Celephaïs

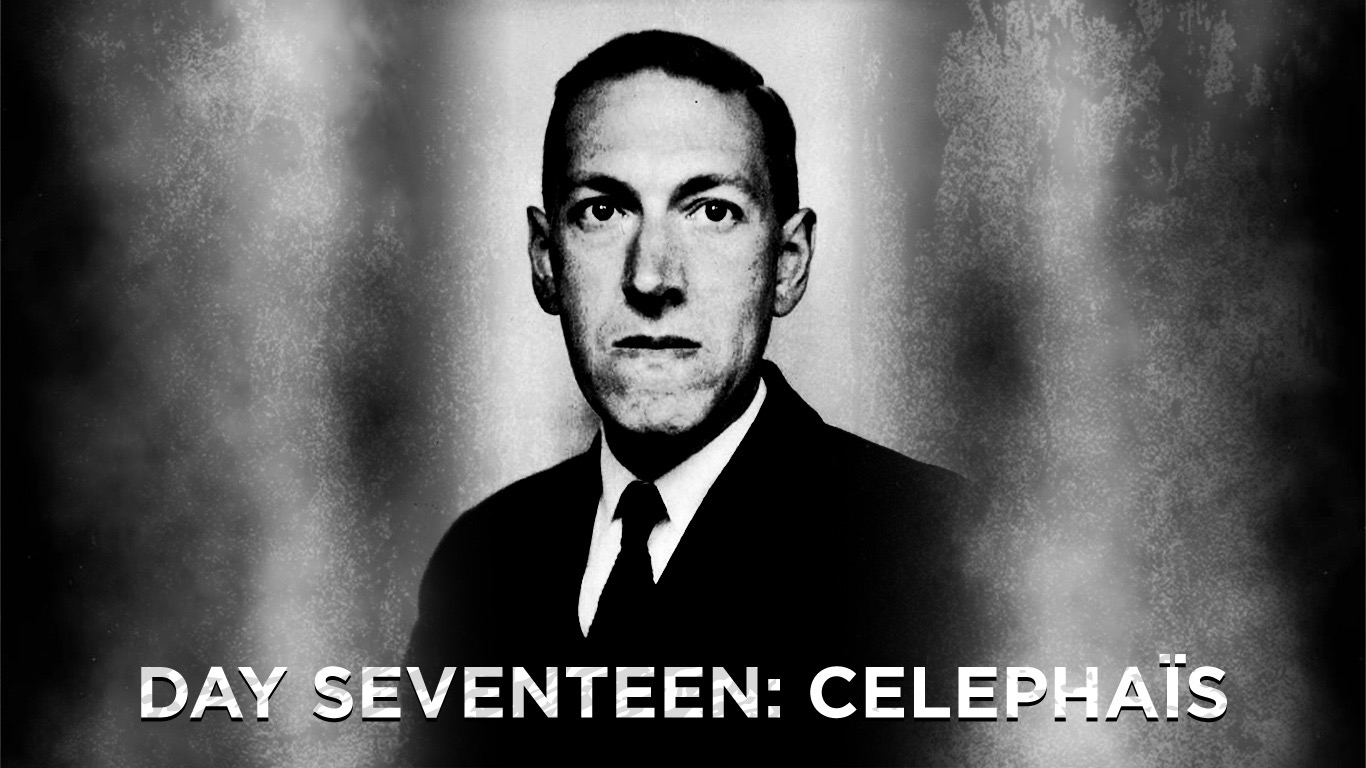

In this, the month of October, when the thin veil between the known and the unknown seems perilously frayed, I have returned to my venerable ritual: the daily immersion into the eldritch realms conjured by that grim architect of cosmic dread, H.P. Lovecraft. Yet as I tread these spectral paths, I have found myself ensnared by certain tales, disquieting not for their horrors beyond comprehension, but for the festering bigotry that, like a stench, clings to the pages of some of his works. These tales, repugnant in their smallness of spirit, mar the grandeur of his broader mythos.

Thus it was with a rare sense of reprieve that I turned to today’s reading—“Celephaïs”—a tale unlike the others, born not of the crude prejudices of men but from the deeper, purer wellspring of dreams. I find myself drawn to this story, not only for its ethereal beauty but for its origin, nestled as it was in Lovecraft’s own commonplace book, a fragment of a dream that his mind, so often clouded with darker thoughts, shaped into a vision of fantastical splendor. Like Lovecraft, I too have transmuted the ephemeral substance of my dreams into stories, and I hold in high regard all those who dare to do the same, who pluck the strange and ineffable from the vast night of slumber and bring it forth into the waking world.

For many months after that Kuranes sought the marvellous city of Celephaïs and its sky-bound galleys in vain; and though his dreams carried him to many gorgeous and unheard-of places, no one whom he met could tell him how to find Ooth-Nargai, beyond the Tanarian Hills.

In the twilight hours, as the mists of an eldritch London coiled about the crumbling tenements, Kuranes—though this name be but a whisper in the nocturnal realm, his true name lost to the aeons—wandered, a forlorn relic of the once-proud English gentry. His youth, adorned with the trappings of privilege and the intoxicating beauty of pastoral estates, had long since decayed into the dust of forgotten epochs. Yet in the spectral depths of his dreams, stirred by nameless forces, he once more glimpsed that which mortal eyes had scarcely dared to perceive: Celephaïs, a city born not of stone and labor but of the intangible substance of dreams.

In his fortieth year, estranged from time and fortune, Kuranes found solace only in slumber, where the luminous spires of Celephaïs, long faded from his youthful visions, shimmered anew on the horizon of his mind. And so, in thrall to the dream-world, he relinquished his grasp upon the waking realm, slipping ever deeper into the shadowed recesses of the unknown. The mundane became a distant memory as knights, clad in the raiment of forgotten ages, emerged from the mists, guiding him across a landscape that seemed at once familiar and alien—medieval England, with its ancient castles and winding, time-worn paths, echoing with forgotten tales.

At last, they came upon the ancestral estate of his boyhood, the manor where his laughter had once danced upon the winds of a summer long past. But beyond, further still, lay Celephaïs, the city of his deepest yearning. There, Kuranes ascended to the pinnacle of his forgotten majesty, reigning not only as monarch but as a deity among dreamers, his every thought shaping the contours of that enchanted realm.

Yet in the cold, unforgiving reality from which he had fled, his body was found—pale, lifeless—carried by the inexorable tides to the tower that had once stood as a sentinel of his lineage. Now it was claimed by a parvenu, an unworthy usurper of a name that history had all but erased, while Kuranes himself had transcended both time and death, a king eternal in the city that dreams had made.