Fasting one day a week for the next month to see how it goes. Today has been going well, only a touch peckish. Looking forward to a bowl of ramen this evening. 🍜

Fasting one day a week for the next month to see how it goes. Today has been going well, only a touch peckish. Looking forward to a bowl of ramen this evening. 🍜

Finished reading: Oklahoma City by Andrew Gumbel 📚

Bravo.

Bummed that Las Cuatro Milpas and Buona Forchetta have closed. Fond memories of both places.

Let the Yuletide ring with my Winter Wonderland mix. Enjoy!

Finished reading: On the Suffering of the World by Arthur Schopenhauer 📚

Read this in a Recommendo newsletter:

I’m one of those people who loves to look up the menu before arriving at a restaurant, but I often get confused by menus full of complex food jargon. Now, I use AI to translate them for me. My go-to prompt: “Translate this menu into simple, everyday language and describe the taste and flavors of each dish.” This has even helped me become more adventurous and order dishes I’d normally avoid.

The tradition of Thanksgiving fireworks in my neighborhood continues.

Finished reading: A Brief History of Seventh-Day Adventists by George R. Knight 📚

When I was a kid, Friday nights were something special. My dad and I had our little ritual: we’d head down to the neighborhood pizza shop for a pie or some subs, then stroll across the street to the corner store to grab a bottle of soda and a comic book. That was our routine, and, truth be told, that’s how I learned to read.

After dinner, I’d curl up beside my dad while he read aloud the latest adventures of Superman or Batman. The next day, I’d gather my friends and “read” them the same story. Really, I was just repeating what I remembered and filling in the blanks with the pictures, but that was enough to light the spark. Week after week, comic after comic, my imagination and my vocabulary just kept growing.

As I got a little older, I graduated from superheroes to something darker. Down at the pharmacy, I discovered Creepy, a black-and-white horror anthology full of monsters, madmen, and buxom women. Those stories were wild! Gruesome, spooky, and just a bit naughty. I loved every page.

