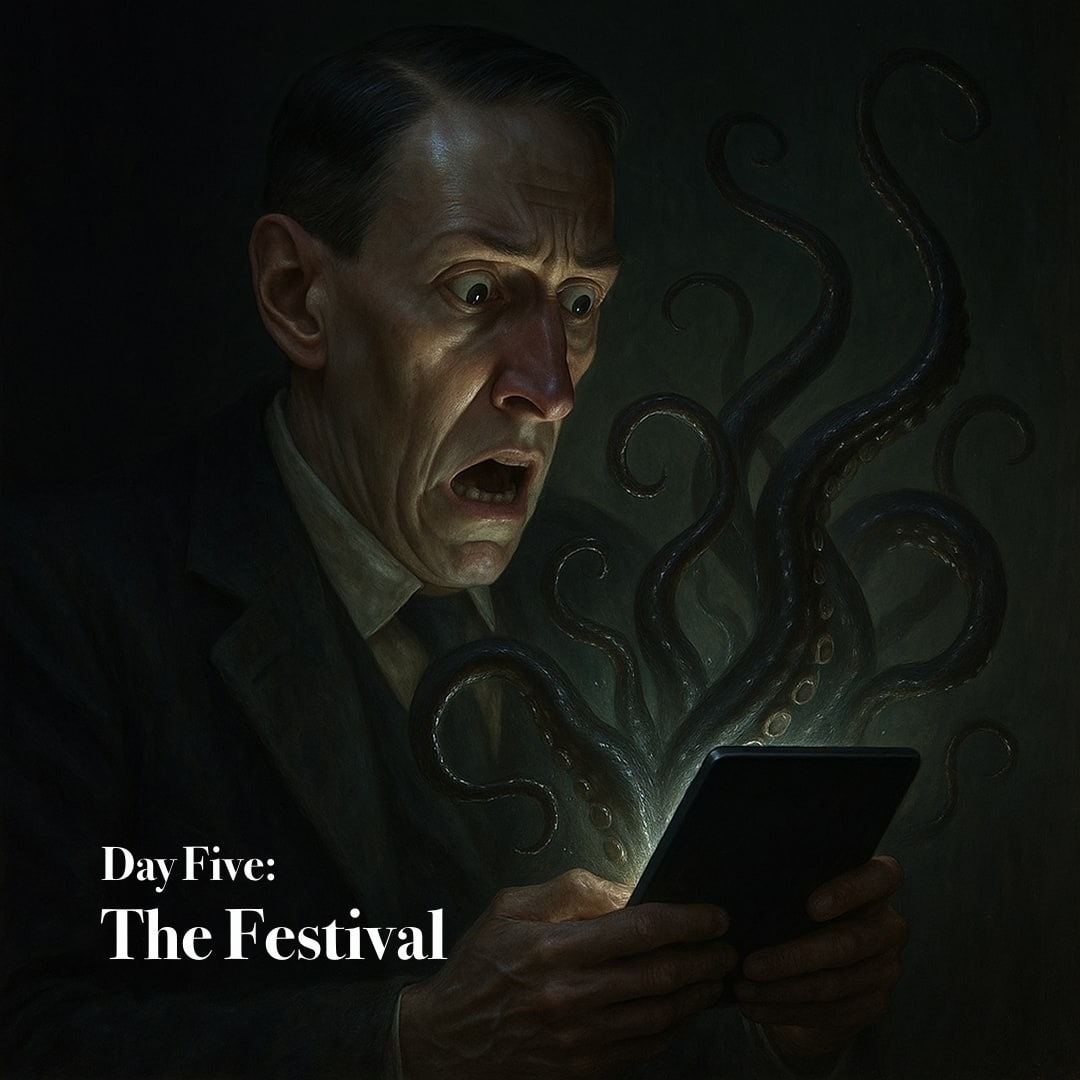

The Festival

As I set forth this day to attend my grandson’s Little League game, I prepare to join the throng of parents and kin who cheer the young players with cries of “Swing batter, batter,” while consuming hot dogs laden with mustard and relish. Yet, unlike my companions in this innocent ritual, I know that beneath the benign autumn sun, my skin will creep with remembrance of Lovecraft’s tale, “The Festival.”

In that dread story, an unnamed traveler comes at Yuletide to Kingsport, the ancient seaport of his forebears. He beholds crooked alleys, sagging houses, and the church that looms untouched by centuries. A mute elder, gloved and bland of countenance, guides him through ancestral halls where the Necronomicon lies among worm-eaten tomes. At the appointed hour, he joins a silent multitude of cowled figures, descending beneath the church to a subterranean shore where green flames belch and an amorphous flutist pipes to the abyss. There, winged horrors—neither beast nor man—bear the worshipers into gulfs unguessed. The traveler recoils, for his guide reveals proof of kinship and a face not human. In terror, he flings himself into the oily waters.

He awakens in a hospital, told he had walked from a cliff into the sea. Yet when he later reads in Arkham the blasphemous words of the Necronomicon, he finds them echoing all he has seen, speaking of corruption that spawns monstrous life and of things that walk when they were made to crawl.

Critics have marked the tale’s import. Lin Carter names it the first of Lovecraft’s works to root itself in witch-haunted Kingsport and the earliest to yield a lengthy citation from the dread Necronomicon. S. T. Joshi recalls that “The Unnamable” first introduced Arkham. Yet, he concedes that “The Festival” binds itself more deeply to the Mythos.