The Tree

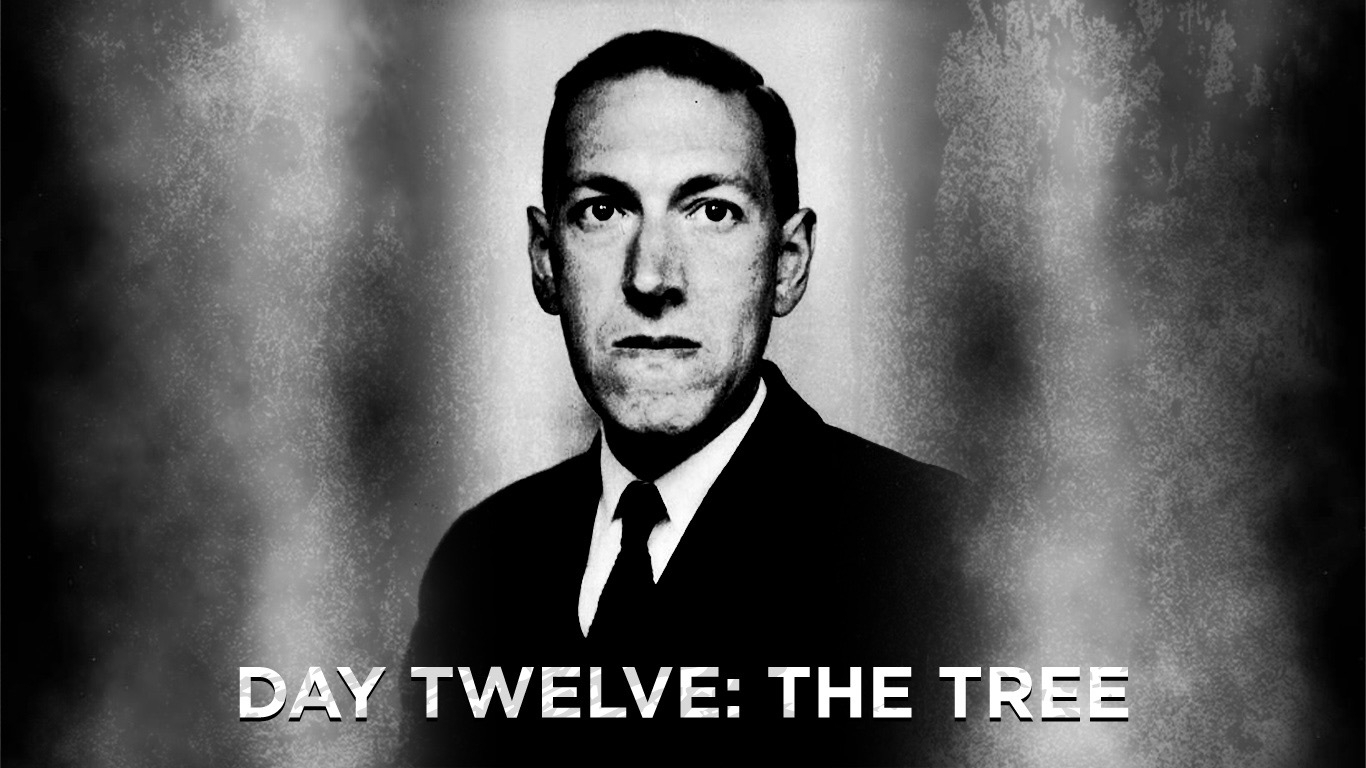

Though I find myself gratified by the renewal of my long-cherished tradition—reading, each day throughout October, a tale spun by that master of cosmic terror, H.P. Lovecraft—I confess an unshakable disquiet. There is something faintly profane in absorbing these eldritch horrors through the cold, pallid luminescence of a backlit Kindle screen rather than from the ancient, worn pages of a proper tome. Yet, what choice have I? The modern world, in all its indifferent progress, has forced my hand. And so be it.

But the olive grove still stands, as does the tree growing out of the tomb of Kalos, and the old bee-keeper told me that sometimes the boughs whisper to one another in the night-wind, saying over and over again, “Οἶδα! Οἶδα!—I know! I know!”

Today’s story, “The Tree,” is one I have read before—yet now, with the deeper knowledge gleaned from perusing the works of Algernon Blackwood and Arthur Machen, I find myself newly attuned to Lovecraft’s craft. His tale grows more haunting with each re-reading, as though the fabric of its mystery darkens with age.

In the desolate foothills of Mount Maenalus in Arcadia, an olive grove casts a sepulchral pall over a crumbling villa and an ancient tomb of marble. From this ground, there rises a grotesque, distorted tree—a hideous mockery of human form, its gnarled roots shifting the very stones of the tomb beneath it.

The tale, as our narrator relays it, came from the lips of a simple beekeeper. In those ancient days, the villa was home to two illustrious sculptors, Kalos and Musides. Though bound by the deepest of friendships, they differed greatly in their souls. Kalos sought the quietude of the olive grove, where he communed with strange inspirations; Musides reveled in the life of the city. The Tyrant of Syracuse sent emissaries to these two, demanding a statue of Tyché, goddess of fortune. Yet, as fate would have it, Kalos fell gravely ill, leaving Musides to watch in despair as his friend grew weaker.

As Kalos lay dying, his calm stood in stark contrast to Musides’ grief. He made one strange request—that olive twigs be buried near his head when his inevitable death came. And so it was. From that burial sprouted a great olive tree, unnaturally swift in its growth, overshadowing the unfinished work of Musides.

Three years passed, and Musides completed his statue. Yet in the end, a malevolent storm, like the very hand of fate, came howling down from the mountain. The next morning, the villa was found in ruins, the statue crushed beneath the twisted boughs of the tree, and Musides vanished without a trace.

Thus, the story ends as it began—with that grim reminder: “Fata viam invenient”—fate will find a way, no matter how we struggle against its inescapable pull.