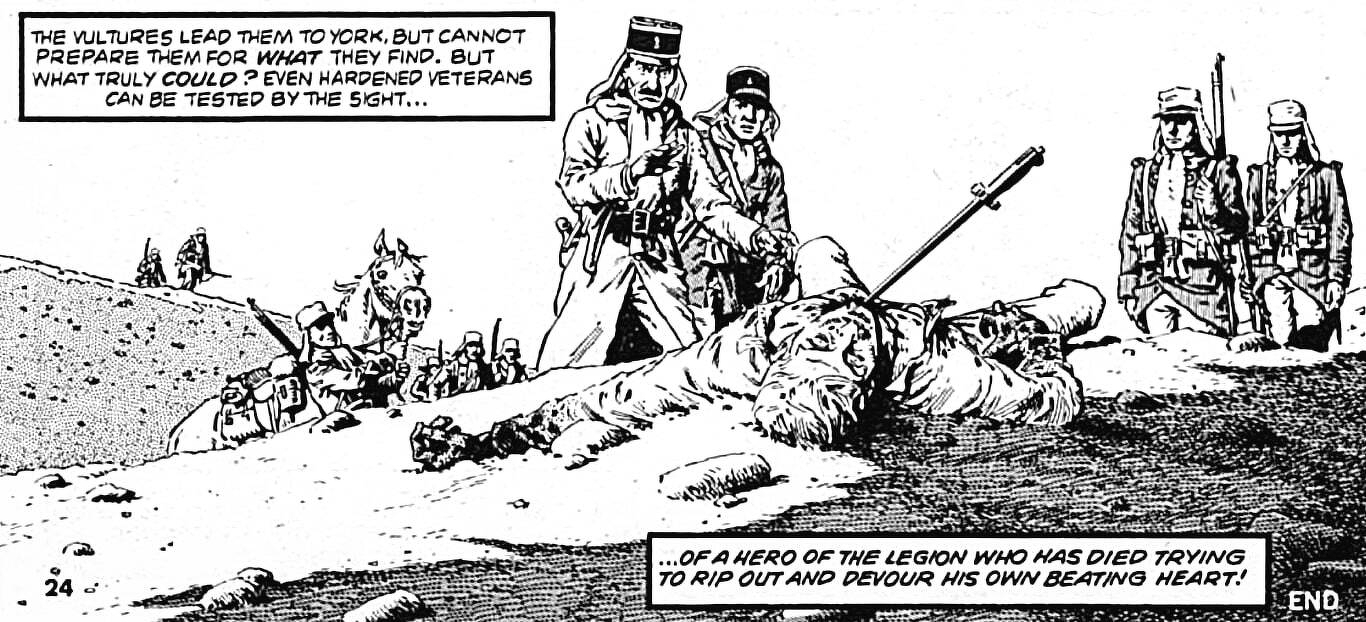

One issue in particular got its claws into me: Creepy #112. Inside was a story called “Warrior’s Ritual,” written by Archie Goodwin and illustrated by John Severin. It told of a Legionnaire who drew his strength from devouring human hearts. Sounds awful, I know, but to my pre-teen brain, it was unforgettable.

Earlier this week, feeling nostalgic, I tracked down that very issue on eBay. “Warrior’s Ritual” still hits just as hard all these years later. In fact, I think I appreciate the craftsmanship even more now. Goodwin’s sharp storytelling, Severin’s rich linework are stellar. And the rest of the issue? Just as strong. There’s “Homecoming,” beautifully drawn by Al Williamson, about a man searching through dimensions for a new world after Earth’s ruin; “Nobody’s Kid,” a gut-punch of a story about child abuse; “Relic,” my first taste of Walt Simonson’s art, about creatures living on a different timescale than ours; “Beastslayer,” a haunting hunter’s tale drawn by Val Lakey; “Sunday Dinner,” written by Larry Hama and illustrated by Auraleón, serving up a cannibal’s twist; and finally, “The Last Sorcerer,” where Alex Niño turns Archie Goodwin’s script into something that feels like pure magic, with page layouts, negative space, and every panel alive with energy. I loved it so much that I sent Alex an email thanking him bringing this yarn to life. The cover by Richard Corben seals the deal: a vampire, his victim, and pure gothic glory.

All that for two bucks back in 1979, and ten dollars today on eBay. Still a bargain for something that shaped my imagination.

My grandson told me he’s getting me a “scary comic book” for Christmas, which of course means his parents are buying it. I told them to swing by a comic shop and pick up Creepy #115, another one that’s dear to my heart, and maybe just a little dark for the soul.

Ever since I first heard about the InkPalm Plus, I’ve been a little bit obsessed with these phone-sized eReaders. There are more of them out there than I expected. Off the top of my head, I can name the BOOX Palma, the Viwoods AiPaper Reader, and the Xteink.

I picked up the InkPalm Plus myself, and to be honest, I’m not all that thrilled with it. Right out of the box, the system is geared toward Chinese readers, and it took a bit of tinkering to switch everything over to English. I can read the books I’ve bought from Rakuten just fine, but the device does not support Amazon Getting my DRM-free books on there is such a chore that I’ve pretty much given up. The biggest letdown for me, though, is that I can’t highlight or take notes. That might not matter to everyone, but since I do a lot of research, it’s a dealbreaker. Still, for something I picked up for under a hundred bucks, I really can’t gripe too much.

Having this little InkPalm has made me realize what I actually want from a pocket-sized reader. I want to open any eBook I’ve bought from Amazon or Rakuten, access my DRM-free library without jumping through hoops, and highlight and make notes as I go. And I don’t want to spend more than $150 to do it. That rules out the BOOX Palma and the Viwoods AiPaper Reader since they’re both over $200. The Xteink is also out because it only supports non-DRM books, and those buttons on the front drive me crazy.

The funny thing is, as much as I’m fascinated by these tiny readers, I probably wouldn’t use one all that much. When I have a choice, I’ll always grab my Kindle Paperwhite or Kobo Clara Colour. I’ve noticed that my reading comprehension just nosedives when I’m trying to read something long on a screen the size of a phone. So why do I still want one of these little eReaders?

Don’t mix your shit with their bullshit. —Guy standing next to me

Finished reading: Paleomythic by Graham Rose 📚

📺 Harsh Realm, S 01, E 03 Inga Fossa (1999)

In the 90s, television was still learning how to adapt primetime series into episodic series. The awkwardness shows in series like Harsh Realm. It baffles me because soap operas have been doing this sort of thing for decades. That said, despite the clumsiness, there were some moments I enjoyed in this episode, like White Zombie appearing in the soundtrack. I also got a kick out of the luchadore wrestlers that were clearly inspired by Mortal Kombat. But other than that, this episode was something of a snooze.

📺 Millennium, S 2 E 04 “Monster” (1997)

Three months have passed since I last returned to Millennium. It felt necessary. I had grown used to the polish of modern television, the kind of storytelling that leaves no rough edges. Shows like True Detective set a bar so high that even Millennium, with all its haunted brilliance, feels like an artifact from a different age. It pushed against the limits of its time but could never fully escape them.

Kristen Cloke appeared in this episode. I remembered her from Space: Above and Beyond, unaware she had later starred in Final Destination and Black Christmas. She carries the same quiet intensity, the kind that belongs in Millennium’s world of terrible secrets.

Even the small details speak of another era, like Frank Black (Lance Henriksen) wearing his headphones wrong side up. Maybe he did not want to mess up his hair. When Frank smiles at a child, it feels like sunlight reaching into a cellar. In that instant, t is clear why Henriksen he is the soul of the show.

There is real fire here, too. Not the CGI bullshit we usually see in TV shows in movies these days. I was also delighted that the antagonist watch the gristly end of the original The Fly.

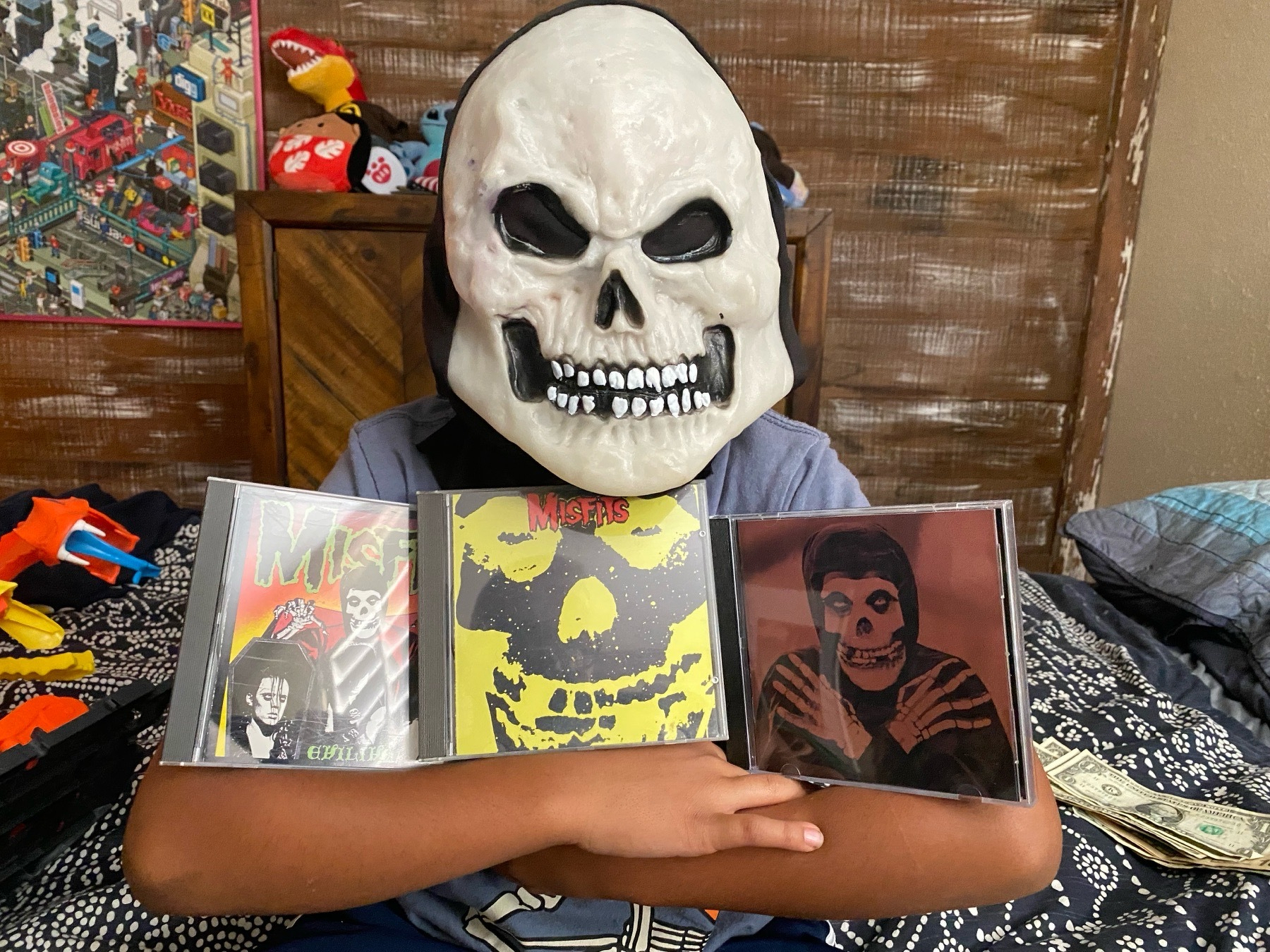

Misfit is a fan of The Misfits.

When I was yet a youth, in those dim hinterlands of memory where the shadows of bygone Octobers still coil and whisper, I first enacted the eldritch rite of reading one tale of Howard Phillips Lovecraft for each night of that haunted month. Long did that custom lie dormant, like some buried thing beneath alien stars, until last October when I dared again to unseal the tomb of that tradition.

In earlier years, I confined myself to the Del Rey volumes, those civilized and curated relics fit for mortal libraries. Yet some deep and spectral prompting compelled me, in the most recent season of falling leaves, to plunge into The Complete Works of H.P. Lovecraft, an abyssal ledger of tales both known and unguessed. I discovered, to my mingled dread and delight, that the corpus was vaster than mortal arithmetic had led me to believe, filled with nameless narratives lurking beyond familiar catalogues. A single October proved insufficient to exhaust them, and so I marked the remainder for the following year, as one might schedule the exhumation of long-interred bones.

Thus we arrive at the present hour, when the final offerings awaited me: The Shadow Out of Time—that chronicle of mind-shattering temporal exile—and “The Haunter of the Dark”, wherein the abyss itself peers back with light-devouring eyes. Two tales, aye, lest one be banished to the limbo of next October, and so I vowed to complete the cycle upon Halloween itself, an alignment too perfect to resist.

The day was not void of earthly burdens. I rose before dawn to confront The Shadow Out of Time, then surrendered myself to the banal servitude of labor at my infernal machine (the laptop, that modern grimoire of blinking sigils). From morning until gloaming I toiled, unbroken. Only when the last task was laid to rest did I consume “The Haunter of the Dark”, and with a strange, almost blasphemous satisfaction, I marked the final checkbox in OmniFocus, as if the sanity one loses in Lovecraft’s cosmos might be offset by tidy digital lists.

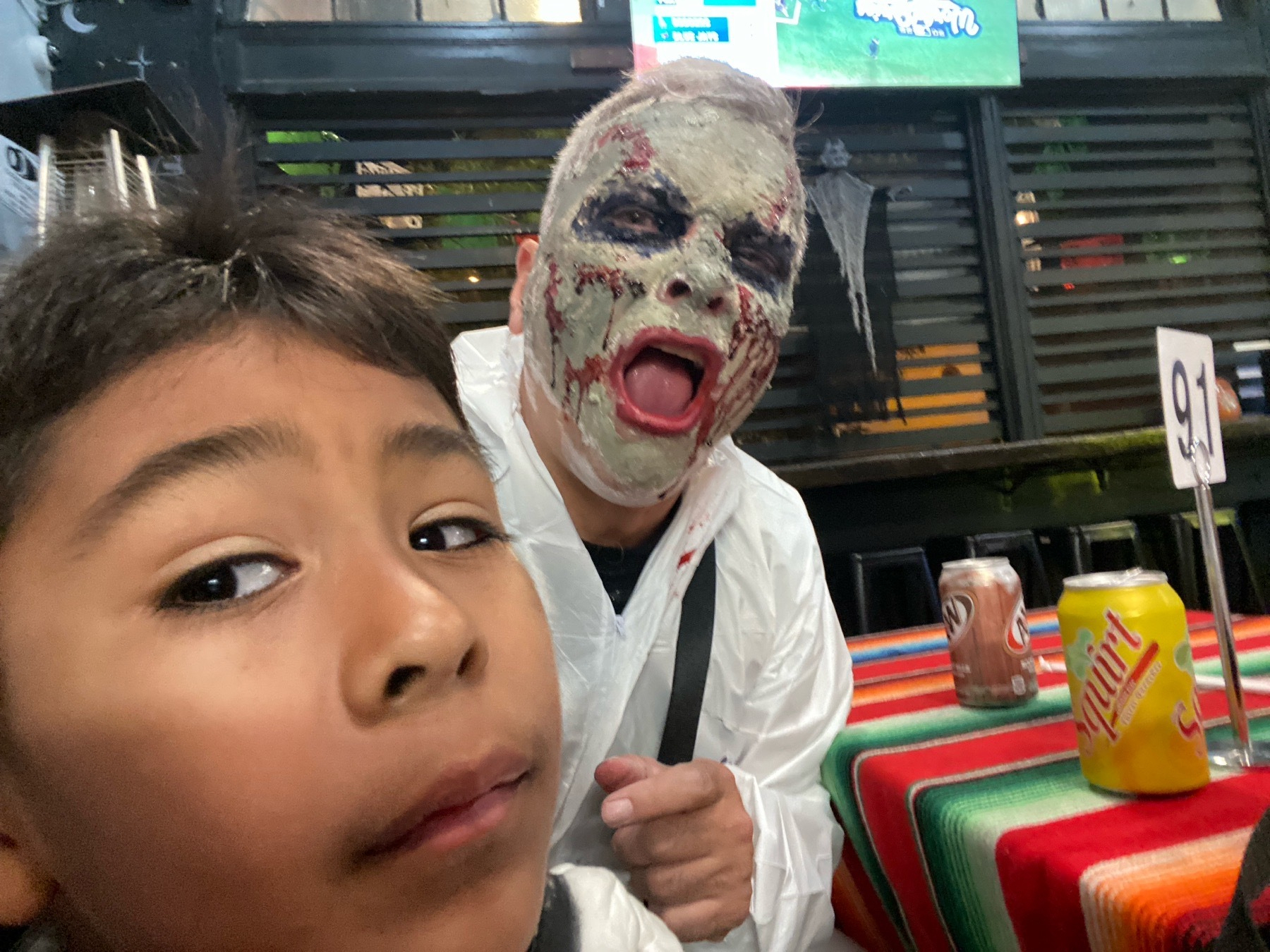

Yet even as I completed one ritual, another demanded my presence: the sacred family procession of Halloween night. With but forty-five mortal minutes at my disposal, I anointed my flesh with the gray and livid tones of the walking dead, that I might roam beside my grandson beneath the lamplight. The disguise succeeded too well; for in the aftermath, the unholy pigments clung to my skin like the residue of some corpse-dream, and even now my face bears a texture reminiscent of a schoolroom eraser, an object both innocent and ghostly, worn down by unseen pressures. I suspect it may take several days before the last trace of the grave relinquishes its hold.

So ends not only Halloween, but the full circuit of my Lovecraftian pilgrimage. Shall I resume this eldritch devotion next year? The angles of time are uncertain. Perhaps another author of cosmic anxiety, one Thomas Ligotti, shall whisper to me from the void. We shall see what shapes form in the darkness.

For now, dear reader, I thank you for accompanying me on this strange itinerary of ink, madness, and tradition. May your dreams be haunted, in the gentlest possible way.

The Shadow Out of Time

Professor Nathaniel Wingate Peaslee of Miskatonic University recounts a span of years steeped in mystery and dread, stretching from 1908 to 1935. On the morning of May 14, 1908, as he lectured upon the dry certainties of economics, an unseen force seized his mind, casting him into a coma from which he awoke a stranger to his own flesh. His words, gestures, and desires were no longer his own. Those who had loved him recoiled in fear, for they sensed a presence not of this world. Only his youngest son, Wingate, clung to the fragile hope that the father he knew might one day return.

For five years the alien intelligence that ruled his body wandered across the earth in pursuit of ancient knowledge and secret places forbidden to men. Then, in September of 1913, Peaslee’s rightful self reawakened, bewildered and haunted by dreams of impossible cities beneath strange suns. He sought to dismiss these visions as madness, yet the shadow of truth grew darker as he uncovered chronicles of others who had suffered the same fate across the ages.

His memories, once recovered, revealed that his mind had been seized by the Great Race of Yith, beings of vast intellect who lived two hundred million years in the past. They had mastered the frightful art of casting their consciousness across time, exchanging minds with creatures of other epochs to gather the sum of all knowledge. Within their mighty stone cities, the captive minds of alien hosts were treated with courtesy, allowed to study, to write, to wander the echoing libraries of their inhuman masters. When the Yithians’ purpose was fulfilled, the minds were returned, purged of memory, so that the delicate threads of time might remain unbroken. Yet their dominion had not endured, for the Great Race fell to the ravening “flying polyps,” and their brightest intellects escaped into the future, to dwell within the forms of beetles that shall inherit the earth when mankind is dust.

In later years Peaslee received word of strange excavations in the Australian desert that mirrored the visions of his dreams. With Wingate beside him, he crossed that barren waste and beheld the blackened ruins of the Yithian city. Down into the labyrinth he descended, recognizing the titanic halls and shadowed passages of his long-lost captivity. The trapdoors that had once confined the polyps now yawned open, and in the depths he found a metal case that confirmed his every memory. Yet when a clamor of his own making echoed through those ancient corridors, a stirring answered from below. In terror he fled, abandoning the case and the proof it contained.

When dawn came, the desert had swallowed the ruins. No trace of the city or the horrors beneath remained. Peaslee returned home, burdened by the final, ineffable truth, for within the lost case had rested a book written entirely in his own hand—a relic not of his past, but of another age, and another body, beneath the monstrous sun of a forgotten world.

S. T. Joshi has observed that the spectral beauty of the 1933 film Berkeley Square awakened in Lovecraft a strange recognition of self, shaping the conception of “The Shadow Out of Time”. The author beheld the picture four times, entranced by its vision of a man whose spirit drifts backward to mingle with that of an ancestor long dead. To Lovecraft, it seemed “the most weirdly perfect embodiment of my own moods and pseudo-memories,” a work that spoke to his lifelong sense of existing out of time, as though his true consciousness belonged to an earlier century. Yet the film’s handling of temporal exchange left him dissatisfied, and in his novella he sought to perfect what the cinema had only dimly perceived.

Other influences whispered through his imagination: H. B. Drake’s The Shadowy Thing, Henri Beraud’s Lazarus, and Walter de la Mare’s The Return, each touching upon the dread mystery of mind and body undone. Critics would later call the tale his summit of achievement. Lin Carter saw in it a grandeur of time and cosmos unmatched in his other works, while Martin Andersson named it his magnum opus, the true measure of Lovecraft’s cosmic vision. Yet the author himself regarded the story with cold detachment, sending the single manuscript to August Derleth without retaining a copy, as though weary of his own creation.

In later years, new voices would awaken its reputation. Cinescape placed it among the finest works of speculative art, and Publishers Weekly hailed its return to print. Scholars Edward Guimont and Horace A. Smith have discerned within it, and within At the Mountains of Madness, the birth of that haunting archetype of science fiction: the vast, incomprehensible structure whose very silence proclaims the smallness of man before the infinite.

“The Haunter of the Dark”

In the city of Providence, beneath the brooding shadow of Federal Hill, there stood a church long abandoned to dust and dread. Robert Blake, a young writer steeped in occult studies, felt an unwholesome fascination for that decaying edifice, once the lair of the accursed Church of Starry Wisdom. The foreign folk of the hill whispered of monstrous rites and a presence older than mankind, yet their warnings only deepened his curiosity.

Within the darkened nave, Blake discovered the mouldering skeleton of the lost reporter Edwin Lillibridge, and upon a pedestal of alien workmanship, a strange crystal of unearthly sheen known as the Shining Trapezohedron. The stone pulsed with an inner life, its depths shifting like a window into the gulfs between the stars. In touching it, Blake awakened that which no mortal should stir, and fled into the night, haunted by the sense that eyes beyond time had turned upon him.

The horror imprisoned in the church could stir only in darkness, restrained by the ceaseless lights of the city. Yet when thunder rolled and the storm broke, the power faltered and prayers rose from terrified throats. Blake, in his high room, pleaded for the light to endure, but the lamps flickered and went out. What came then was not of this earth. When dawn returned, he was found lifeless before his window, his face twisted in unspeakable fear, and his dying words spoke of black wings and the burning eye that sees all worlds. Later, a trembling doctor cast the blighted stone into the waters of Narragansett Bay, though none can say if the thing it summoned sleeps once more or waits beneath the depths for the turning of the next dark age.

Lovecraft conceived “The Haunter of the Dark” in response to Robert Bloch’s “The Shambler from the Stars”, in which a writer much like Lovecraft perishes by forces he cannot name. With grim mirth, Lovecraft answered by crafting the fate of Robert Harrison Blake, a figure molded in Bloch’s likeness, whose curiosity drew him into the shadows of an ancient church. Years later, Bloch would close their dark correspondence with “The Shadow from the Steeple”, binding the three tales in a cycle of mutual dread.

Some threads of the story reach back to Hanns Heinz Ewers’ “The Spider”, a tale of unseen horror and mounting fascination that Lovecraft had studied with care. In Blake’s final writings, he invokes the specter of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Fall of the House of Usher”, for like that haunted trinity of brother, sister, and house, Blake, the church, and the spectral Haunter seem bound by a single, corrupted soul. Scholars have read the climax as the moment when the avatar of Nyarlathotep merges with Blake’s mind and is struck by lightning, annihilating both mortal and immortal essence in a single flash of blasphemous light.

Fritz Leiber called it among Lovecraft’s finest and final creations, and R. S. Hadji placed it among the most terrifying works ever to issue from a human pen, for in it one feels the last tremor of a mind gazing too long into the gulf that lies beyond the stars.

HAPPY HALLOWEEN from KEITH and JOE from THE CREATURE DOUBLE FEATURE SHOW! 🎃 👻

This day, my colleagues and I shall partake in a curious masquerade, an act of homage, perhaps tinged with the faintest echo of sympathetic magic. In honor of our esteemed compatriot D, whose mortal labors shall cease with her retirement come the dawning of 2026, we have resolved to assume her likeness for our office’s Halloween observance. Thus shall we adorn ourselves in black, curling wigs, each lock a mimicry of her own luxuriant tresses, and array our forms in her customary vestments: the crimson polo, the sable jeans, and the black sneakers that have long marked her earthly passage through the sterile corridors of our shared toil.

I admit, this guise is not one I would have chosen willingly, for its familiarity borders upon the uncanny; yet in the shadow of her departure, there is an unspoken reverence in donning another’s semblance, as though we flirt with the boundary between the self and the other.

And so, in this spirit of imitation and impending absence, let us turn our gaze upon today’s dreadful reading, H. P. Lovecraft’s “The Book.”

“The Book” is a fragment born in the twilight of H. P. Lovecraft’s creative years, written in the waning months of 1933 and brought to light only after his passing in the pages of Leaves. Within its few surviving lines, a nameless seeker receives from a furtive bookseller a volume of ancient and baleful aspect. Upon studying its cryptic pages, he awakens forces that slumbered beyond mortal reckoning, and the shadow of an unseen presence begins to stir.

In a letter from that same year, Lovecraft lamented a paralysis of the imagination and spoke of countless experiments destroyed in dissatisfaction. Scholars whisper that “The Book” escaped the pyre of his self-judgment, perhaps serving as his attempt to transmute the verse of Fungi from Yuggoth into the darker music of prose, mirroring its first three sonnets.

Years later, Martin S. Warnes sought to complete the fragment beneath the title “The Black Tome of Alsophocus”, in which the dread messenger Nyarlathotep takes possession of a doomed soul. This vision returned to mortal sight in a short film of 2019, later shown at the 2020 H. P. Lovecraft Film Festival and preserved among its Best of 2020 collection, where the echo of that blasphemous tome still seems to whisper through the reel’s faint crackle and shadowed light.